Hawai’i shuttered its last remaining coal-fired power plant last week, bidding farewell to a carbon-intensive energy source that the island chain has relied on for more than 150 years.

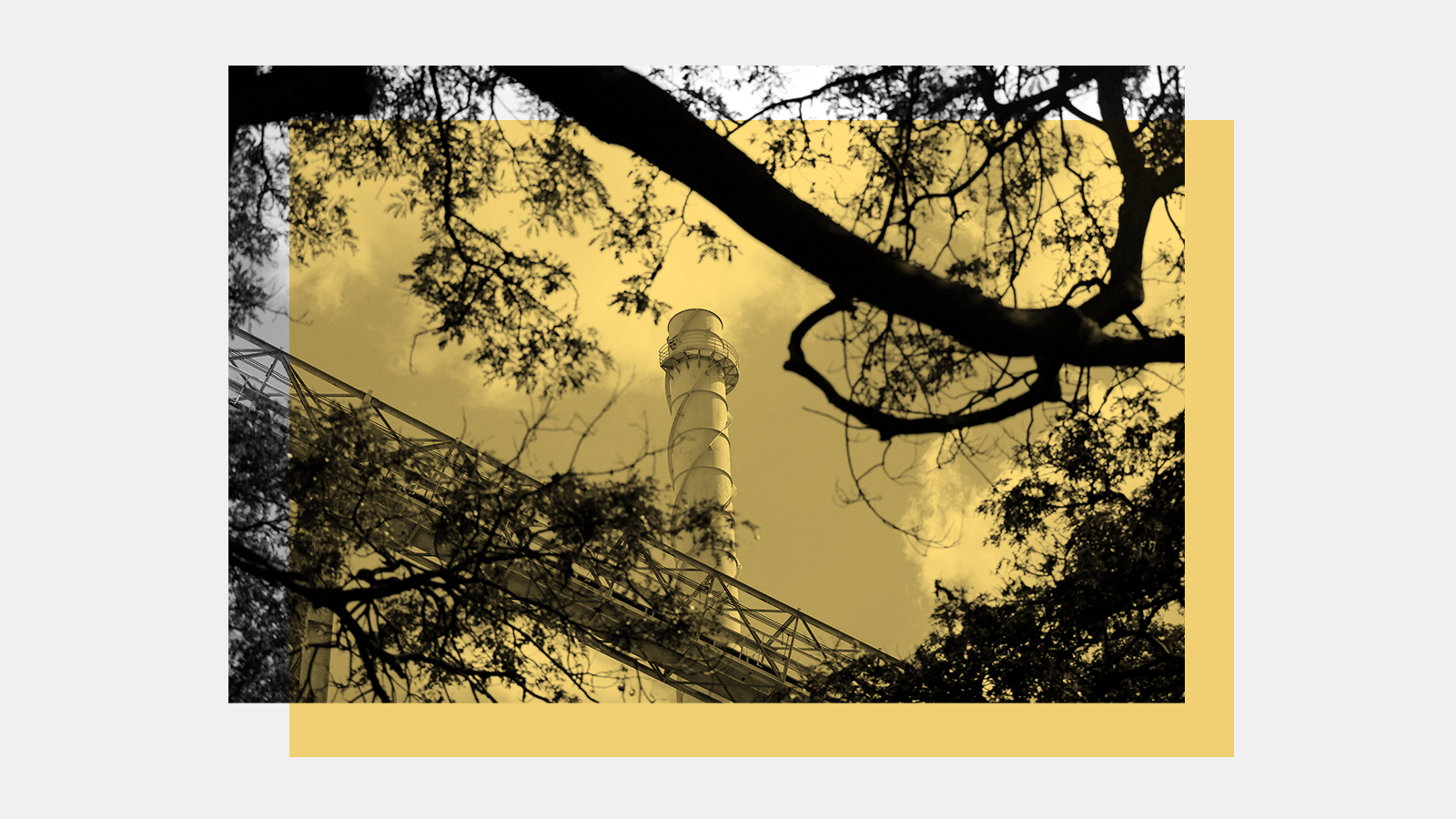

The now-retired power plant, owned by the power generation company AES, had been operating since 1992 on the island of Oahu, home to the state capital of Honolulu. It provided up to 20 percent of the Oahu’s electricity and also emitted some 1.5 million metric tons of carbon dioxide each year.

“Today marks a major milestone in Hawai’i’s clean energy transition,” Scott Glenn, Hawai’i’s chief energy officer, said in a statement.

Hawai’ian policymakers approved legislation in 2020 to phase out coal-fired power generation by the end of 2022, coinciding with the end of a 30-year contract for the AES Hawai’i coal plant in Oahu. That legislation built on previous climate commitments, including the nation’s first state law — passed in 2015 — mandating 100 percent renewable electricity generation by 2045. Since then, more than 20 other states and the District of Columbia have followed suit with similar clean-energy pledges.

Cutting coal will also help Hawai’i get to carbon neutrality by 2045, as mandated by a 2018 law. In 2017, the most recent year for which state data is available, Hawai’i produced 20.56 million metric tons of greenhouse gases, roughly 86 percent of which came from the energy sector.

The challenge now is ensuring Hawai’i has enough renewable capacity to keep up with its energy needs. AES, which supports the transition away from coal and has even helped its former coal plant workers find new jobs in renewable energy, says it’s working on six renewable energy projects across the Hawai’ian islands. Statewide, regulators have approved at least nine other solar, battery, or geothermal projects that are set to begin operating by 2024.

One solar and battery project on Oahu, called Mililani I Solar, was completed at the end of July and has been providing up to 39 megawatts of clean energy at peak times — about one-fifth the capacity of the now-retired coal plant. Miliani I also includes 156 megawatt-hours of battery capacity, allowing energy to be stored and deployed at night, when the sun isn’t shining.

Although Hawai’ian renewables are on the rise, state officials say they still can’t provide enough electricity to fully supplant fossil fuels. Hawai’i is the U.S.’s most petroleum-dependent state, and Hawaiian Electric, the state’s largest electricity supplier, predicts that some coal-fired power generation will have to be replaced with oil — at least in the near term. That replacement is expected to cause a 7 percent bump in Hawai’ians’ electricity bills, which are already some of the highest in the country.

In an interview with the Guardian, Glenn called the state’s continued oil reliance “really unfortunate” but stressed that it would only be temporary and that the move away from coal would pay dividends in the longer term. “[P]hasing out fossil fuels in favor of our own renewable resources will provide more cost stability and predictability,” he added in his statement. “[W]e will be more energy independent and show the world that every action counts.”