This story is part of the Grist series Parched, an in-depth look at how climate change-fueled drought is reshaping communities, economies, and ecosystems.

Earlier this month, as water levels in the Lake Powell reservoir fell to record lows amid the ongoing Western drought, the federal government asked seven states that rely on the Colorado River to work out an emergency conservation deal. The states had been scheduled to receive river water that was stored in the lake, but releasing the water would have drained the reservoir further, threatening its ability to generate hydroelectric power for millions of people and raising utility bills for towns and tribes across the West. The feds also revealed that declining reservoir levels would endanger the tubes that carry water past the dam’s hydropower turbine, potentially depriving multiple communities of drinking water and compromising “public health and safety.”

Late last week, the states agreed to forfeit their water from Lake Powell in order to ensure that the reservoir can still produce power. The deal puts a finger in the metaphorical dike, postponing an inevitable reckoning with the years-long drought that has parched the Colorado River — and a wrenching tradeoff between power access and water access for millions. It does so, in part, through an unusual act of hydrological accounting.

The deal has two parts. The first and more straightforward part is that the federal government will move 500,000 acre-feet of water (about 162 billion gallons) from the Flaming Gorge Reservoir into Lake Powell, bumping up water levels in the latter body. Flaming Gorge, which stretches across Wyoming and Utah, is mostly used for water recreation, so the immediate effects of the transfer will be minimal. The feds could do more of these water transfers later in the year if things get worse, drawing on water from other nearby reservoirs.

