Like many of us, Evan Stephens Hall spent most of 2020 alone in his apartment. His band, the indie rock outfit Pinegrove, was supposed to be touring its new album across Europe and the U.S. But instead Hall was stuck at home, consuming the news, and trying to process a world that seemed like it was falling apart in fast-forward. So he began to metabolize the wild events of the year the only way he knew how — through music.

He said his idea for an album began to take shape when photos started circulating online of blood orange skies blanketing the west coast — the result of sunlight filtered through thick wildfire smoke in September of that year. “It looked like a terrifying sunset but it was 2:30 PM,” Hall said in an interview with Grist. “It was a phenomenon we’ve never seen before.”

The experience inspired “the small action of writing a song:” Orange, the first single off a new 11-track album called 11:11 that was released in full in January. The song doesn’t once use the words “climate change,” but the message embedded in its pithy refrain is clear: Today the sky is orange, Hall sings as the music builds, And you and I know why.

Hall said the lyric has a double meaning. On one hand, it’s filled with sadness and anger over climate inaction. “But then on the other, there is solidarity, I hope, in that phrase,” he said; that “you and I” can find strength in that shared recognition of mass systemic failure.

This balancing act between righteous anger and finding hope in connection is a template for the record as a whole, and for the larger project Hall is now attempting with Pinegrove. Despite spending much of 2020 in isolation, Hall tried to cultivate an ethos of looking outward and seeking solace in movement-building and community. In the past, his songs have wrestled with how one should spend a life, and now he was finding new answers. “I was sort of seduced by this idea of like, the lonely, solitary artist,” he said. “I think I wasted some years thinking that that was the move. But no, it’s way more about meeting your neighbors.”*

Through this new set of songs and the band’s platform, he’s hoping to pass the message on to listeners that getting involved in things like climate activism or local politics can serve as an antidote to these bleak and anxiety-inducing times.

Pinegrove broke out in 2016 with its first full-length album Cardinal. Hall’s sometimes literary, sometimes literal lyrics evoked scenes of post-college meandering and dealt with familiar themes of love, friendship, self-reflection, and art. He packaged his prose in rich, rootsy guitar rock that invited audiences to sing along, attracting a devoted fan base that now frequently drowns out the band at their shows.

On 11:11, Hall doesn’t leave those themes behind, but brings them into conversation with the absurdity, tragedy, and dystopic atmosphere that has defined the 2020s thus far. His references tend to be more evocative than overt — the “awful feeling something’s off,” birds singing “dissident tunes.” But at times he delivers scathing social commentary, with lines about a do-nothing politician who acts like a celebrity, an anti-masker in a “never forget” t-shirt, images of a society in decline, and the “riddle of empathy” in it all.

Pinegrove has always offered fans more than just its music. Obsessed with symbolism, Hall created a lexicon of sorts to go along with each album — colors, shapes, and other motifs with multiple meanings that show up in songs, on album art and merch, and that Hall and some of his fans, many of whom call themselves ‘Pinenuts,’ have tattooed onto their bodies.

The numbers “11:11” are the latest addition. A few of the many explanations for the title: A visual allusion to a stand of trees (a pinegrove, if you will); a reference to the old adage to make a wish when you catch the clock at that time (“my attempt to wish a better world into existence,” Hall told me earnestly); an ode to patterns. He said that in writing the album he also became interested in the palindrome as a metaphor for “getting caught in this loop of history where the problems just seem to get worse and we’re not trying any new ideas.”

It’s a phenomenon that’s both mirrored and magnified, he said, by “these addictive behaviors like just being on your phone, scrolling the night away.” But even though that experience of “doom-scrolling” was very much on his mind while working on the album, the songs feel refreshingly absent of anything approximating that experience. Where many contemporary writers have mined the experience of being Very Online for portrayals of modern anxiety, Hall ran in the other direction. His lyrics are mostly focused on the world around him, often on nature itself — in the forest, on the beach, looking up at the sky. He said he was inspired by the way the poet and author Ocean Vuong has talked about his work.

