The Biden administration has aimed high when it comes to the nation’s clean energy buildout, but a string of setbacks has slowed momentum. Auctions for offshore wind projects have ended in failure and massive carbon storage projects have been canceled, all despite massive subsidies and tax credits from the Inflation Reduction Act. Companies in turn have blamed high construction and shipping costs, high interest rates, and in particular, a lack of transmission availability.

But as some offshore goals falter, the administration is focusing on alternative energy buildout onshore, on its sprawling public lands in the West.

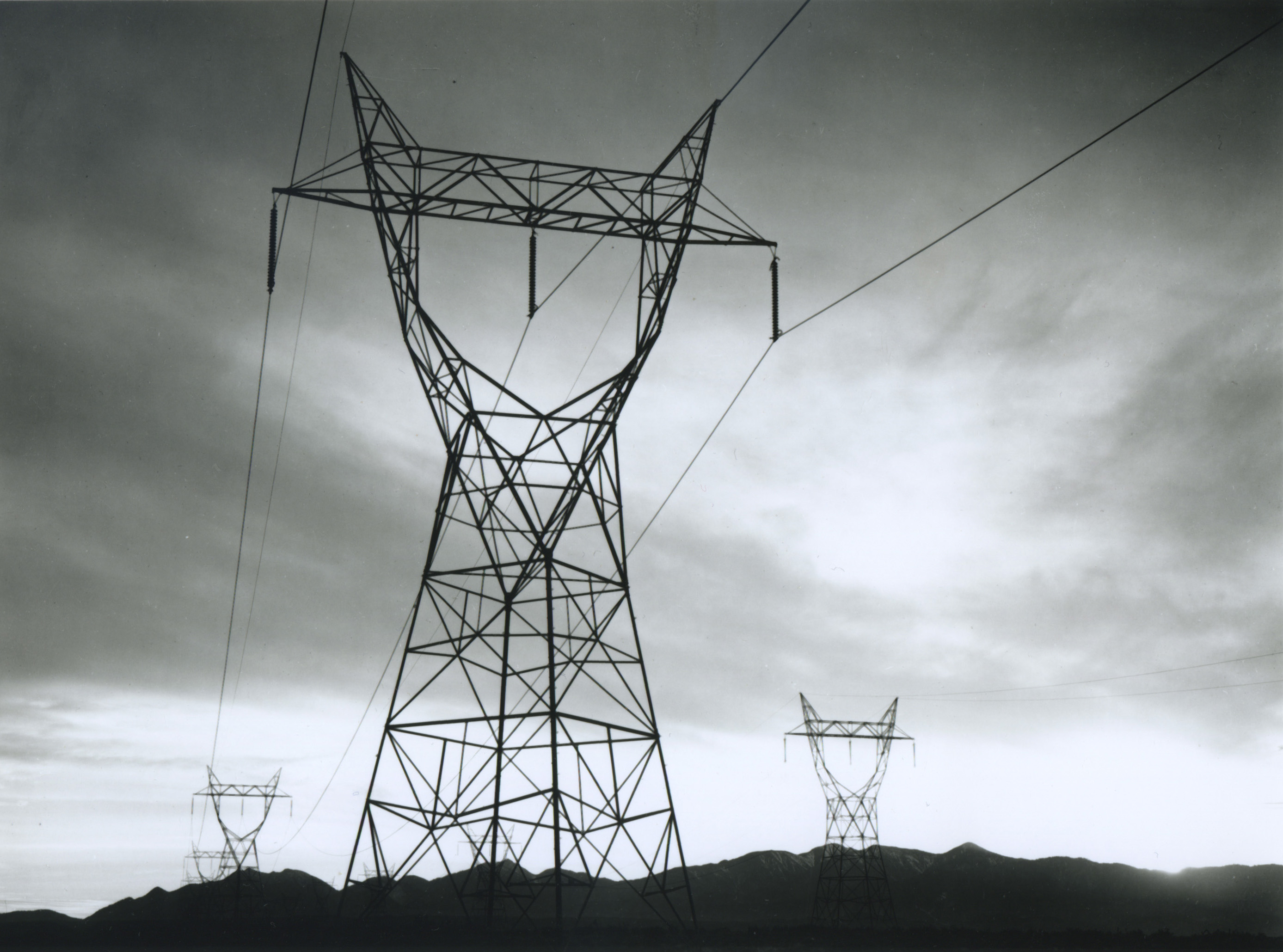

Today, the Department of the Interior announced an additional 15 projects to its portfolio of clean energy initiatives, raising the number of approved projects on public lands to 46 since 2021. These latest are scattered throughout Nevada, Wyoming, Arizona, Utah, and Southern California, making for a total of 16 solar and 10 geothermal projects that will be bolstered by 20 new transmission lines, indicating an interest in solving a major clean energy problem — that is, the issue of how to get all the energy generated in remote areas out to the cities that need it. The new transmission lines will bring electricity across the vast deserts and mountains to the region’s widely dispersed population centers, just as energy costs have skyrocketed.

It’s an attempt to move forward on what’s been called one of the biggest roadblocks to the administration’s hoped-for clean energy buildout. At the end of October, the Department of Energy published the National Transmission Needs Study, a report that analyzed the nation’s energy grid capacity through the year 2040. The study found that between climate change impacts and a surge in electric vehicles and alternative energy sources, the grid would need a massive increase in the nation’s capacity to get electricity from one place to the other, with particular growth needed in the Southeast and Mountain West. In its estimation of both a high energy load and a high clean-energy-adoption scenario, the study estimated that the nation’s grid would need to grow by one and a half times its current size and capacity. There is currently no central grid-planning authority in the United States, so the problem of regulating that growth could get chaotic, dependent on states’ and utilities’ goodwill and commitment to bringing clean energy to the local level.

Despite record investments in clean power, installations actually declined in 2022 for the first time in five years, mainly because lack of interconnection and grid capacity left projects piling up on a backlog of a system that was designed for large, centralized fossil fuel plants rather than many smaller and geographically distributed clean energy projects. In an attempt to circumvent this, the administration is also pushing for action on permitting reform to pass through Congress, which officials say would speed up the approval and construction of projects, and keep the private sector from passing up on opportunities to invest in decarbonization.

“We’ve seen the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission take action on its own motion to improve interconnection processes,” a senior administration official said on a press call. “But that doesn’t take the opportunity away from Congress to help us move even faster in the direction of building outlines that will reduce consumer costs and boost resilience on the grid.”

Some environmentalists have opposed permitting reform or called for better development planning, citing the massive amount of land needed for solar and wind power in particular, and the damage that they can do to fragile ecosystems, particularly in the desert. To that end, environmental impact statements are currently in draft form, with opportunities for public comment on several projects opening soon.