This story is part of the Grist series Parched, an in-depth look at how climate change-fueled drought is reshaping communities, economies, and ecosystems.

Mark Kelly, the incumbent Democratic senator from Arizona, is facing a strong reelection challenge from far-right Republican nominee Blake Masters, in a race that could be key for control of the Senate. Last month, during a televised debate between the two candidates, Masters went on the attack, criticizing Kelly’s positions on several issues.

Toward the end of the debate, after skewering Kelly on inflation and the border, Masters hit him on a more niche issue: federal water cuts on the Colorado River.

“A few weeks ago the federal government cut Arizona’s water allocation 592,000 acre-feet,” Masters began. “For all you water nerds out there, that’s a lot of water. Guess how much water California had to cut? Zero. Guess what Mark Kelly did about it? Nothing.”

The attack was disingenuous — there was nothing Kelly could have done to stop the cuts, since they were negotiated well before he entered the Senate — but a few weeks later, as the election approached, the incumbent senator made a similar plea. In a letter to the Biden administration, Kelly also urged federal officials to curb water deliveries to southern California’s Salton Sea, saying that the Golden State hadn’t done enough to conserve water, and that any delay would lead “only to tougher choices and litigation” between the states.

Much of the western United States has suffered under drought conditions this year, but the impacts have been most acute in the Southwest, which relies heavily on the Colorado River to supply water for cities and farms. So it is no surprise that drought has emerged as a key issue in the region ahead of this week’s midterm elections. Senators and representatives in close races have talked about drought in debates and campaign ads, with vulnerable incumbents like Kelly touting their efforts to fight the extreme weather conditions as evidence that they’re delivering for their constituents.

While issues like inflation and abortion access still top most voters’ priority lists, the Southwest’s water shortage has nevertheless become an important talking point for western politicians as they hit the campaign trail, and could move the needle in ultra-close races like Kelly’s.

