World leaders surely breathed a sigh of relief late this week when President Donald Trump said the United States wouldn’t have to “take” Greenland after all, having been granted permission to establish more military bases instead.

Greenland, being mostly covered in ice, might not seem like an obvious target for Trump, other than its relative proximity to the U.S. on a map. He’s said controlling the Danish territory, which is 90 percent Inuit and a model of Indigenous self-governance, is essential for national security. But even though the president has insisted that climate change is a “hoax,” security experts said, warming temperatures have actually made the island nation more desirable from a geopolitical standpoint.

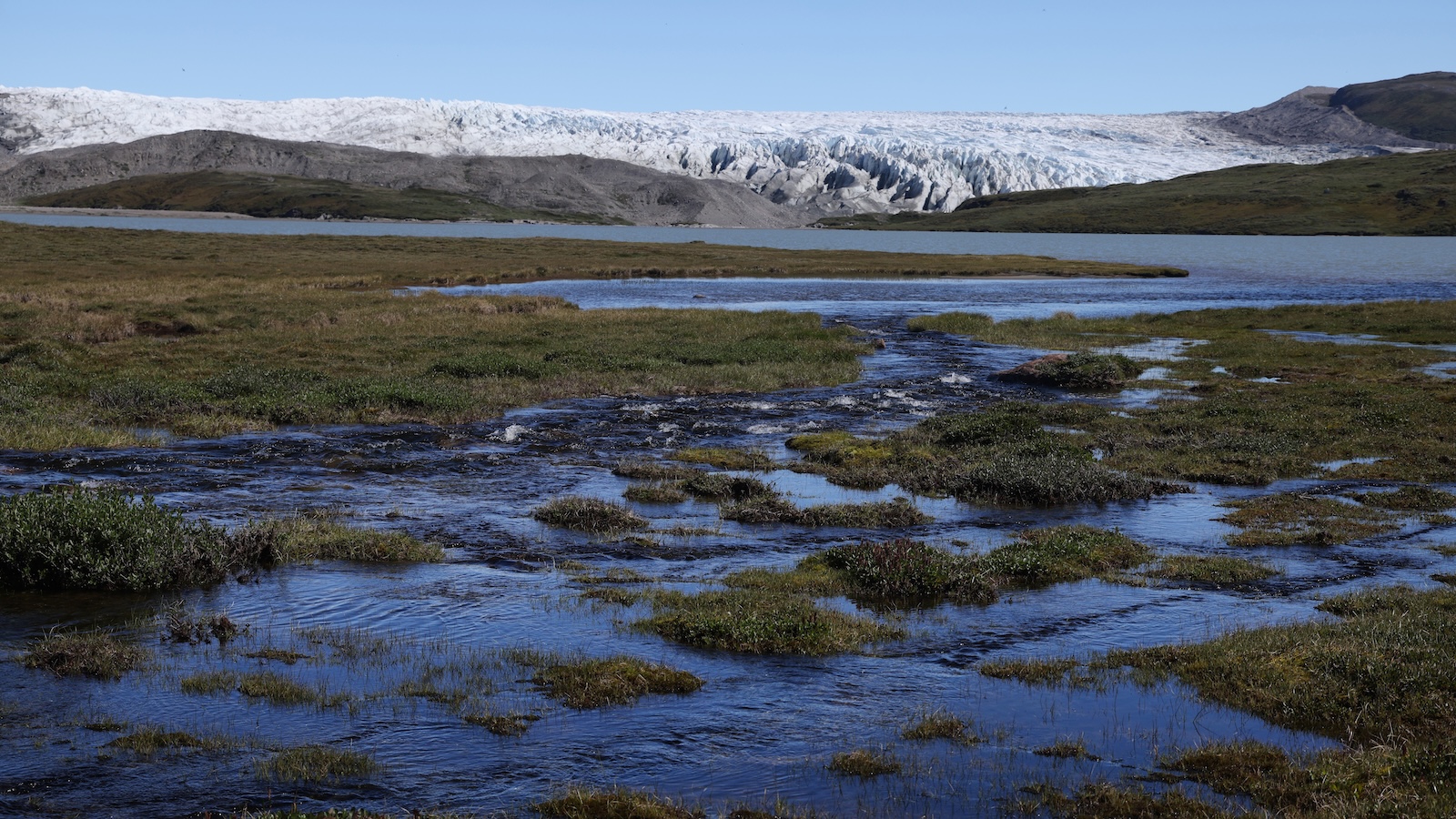

Melting ice sheets open up land and sea that were previously inaccessible, presenting new — albeit dangerous — opportunities. (Never mind that as Greenland’s meltwater flows into the ocean, it could raise sea levels by up to 10.6 inches by the end of this century.)