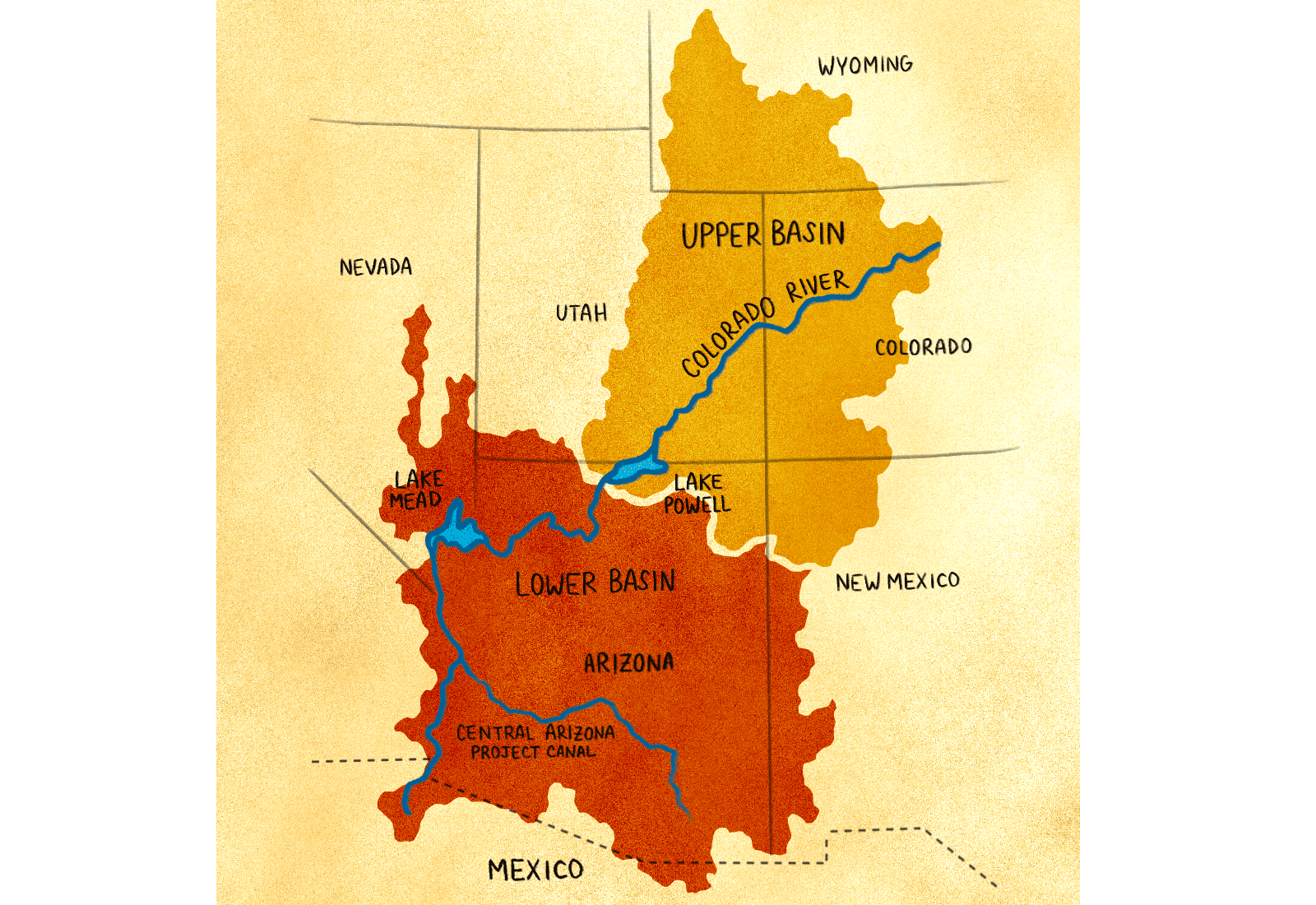

The second part is more complicated — and less helpful. In ordinary circumstances, the Bureau of Reclamation releases water from Lake Powell into an even larger reservoir called Lake Mead, from which it then flows to households and farms across the Southwest. As part of the deal, the states that rely on Mead water are agreeing to leave about 480,000 acre-feet of that water in Lake Powell, thus lowering the water levels in Mead. (Reclamation already announced earlier this year that it would delay the release of 350,000 acre-feet of water in Powell in anticipation of spring snow runoff.)

The problem is that Lake Mead’s falling water level has huge implications for water access in the Southwest. Pursuant to a drought contingency plan worked out back in 2019, declines in Mead trigger mandatory water reductions for states like Nevada and Arizona. The first of these reductions arrived last year, when the river entered a so-called “Tier 1” shortage, resulting in a 30 percent cut to Arizona’s water allocation. This has forced farmers in the Phoenix area to fallow their cotton and alfalfa fields. Officials expect the river to enter a Tier 2a or 2b shortage in the coming years, which would mean even larger cuts. Keeping water in Lake Powell makes it more likely the reservoir will reach that threshold.

The deal contains an eyebrow-raising workaround for this. In exchange for leaving the water in Lake Powell rather than having it flow to Lake Mead, the states get something in return: Officials at the Bureau of Reclamation will act as if that the water did go to Mead, thus treating Mead’s water level as though it’s higher than it really is. The hope here is to avoid triggering the cuts that would accompany a Tier 2b shortage declaration, even though the actual water level in the reservoir will likely fall low enough to warrant such cuts.

In other words, the states have agreed to ensure Lake Powell has more water than it should, and in return they get to pretend as though Lake Mead has more water than it does. The deal protects the towns and tribal communities that rely on Powell for water, but only for a short time: The ongoing drought has shown no signs of letting up, and it’s only a matter of time before water levels in Powell fall back into the danger zone, jeopardizing hydropower access and drinking water quality.

After publication of this article, the Bureau of Reclamation told Grist that it had been informed of the states’ agreement and expects to reach a formal decision on the matter in the coming weeks.

For the millions of people who rely on Lake Mead, meanwhile, the deal just postpones a shortage declaration that was bound to arrive in a few years anyway. It may give states like Arizona more time to figure out how to cope with declining water allotments, but it won’t stop cotton fields from going fallow or absolve suburbs like Scottsdale of the need to drastically reduce their water usage.

For as long as there’s a drought on the Colorado, federal officials will have to choose between hydroelectric power in communities that depend on Lake Powell and water access in those that rely on Lake Mead. The sudden advent of this new short-term deal shows not only that these decisions are not going away, but that they will arrive faster than any of the parties on the river ever thought they would.

Update: This story has been updated to include comments from the Bureau of Reclamation that were received after publication.