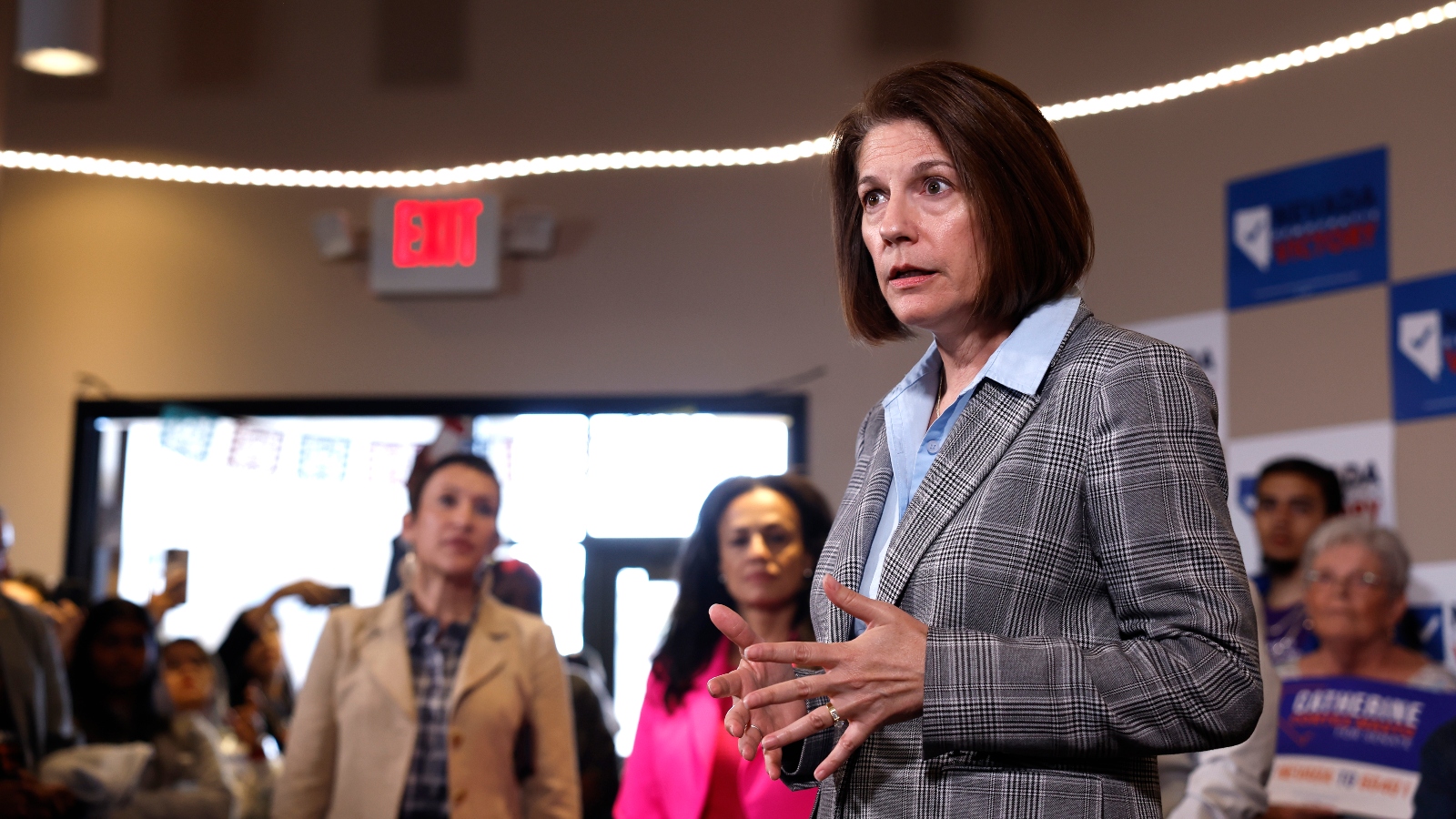

As water levels in the Colorado River continue to fall, the federal government has instituted mandatory water cuts like one Masters alluded to in his debate performance, and users from California to Colorado are scrambling to find new conservation strategies to deal with the coming crunch. In response to the growing crisis, a group of Democratic senators from western states — including Kelly, his Arizona colleague Kyrsten Sinema, Catherine Cortez Masto of Nevada, and Michael Bennet of Colorado — secured $4 billion in drought funding as part of the Inflation Reduction Act, or IRA, which passed the Senate in August. Most of that $4 billion will pay farmers along the Colorado to leave their fields unplanted next year, which will ease the burden on the river. Other funds will go to long-term water conservation strategies, reuse systems, and other drought relief measures.

Three of those four Democratic senators are up for re-election this year, and two of them — Kelly and Nevada’s Cortez Masto — are in serious danger of losing their seats. Arizona’s Kelly is polling just a few points ahead of Masters, who has gained support in recent weeks. Cortez Masto, meanwhile, is in a dead heat with her Republican challenger Adam Laxalt.

Political groups backing Kelly and Cortez Masto have touted their roles in obtaining the $4 billion in drought funding in ads on television and social media, saying it shows how the senators have delivered for their constituents. EDF Action, the political arm of the Environmental Defense Fund, spent $1.5 million on Spanish-language ads hyping Kelly’s drought record.

“It’s easy for politicians to grandstand, it’s harder for elected officials to really be problem solvers,” said David Kieve, the president of EDF Action and a former member of the Biden administration’s White House Council on Environmental Quality. “When they do, their constituents are going to notice and it’s going to be of benefit to them politically.”

Kelly and Cortez Masto have both talked up their drought credentials on the campaign trail in an attempt to show how they’ve delivered for constituents. Cortez Masto, meanwhile, has pushed the Biden administration to enforce tougher and more forward-looking water restrictions, saying the administration needs to ensure that “all states along the Colorado River take the actions that Nevada already has.” The state is relatively well-equipped to withstand the present shortage on the Colorado River thanks to its longstanding policy of banking unused water in Lake Mead, but drought is still front-of-mind for many voters in the state: Almost two-thirds of Nevadans consider dealing with water shortages to be a top priority, according to a recent EDF poll, ranking it higher than education and crime.

