This story was originally published by Canary Media and is republished with permission.

The Biden administration on Tuesday received a top bid of $5.6 million during the first-ever auction of offshore wind development rights in the Gulf of Mexico.

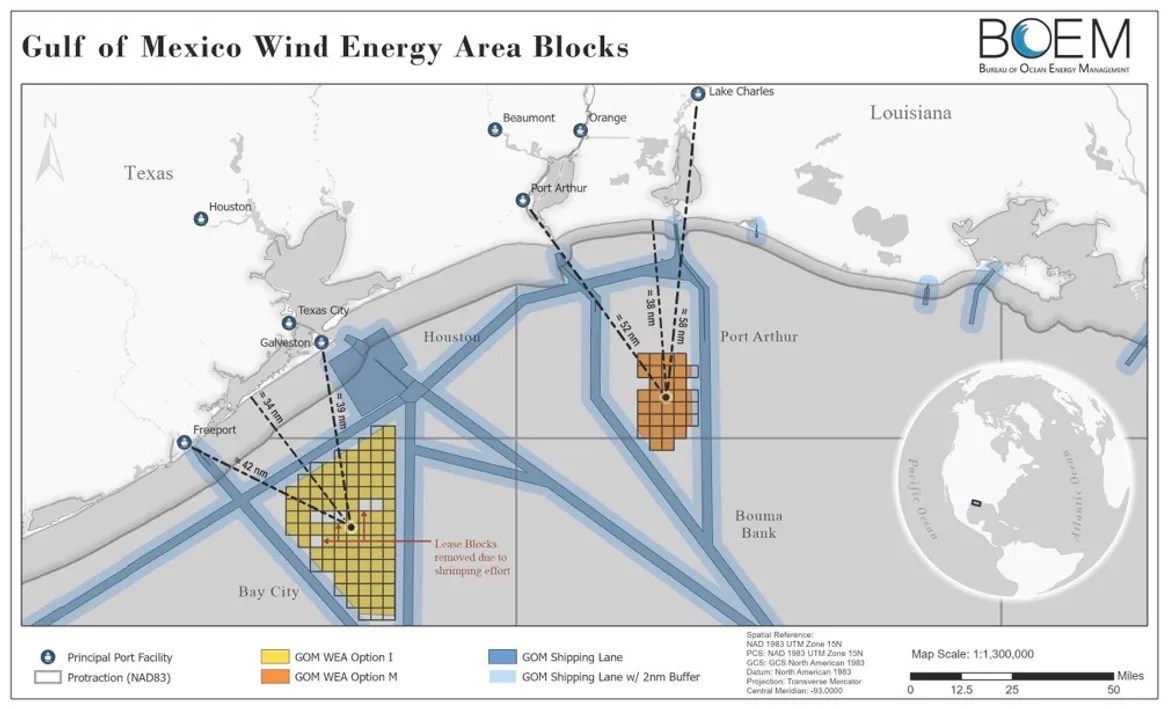

German energy giant RWE placed the highest bid for a 102,500-acre swath of water off the coast of Lake Charles, Louisiana, which has the potential to host 1.24 gigawatts’ worth of offshore wind capacity. Two other lease areas near Galveston, Texas didn’t receive any bids.

The lease sale is an important step toward building clean energy projects in a region that has long been dominated by offshore oil and gas production. Wind turbines are already spinning off the East Coast and more are being installed; meanwhile, floating offshore wind farms are being planned for California’s coastal waters. This week’s auction officially brings the emerging U.S. offshore wind industry to Gulf waters.

At the same time, the sale — which drew a lackluster response from the industry — reflects the significant challenges facing the offshore wind market in general, and the Gulf of Mexico in particular.

The U.S. Interior Department’s Bureau of Ocean Energy Management put three areas up for auction that together span nearly 302,000 acres off the coasts of Texas and Louisiana. The combined lease area has the potential to generate roughly 3.7 gigawatts of clean electricity once developed, or enough to power nearly 1.3 million American homes — though the power generated by these projects could also eventually go toward producing green hydrogen.