“The fact that it’s more accessible has in some ways made it more attractive,” said Sherri Goodman, senior associate at Harvard Kennedy School’s Arctic Initiative and the author of the 2024 book Threat Multiplier: Climate, Military Leadership, and the Fight for Global Security.

Take the new shipping routes that have emerged as Arctic sea ice retreats. Already, Russian and Chinese ice breakers have begun traversing what’s called the Northern Sea Route along Russia’s coastline. It connects ports in Asia to those in Europe, and is much shorter than sailing through the Suez Canal. This polar route could cut shipping times by nearly 40 percent and costs by more than 20 percent. In October, Russia and China signed an agreement to develop the route, sometimes referred to as the “Polar Silk Road.”

If fossil fuel emissions continue as expected, most of the Arctic Ocean could be free of summer sea ice by 2050, reshaping global trade. “I think it’s actually moving faster than we even predicted,” Goodman said. Warming temperatures could create another route, called the Northwest Passage, that skirts Greenland’s coastal waters — which may be of interest to the U.S. That region could become navigable to the average tanker within a few decades. However, as the island’s ice deteriorates, more icebergs could litter these waterways, creating hazards for ships.

That could further complicate the already tricky economics of Greenland’s rich mineral resources. Geological surveys suggest that the island is loaded with a slew of rare earth elements like the praseodymium used in batteries, the terbium that goes into screens, and even the neodymium that makes your phone vibrate. Perhaps most importantly for the Trump administration, these minerals are essential for defense purposes, including weapons and navigation systems.

“They sit at the heart of pretty much every electric vehicle, cruise missile, advanced magnet,” Adam Lajeunesse, a public policy expert at Canada’s St. Francis Xavier University, told Grist last year. “All of these different minerals are absolutely required to build almost everything that we do in our high-tech environment.”

But Greenland hasn’t been mined extensively for good reason: It’s difficult — and expensive — to work there. Even though companies can already dig along the ice-free southern coastlines, the massive amount of ice that covers the island makes it logistically difficult to keep operations going — there’s no railroad, for example, to transport materials. Brutal weather, too, can shutter an airport for days, making it impossible to fly in essential supplies. And the way that rare earth elements are distributed within the ground makes retrieving them especially laborious — for every ton of minerals an operation digs up, it produces 2,000 tons of toxic waste.

Greenland’s ice is in serious trouble in part because of a phenomenon called Arctic amplification. As ice in the far north disappears, it exposes more ocean and land, which is darker and absorbs more of the sun’s energy. This creates a feedback loop in which warming begets more warming. Accordingly, the Arctic is heating four times faster than the rest of the planet.

Yes, as climate change destroys ever greater expanses of Greenland’s ice, more land will become accessible to mine. But it also will compound the logistical challenges: Frozen ground, known as permafrost, can thaw and destabilize roads and other infrastructure. Hillsides held together by ice can collapse as melting continues in the decades ahead. (When the weight of ice disappears from the island, the land will also dramatically rebound — think of it like removing a bowling ball from a memory foam mattress.) And if you’re mining on land next to a melting glacier, it’s not producing a gentle trickle of water, but a torrent of liquid and boulders.

“This is an unstable environment,” said Paul Bierman, a geoscientist at the University of Vermont and author of the book When the Ice Is Gone: What a Greenland Ice Core Reveals About Earth’s Tumultuous History and Perilous Future. “If you’re a business, and you’re thinking about sinking tens of millions of dollars into a new port to remove the ore, or to build roads across this permafrost terrain to transport ore with large trucks, that becomes a risk and an expense.”

Mining operations could even accelerate the decline of the sheet, due to polluting dust darkening the ice. “I would argue that mining is getting more difficult, not easier, as climate changes,” Bierman said. “I think the current administration’s focus on economic resources in Greenland is horribly misplaced.”