“He describes wanting to acknowledge and interrogate violence without making something that is itself violent,” Hall explained. “I think that that line ran through my head a few times as I was composing an album that’s really about, in some ways, ecological and social violence — but wanting ultimately to make something that felt comforting to people, that somebody could turn to in a time of distress.”

Hall hopes the songs help listeners emerge from those feelings and feel more confident, perhaps even motivated to take action. Outside of his music, Hall has used Pinegrove’s platform to prod fans into turning to activism or politics as a salve for despair. The band has let organizations like the Democratic Socialists of America and the Sunrise Movement table at their shows. They’ve also promoted presidential candidate Bernie Sanders on Instagram and brought progressive candidates running in local elections on stage at shows.

The day before 11:11 was released, the band promoted these groups, as well as New York State Assembly candidate Sarahana Shrestha, on Instagram, writing: “It’s so easy to feel defeated and despondent about it all — who doesn’t! — but let us humbly suggest that in those moments, perhaps you might turn to any of these groups for some concrete ways to get involved.”*

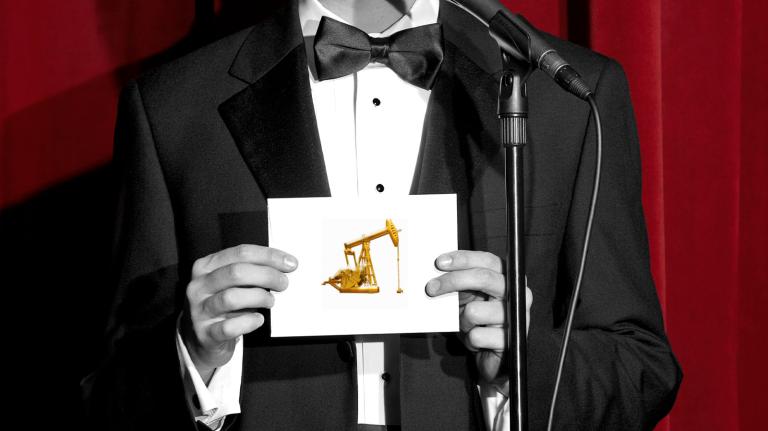

Climate action — or really any political action — in the music industry has long taken the form of fundraising, with benefit concerts and pledges to donate a portion of tour revenue to a cause. More recently, bands have begun to advertise efforts to reduce their carbon footprint, whether by refusing single-use plastics or buying carbon offsets. But it’s rare for a musician to use their platform to critique the larger social systems that keep us hooked on plastics and fossil fuels, or encourage fans to get involved in changing them.

The suggestion to get involved isn’t superficial — Hall said he started organizing with the Democratic Socialists of America in his area during the pandemic, doing phone banking and knocking on doors. He ended up meeting all kinds of people who felt like they had no one to talk to. “Of course, there’s some people that don’t want you at their doorstep, but I’ve made some really incredible connections with people and that has made me feel less atomized, isolated, lonely, and more of a national and global citizen,” he said.

Hall doesn’t know the extent to which fans are actually engaging with the band’s more political message. But he said his hope was to initiate conversations and to help people discover opportunities for action that they may have been hesitant to seek out. “There may be some people who don’t feel so comfortable with it, and I hope at the very least they might interrogate that discomfort a little bit.”

The new album closes out with a track called “11th Hour,” which, in a way, evokes Don’t Look Up, the star-studded Netflix satire about an asteroid about to hit the earth. In the song, Hall is on the phone with a friend, reality is exploding, and he’s laughing but he doesn’t know why. An actual emergency noooowwwww, iiiittt’s really going down, Hall sings toward the end. The music cuts out abruptly after the final word.

Though the song was written long before Hall had seen the movie, he saw the similarities between the two. Both works attempt to describe our devastating and also sort of incomprehensible current reality, all while trying to make it more accessible through humor or melody.

“I’m hoping that there are going to be more and more works of art that figure out an engaging way to tell the story,” he said “and to talk about some of the feelings that we are having around this — anger, terror, love, community, feeling wistful about the beautiful places you’ve been, and the people that you’ve been there with.”

*Correction: An earlier version of this article misquoted Hall’s statement about “meeting your neighbors” and misstated the name of the candidate running for New York State Assembly.