But while talk of fighting drought is popular on both sides of the aisle, the topic of climate change is not. To that end, Kelly and Cortez Masto are trying to separate the two issues, said Elizabeth Koebele, a professor of political science at the University of Nevada, Reno who has studied drought politics.

Cortez Masto, for instance, has spent much more time touting the drought investments in the Inflation Reduction Act than she has spent discussing the bill’s new investments in renewable energy. She has also insisted she doesn’t see climate-fueled water shortages as a campaign issue, and has often discussed it without mentioning global warming. That’s in spite of the fact that rising temperatures have helped to make the current western megadrought the worst in more than a millennium.

“Climate is not a priority issue for voters often, and so we’ve actually seen some of these candidates up for reelection in the West who have sort of downplayed talking about climate,” said Koebele. “Anytime drought gets attached to long-term trends in climate, it gets more politicized.”

Drought has popped up in other close congressional races as well. In California’s agriculture-heavy Central Valley, where residents have struggled with dry wells and polluted groundwater for decades, Republican Representative David Valadao has waffled on the relationship between drought and climate change.

“We’ve always had drier years and wetter years,” he told CNN, acknowledging that “there’s a possibility that [climate change] plays a role” in drought. President Biden won Valadao’s district by about 10 points in 2020, which makes Valadao one of the most vulnerable House Republicans this election season. His most prominent opponent, Democrat Rudy Salas, has not emphasized climate change as an issue in itself, but has touted his efforts in the state legislature to secure water infrastructure and support for ailing farmers.

Also in the Central Valley, a Republican farmer named John Duarte is hoping to flip a Democratic-held seat that encompasses the cities of Modesto and Merced. Duarte became famous for engaging in a long legal battle against the federal government over water regulations, and he’s spent a lot of time on the campaign trail talking about the need to build new dams to shore up California’s water supply, something environmental groups have long opposed.

The stakes around all this talk are high. The outcome of the midterms could sway the future of federal drought policy.

The current Democrat-led Congress has passed three major spending bills that all contained some kind of funding for climate action or climate resilience, with money available for drought response in each one of them. In addition to the $4 billion from the Inflation Reduction Act, the group of senators led by Kelly and Sinema also secured more than $8.3 billion in long-term drought funding in last year’s bipartisan infrastructure bill. That money will go to develop new reservoirs and other water sources across the region. Nevada governor Steve Sisolak, meanwhile, has used money from the federal $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan of early 2021, also known as the COVID-19 stimulus bill, to fund water conservation efforts.

If Democrats lose control of one or both chambers, it could imperil future spending like this. The House of Representatives passed a drought spending bill back in July that contained another $500 million for western water conservation, but the bill stalled out in the Senate for lack of Republican support. If the Republicans retake the House or the Senate, that legislation will likely be dead in the water, especially if Kelly and Cortez Masto aren’t around to advocate for it. Republican leaders have said they hope to use their new majorities to cut government spending and investigate President Biden, which takes even more drought funding bills off the table.

Meanwhile, neither Masters in Arizona nor Laxalt in Nevada have put forward any detailed proposals for drought response: both candidates have said they believe building new desalination plants could help increase the West’s water supply, but desalination on a large scale is difficult to achieve. Laxalt has criticized Cortez Masto for supporting funding efforts like the Inflation Reduction Act, saying she “should have demanded real change in exchange for her vote on any number of Democrat spending bills.”

Even so, says Koebele, a change in who controls Congress won’t derail the ongoing negotiations over how to solve the Colorado River crisis. Those negotiations are led not by Congress but by representatives from state water departments, many of whom are longtime civil servants, and by major water users, who aren’t politicians at all. The same goes for issues like the Central Valley’s groundwater shortage — Congress can help out, but it’s up to local leaders to find permanent solutions.

“These water managers are closer than senators and representatives to the actual water issues, so there’s going to be continued momentum,” she said. “Policymaking is still going to happen, but it might change the resources that the federal government can bring to the table.”

*Editor’s note: Environmental Defense Fund is an advertiser with Grist. Advertisers play no role in Grist’s editorial decisions.