We often talk about electric rates as if the only thing that goes into determining them is the power source. In some sense, this is right: If a utility’s power costs go up, and nothing else changes, the price they charge consumers will likely eventually go up.

But, this understanding doesn’t fully appreciate the role of rate design in determining what the rate will be. When utilities — and utility regulators — design an electricity rate, they make numerous decisions that impact the price that consumers will ultimately pay, regardless of power source. Ignoring these other decisions can lead to lazy thinking about rate impacts, which can ultimately lead to poor decision making.

For example, the standard canard is that “renewables make rates go up.” Depending on the particular circumstances of any one utility, it may or may not be true that renewables are more expensive than fossil fuels (although the conventional wisdom that renewables are more expensive is almost certainly overstated). Directly linking this to the final rate impact, though, ignores all of the other things that go into electric rates.

We can look across the ocean to see some examples of how different design decisions impact rates. The European Union has modern electricity markets and their electric power system is similar to the United States’ in many ways. But, European households not only pay higher prices for power than the United States, but the prices vary dramatically across Europe. This is not just because they have different generation profiles (although this may play a role), but is also because they have different rate designs.

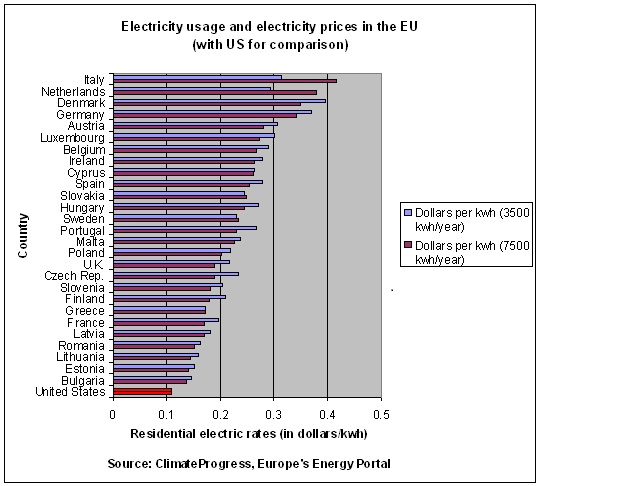

Here’s a chart showing the rates that residential consumers pay for electricity in Europe and the United States. The chart shows the rate that a consumer pays if they use either 3,500 or 7,500 kilowatt-hours of electricity per year. The European rates were converted into dollars using a 1.5 USD to 1 EUR exchange rate. (For comparison’s sake, I’ve included the United States, where the average consumer uses over 11,000 kilowatt-hours per year. This data is not differentiated by consumption level.)

There are at least two interesting things here. First, you’ll see that every country has higher rates than the average residential rate in the United States. Second, you’ll see that in some countries, rates go down as you use more power, but in other countries, the rates actually go up as you use more power. Since the simplest electric rates are made up of a fixed charge (to cover the fixed costs of the power system) and a per-kilowatt-hour charge (to cover the variable cost of generating power), it makes sense that average rates would decline with higher usage (because the fixed costs are spread over more kilowatt-hours). This is the case in most places in Europe. But in Italy, the Netherlands, Slovakia, Sweden, and Greece, bigger users pay more for power, which is an indication that they have a rate system that encourages efficiency. This is a choice that they’ve made, and a rate impact that is unrelated to their generation source.

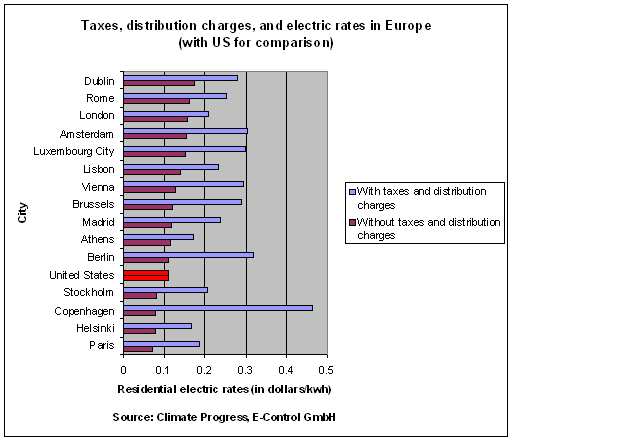

Then, we also can look at data about how electric rates in various European cities [PDF] are driven by taxes and distribution charges; that is, the things that aren’t strictly driven by power generation. (Again, I’ve included the United States for comparison’s sake, but I only have data for the rate with all of the charges, not just power.)

Here we see just how much taxes and distribution charges drive rates. A consumer in Copenhagen, for instance, pays more than 40 cents per kilowatt-hour for electricity, but less than 10 cents of that is related to actually generating power. In London the effect is much smaller. So, even though London’s power is more expensive, their consumers pay lower overall rates. This is another example of a rate impact that is unrelated to the generation source.

We should be skeptical when anyone attributes their electric rates to the type of power they use. And, we should be just as skeptical when someone tells us that our rates will necessarily go up because of the type of generation we use, ignoring all of the other choices that utility executives, elected officials, and regulators make in determining a rate.

Note: This post builds off of a column last week that compared electric rates around the world. Regrettably, some of the data from that column contained errors, as several commenters pointed out. Most problematic, some of the data points were based on published tariffs and were not comparable to each other. While these errors do not negate my basic argument, I apologize for the mistakes and confusion, and appreciate the feedback.