This story was produced by Floodlight, a nonprofit investigative newsroom focused on climate accountability.

There’s an unspoken promise when an industry moves into any community: We will disrupt your lives, but in exchange we will provide good-paying jobs.

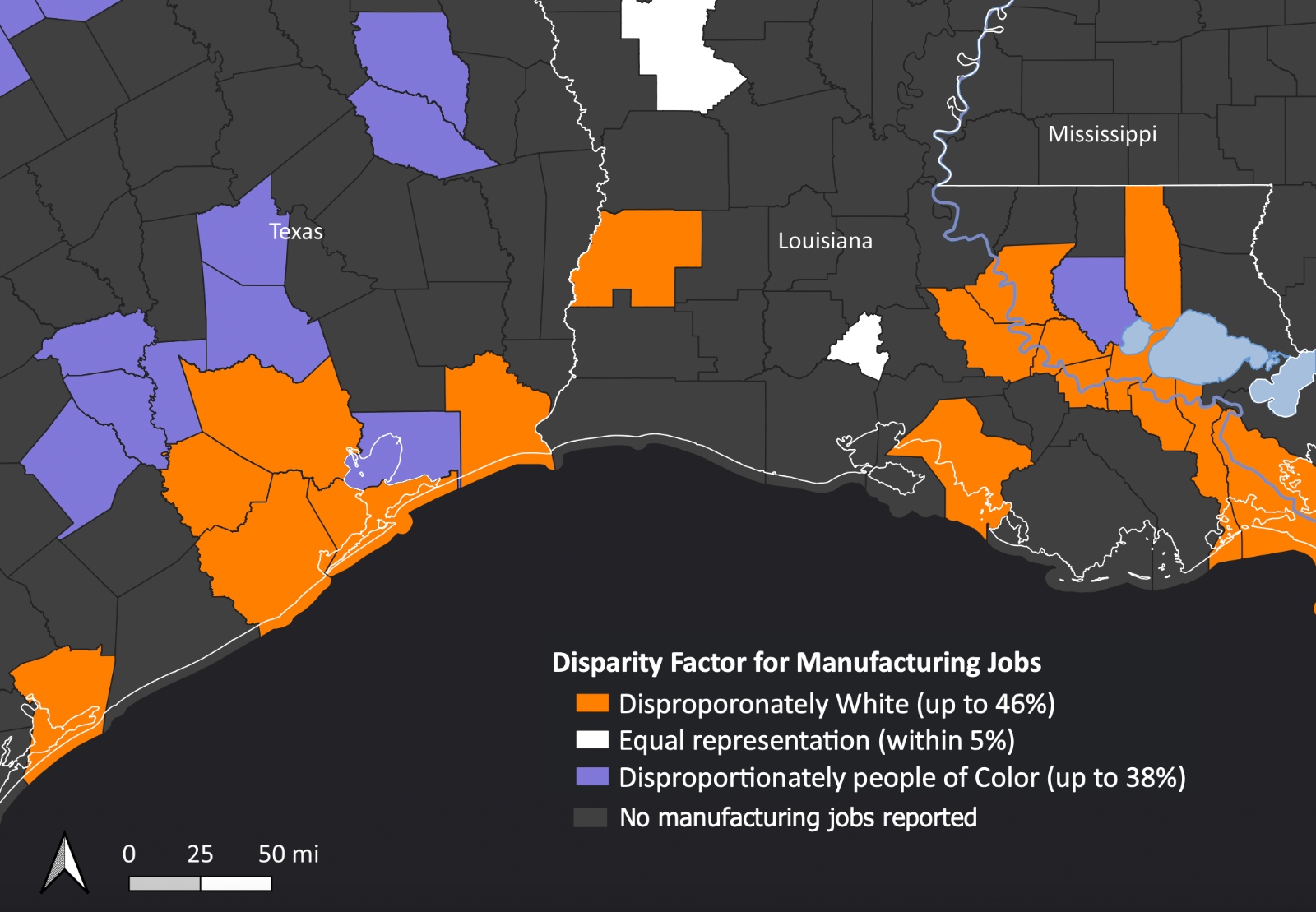

Except, according to new research shared exclusively with Floodlight, in Louisiana’s majority Black communities in the area known as “Cancer Alley” because of its high concentration of polluting industries, the majority of jobs go to white workers. Similar disparities occur in minority-dominant communities along Texas’s Gulf Coast, where the majority of workers are white.

“If one group gets all the pollution and another group gets all the jobs, it’s not really a trade-off anymore,” said Kimberly Terrell, director of community engagement and a staff scientist with the Tulane University Environmental Law Clinic who led the research team.

