Back in 2006, when George W. Bush was president and the Paris Agreement was still a decade away, the city of Tucson, Arizona, made a modest plan to do something about climate change. It set a goal to reduce city-wide greenhouse gas emissions 7 percent below 1990 levels, and gave itself a generous 14 years to do it.

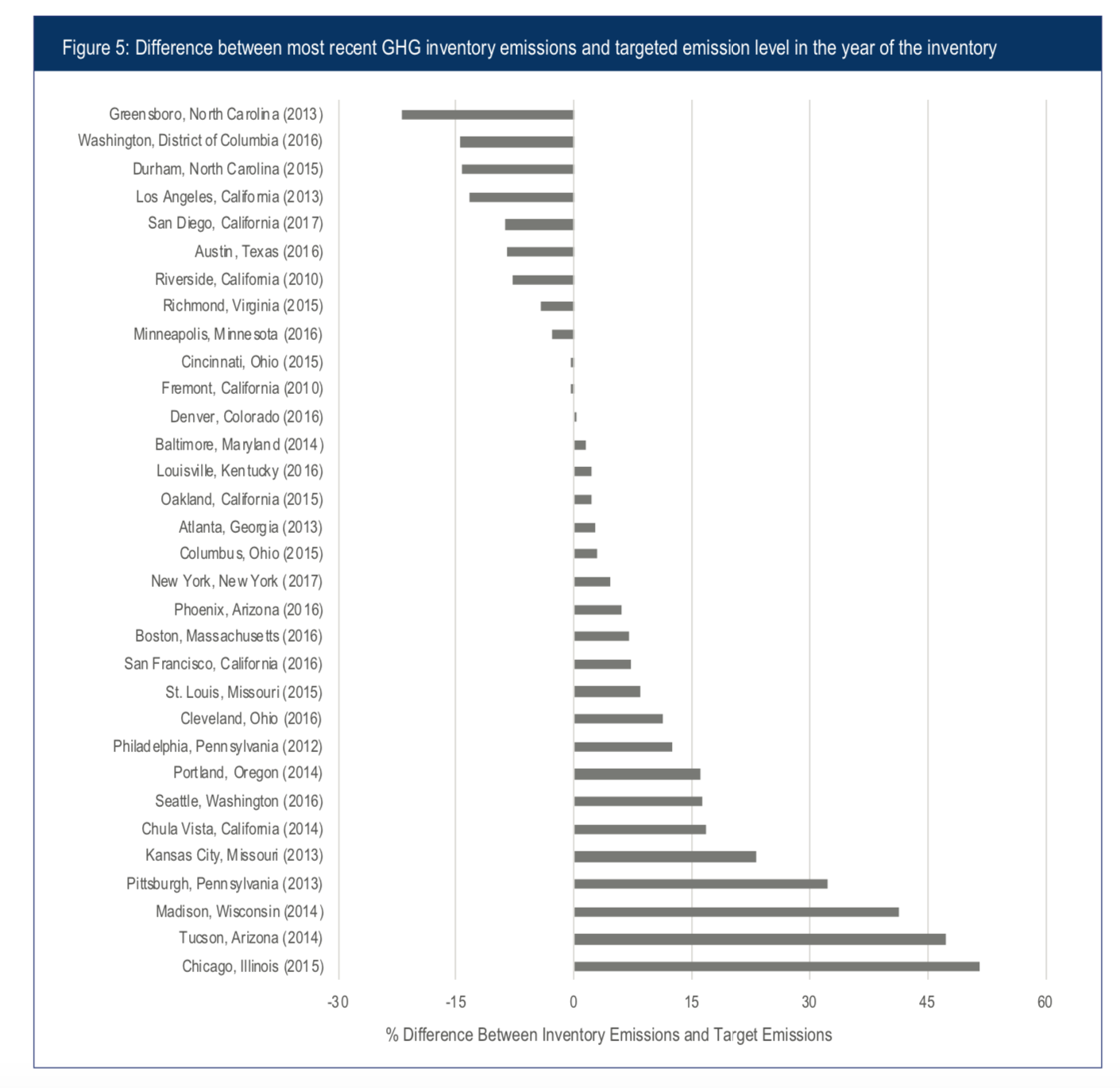

As the deadline approaches, Tucson’s odds for success do not look good. The most recent inventory of the city’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions only goes through 2017, but by the end of that year, emissions had risen about 26 percent higher than 1990 levels amid sprawling growth. Meanwhile, Tucson has also become the third-fastest warming city in the country.

