Cross-posted from Climate Progress.

The political reaction to the Solyndra scandal has been laughably devoid of both short-term and long-term historical perspective. In an attempt to exploit a political opportunity, many House Republicans are railing against government investments in the renewable energy sector. However, those same politicians requested millions of dollars for cleantech projects in their own states just a year or two before.

This bad case of amnesia stretches far beyond the last two years. Apparently, many in Congress have forgotten about the last 100 years of government investments in oil, gas, and nuclear — all of which have far outpaced investments in renewable energy like solar photovoltaics, solar thermal, geothermal, and wind.

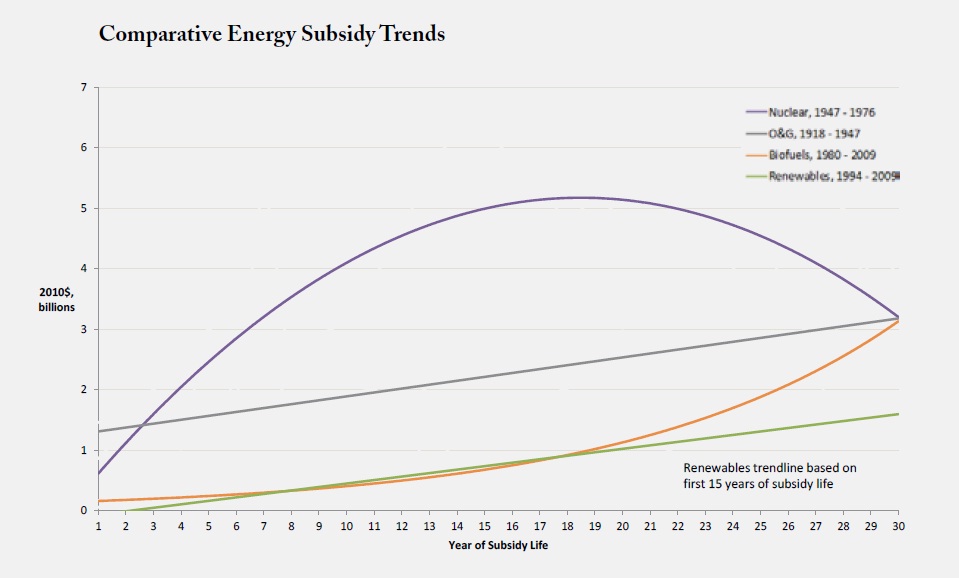

A new study [PDF] with terrific charts, released by the venture capital firm DBL Investors, attempts to quantify and contrast those government investments. The researchers looked at the vast array of federal incentives — tax credits, land grants, tariffs, R&D, and direct investments — and found that renewables have received far less support than any other sector:

As a percentage of inflation-adjusted federal spending, nuclear subsidies accounted for more than 1 percent of the federal budget over their first 15 years, and oil and gas subsidies made up half a percent of the total budget, while renewables have constituted only about a tenth of a percent.

The researchers are somewhat selective about which subsidies they factor in. In order to come to directly comparable figures, they outline four criteria for evaluating subsidies: The subsidy is designed to increase production of the targeted resource; all the data for the subsidy is available; the subsidy existed during the early stages of of domestic production; the inclusion of the subsidy allows for meaningful comparison across different sectors.

When adding them all up over time, the report’s authors found that on an average yearly basis, renewables represent a small fraction of the the total government investments in the energy sector. Here are two great charts that make that clear:

Note: The above chart is average annual support. The cumulative spending numbers are thus even more disparate:

I have some issues with this report, however. Firstly, the authors stop tracking the numbers in 2009, and leave out the billions invested through the stimulus package. They claim to do this because of the temporary nature of the stimulus package. While it’s true that many of those programs are already phased out or will be gone by next year, the stimulus is still a very important piece of early-stage investments in the sector. Why leave it out?

The researchers also neglect to include the short burst of federal renewable energy investment in the late 1970s. While those tax credits and R&D programs lasted only a short while, they still contribute to the overall figures.

Finally, in an attempt to make clear distinctions between the renewable fuel and electricity sectors, the report separates biofuels from the renewables category (wind, solar, geothermal). That separation also changes the numbers and makes the renewables subsidy figures much lower than they otherwise would be.

With that said, even if you threw all these other investments together, the subsidies for fossil resources and nuclear would far surpass anything in renewable energy. According to the report, the American oil, gas, and nuclear industries have cumulatively taken in more than $630 billion, with most of those government subsidies created in the earliest days of those sectors in order to build them up.

By comparison, renewables and biofuels together have seen about $40 billion in investment. Add in the stimulus package — $7 billion for the grant program and advanced manufacturing tax credits, and $2.5 billion in credit subsidy costs for the loan guarantee program — and the investment figures still don’t come close to fossil and nuclear investments.

Given the amount we’ve invested in emerging energy industries, the authors explain that today’s renewable energy investments are relatively small compared with other government-led transitions:

Today, as we seek to move towards a more independent and clean energy future, the truth is that renewables — from a historical perspective — are if anything under-subsidized. This weak support is inconsistent with our nation’s own historical energy narrative, which suggests:

Today’s market for cheap power results in part from substantial investment by the federal government in innovative technology.

It takes a substantial amount of money, invested over several years, to bring an electricity generation technology to maturity.

Although energy subsidies can and do serve many policy purposes, the most basic relate to furthering the development and commercialization of technologies deemed to be in the public interest.

Before we start criticizing government investments in emerging energy technologies like it’s some sort of new phenomenon, maybe we need to give ourselves a little history lesson.