The highest disparity was found in St. John the Baptist Parish, home to the third-largest oil refinery in the nation, and plants that make neoprene and absorbent material for diapers.

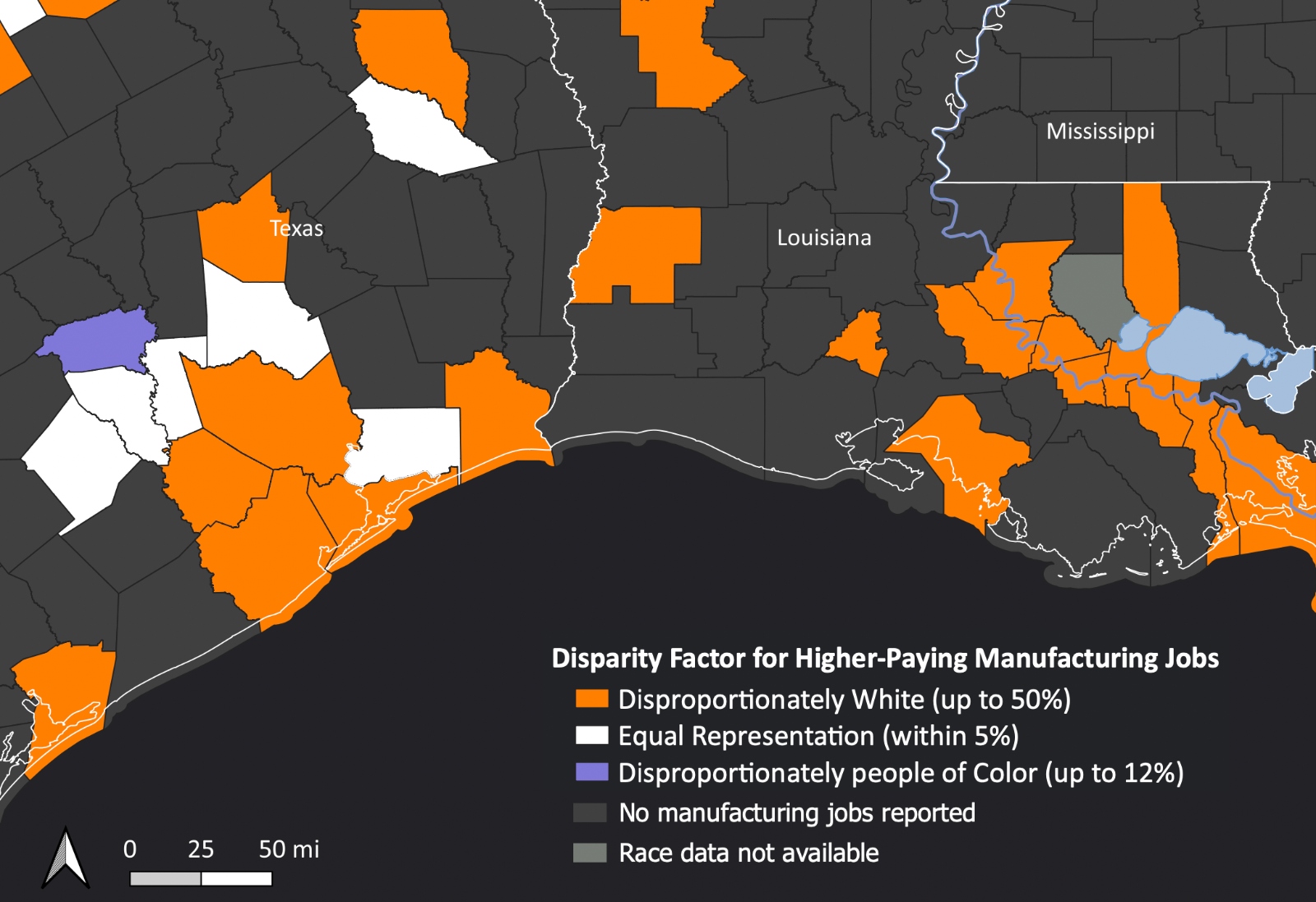

There, people of color represent nearly 70 percent of the working-age population but make up only 28 percent of the manufacturing workforce, according to initial data from Tulane. That disparity is even greater with respect to higher-paying jobs, such as managers, sales workers, and technicians. Minorities hold only 19 percent of those positions.

“I would hear the people here say, ‘These plants keep coming but they’re not hiring Black people,’” said retired educator Stephanie Aubert, who is Black and lives in St. John the Baptist Parish. “They’ll hire people from outside the parish before they hire us. That’s what they do to us.”