Tucson’s climate flop is not an outlier. A report released on Thursday by the Brookings Institute, a non-partisan public policy think tank, analyzed climate action in the 100 largest cities in the U.S. and found that less than half of them have made plans to reduce their emissions. Out of those that have, only about 15, or one-third, are on track to meet their targets.

“It is very much a mixed bag,” said Mark Muro, a senior fellow at Brookings and one of the authors of the report.

Local climate action has been a beacon of hope as a flood of environmental rollbacks and climate denial rushed out of Washington over the past four years. When Donald Trump took office in 2017 and announced he would pull the U.S. out of the Paris Agreement, cities around the country vowed to “stay in.” Seventeen of the largest 100 cities either made new climate plans or updated previous ones, according to the study.

But even if all of the cities with climate targets pulled them off, they would only achieve about 7 percent of the emissions cuts the U.S. promised to make as part of the Paris Agreement. Without federal incentives to spur widespread action, this bottom-up approach was never going to cut it.

Notes: The numbers in parentheses next to the city name represent the year of the most recent GHG inventory. Positive values mean that the emissions from the city were higher than the targeted emissions for that year. Brookings Institute

The study notes that there’s a limit to what cities can achieve on their own without regional or state cooperation and incentives. For example, power generation is a huge part of any city’s carbon footprint, but it’s typically regulated at the state level. Some cities also don’t have the authority to develop building codes or other local laws that are stricter than state requirements.

“To the extent that we’re relying entirely on the resistance of cities, we may be expecting too much,” said Muro.

Cities are also struggling to produce regular greenhouse gas reports. Among the 45 cities that established a baseline inventory of their emissions, follow-up measurements were sparse. An additional 22 cities announced intentions to develop a climate action plan, but had not even measured their baseline emissions. Conducting an annual greenhouse gas assessment is challenging and time consuming, but as the saying goes, you can’t manage what you can’t measure. Moving forward, the report suggests, cities need to figure out ways to streamline or automate their emissions inventory process.

Though the overwhelming finding of the study is that local climate action is underwhelming, there were a few silver linings. For one, about 40 million people, or 12 percent of the U.S. population, live in bigger cities that have “active and fully-formed climate action plans,” according to the report.

There is a strong concentration of local climate action in California, which was not surprising to Muro. Los Angeles has been one of the most successful cities in reducing its emissions, albeit largely due to the conversion of coal-fired power plants to natural gas. But Muro said he was encouraged to see that outside of California, climate plans were pretty evenly spread out across the country, and were particularly strong in some unexpected places. “Durham, Cincinnati, Richmond,” he said. “Those are not necessarily the typical cities you think of when you think of climate innovation, but all of them look quite good by our measurements.”

Climate action is ramping up quickly, and not everything that’s happened made it into the report. Just last month, Tucson declared a climate emergency and announced it would make a new plan to become carbon-neutral by 2030. Earlier this year, the cities of Miami and Columbus, Ohio, which both had 2020 emissions targets, upped their ambitions to carbon-neutral by 2050. Miami also released a new greenhouse gas inventory for 2018 and found that it surpassed its initial target two years early.

The report concludes that “ultimately, a few dozen vanguard cities alone cannot be the primary mechanism by which GHG mitigation efforts are implemented.” But even if Joe Biden, who has an ambitious federal climate plan, wins the presidential election, the role of cities won’t go away. New initiatives at the federal level “should be supportive of cities and build in space for their experimentation and their action,” said Muro. “We need to help unleash it.”