The second-highest disparity was found in Jefferson County, Texas, where minorities represent 59 percent of the working-age population but make up only 28 percent of the manufacturing workforce, according to the data.

Industry representatives who responded to Floodlight say they are working to increase diversity. Louisiana’s economic development agency, which gives industry generous incentives to locate in the state, says their hiring requirements don’t include any racial or location requirements.

Anne Rolfes, director of the nonprofit environmental advocacy group Louisiana Bucket Brigade, says community advocates have “known for a long time” that communities most deeply impacted by industry through toxic air emissions and other health risks are rarely offered the jobs industry and state leaders always promise whenever announcing new projects.

“The jobs claim is central to their existence,” Rolfes said. “Now we have proof, that communities aren’t benefiting from the industry, and are being disproportionately harmed by pollution.

In Texas, there are similar stories. In 2019, Darrell Kyle, a former union president for United Steelworkers Local 13-243 in Beaumont, was told by companies there they didn’t hire minorities because they typically couldn’t pass aptitude or drug tests. Kyle, who worked for ExxonMobil for 30 years, thought he could help. He recruited more than 20 people of color with criminal backgrounds or from low-income households and worked with a local nonprofit to provide vocational training designed to steer them through the hiring process at the ExxonMobil plant in Jefferson County.

“They didn’t hire any of those people, and none of the people they hired for that mechanical class were from Jefferson County,” Kyle said. “It’s a continued theme with these companies.”

ExxonMobil did not respond to a request for comment about the program.

The report from Tulane researchers, which uses publicly available data on jobs, tax exemptions, and toxic air emissions, is part of a larger analysis examining racial disparities in hiring and disproportionate pollution exposure from industrial facilities across the country. The researchers focused on Louisiana first.

“I was shocked by how consistent the findings were” with regards to the disparity, Terrell said.

Terrell used 2021 data from the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and cross-referenced it with population data reported by the U.S. Census Bureau to come up with the disparity percentages.

Other Louisiana parishes with disparities include:

- East Baton Rouge, where people of color make up 55 percent of the working-age residents but only hold 28 percent of the manufacturing jobs;

- Iberville, where 51 percent of the working-age population are minorities but only 28 percent are in the manufacturing workforce; and

- West Baton Rouge, with people of color comprising 42 percent of the working-age population but hold only 24 percent of the jobs.

Harris, Nueces, and Brazoria counties in Texas had similar disparities, with people of color making up 71 percent, 72 percent, and 55 percent of the working-age population and just 50 percent, 53 percent, and 37 percent of the manufacturing workforce, respectively.

“They’ll hold a job fair, they’ll come to your school. That doesn’t mean they’ll hire you,” said Jo Banner, who grew up in St. John the Baptist Parish and now runs a nonprofit with her sister, Joy, focused on environmental justice. Years ago, Banner was hired to run an industry job fair in the parish. It attracted more than 500 people, but Banner later learned the company only had two positions to fill. She called the event “performative.”

“What I’ve always heard, even having family members who worked in the plants, is that they are notorious for not hiring Black people — or not hiring people from the area,” she said.

Research for the study by Michael Ash, a professor of economics and public policy at the University of Massachusetts, shows residents in St. John have among the highest individual air pollution exposure risks from the petroleum and chemical industries. Counties along the Texas Gulf Coast have similarly high levels.

The industries there also get huge tax breaks, according to Gianna St. Julien, a researcher with the Tulane Environmental Law Clinic. Some industries have received tax exemptions close to $1 billion over the past 12 years.

“St. John the Baptist only received 23 new jobs within that 12-year time span,” St. Julien said. “We’re talking an estimated [$34.7 million] in tax breaks … and we’re only talking 23 jobs.”

There are no stipulations related to the racial demographic makeup of employers’ workforces, according to Mark Lorando, a spokesman for Louisiana Economic Development, the state agency that manages various incentives to attract employers to the state.

Neither the Louisiana Oil and Gas Association nor the governor’s office responded to requests for comment on findings from the report.

Marathon Petroleum Corp., which employs more than 900 people at its Garyville refinery, one of the largest in the nation, said in an emailed statement that it has provided more than $500,000 for scholarships designated for minorities looking to study industrial-related fields and for workforce development grants for local schools.

“People think these refineries are helping the community because they sponsor this or that, but all that money is pennies compared to the millions they’re making as opposed to hiring someone who would be living here, buying houses and spending tax money back here,” Kyle said.

Amal Ahmed contributed to reporting.