“While today’s auction fell short of expectations, it is nonetheless a critical step for the energy transition on the Gulf Coast,” Josh Kaplowitz, vice president for offshore wind for the American Clean Power Association, an industry group, said on Tuesday in a statement.

According to the U.S. Department of Energy, the United States now has nearly 53 GW of offshore wind projects in the early planning, permitting or construction phases — over a thousand times greater than the current installed capacity of 42 megawatts (0.042 GW). The U.S. project pipeline is booming in large part due to state policies and federal targets for developing offshore wind, including the Biden administration’s goal of deploying 30 GW of the renewable energy source by 2030.

Yet it’s far from guaranteed that all projects in the expanding pipeline will get built.

Developers along the East Coast and worldwide are grappling with recent supply-chain bottlenecks, rising material costs and higher interest rates that have made it more expensive and less profitable to install giant offshore turbines in any location. Companies behind about 9.7 GW of proposed U.S. offshore wind farms are expected to renegotiate or outright cancel their existing power purchase agreements with utilities, according to BloombergNEF.

On top of those industry-wide constraints, offshore wind developers in the Gulf of Mexico must also confront lower-than-average wind speeds — which limit how much electricity the turbines can produce — and seasonal hurricane activity that threatens to topple infrastructure. And while Louisiana has set a nonbinding goal of generating 5 GW of offshore wind power by 2035, the region’s utilities and state agencies have done relatively little to put policies in place for offtaking all the clean electricity.

“The business case in the Gulf of Mexico for offshore wind is very vague, and very uncertain,” Chelsea Jean-Michel, a wind analyst at BNEF, recently told Heatmap.

John Begala of the Business Network for Offshore Wind told Canary Media ahead of Tuesday’s auction that participants would have a “strategic vision” that looks beyond the current challenges to see the long-term market value of Gulf Coast projects.

That could eventually include supplying electricity to help produce hydrogen at facilities across Louisiana and Texas. Last week, the hydrogen production company Monarch Energy said it was exploring building a $426 million plant in Louisana’s Ascension Parish. The facility would use electrolyzers to split water into hydrogen and oxygen — a process that requires using massive amounts of clean energy to be considered “green.”

Large energy companies like RWE are also well-positioned to create new turbine technologies that can perform well in the region, said Begala, who is the network’s vice president for federal and state policy. Shell, for example, has invested $10 million in Gulf Wind Technology to build an “accelerator” hub in Louisiana that will develop offshore wind products optimized for the Gulf.

Slow winds and hurricanes “are environmental conditions that are found throughout the world,” he said. “If Gulf of Mexico [developers] can figure out these twin challenges, you’re going to see that technology explode worldwide, and it’s going to have a major impact on global production,” he predicted.

Putting towering turbines in the Gulf would also boost the region’s own emerging offshore wind economy. At shipyards in Louisiana and Texas, hundreds of workers are already busy building specialized vessels for installing turbines and substations that help bring offshore wind energy to the onshore grid.

Environmental-justice groups said they welcomed this week’s offshore wind auction, citing the urgent need to replace heavily polluting fossil fuel projects with new industries that can ideally benefit the communities that have long suffered from poor air quality, a degraded environment and, increasingly, rising sea levels and other consequences of a warming planet.

But environmentalists also expressed disappointment that BOEM didn’t include incentives for developers to create “community benefit agreements” in the lease terms, as the agency did in California’s offshore wind auction last year. These legal agreements stipulate the terms a developer agrees to provide — including workforce development opportunities and other economic contributions — in exchange for earning the local community’s support. The lease terms do offer a 10 percent credit to developers who contribute to a fisheries compensation fund for commercial fishing outfits, but nothing similar for communities.

“The Gulf South is uniquely vulnerable to both [oil and gas] pollution and to climate impacts, and so we expected to see the same — if not more — benefits headed to the region,” said Kendall Dix, the national policy director for the nonprofit organization Taproot Earth.

Still, he added, local communities will potentially have another opportunity to advocate for and negotiate such terms when developers and utilities forge power purchase agreements in the coming years, or when BOEM opens additional swaths of the Gulf of Mexico to offshore wind development.

“The [Biden] administration has been saying that they want to make justice a priority,” he said. “I just think that the moment calls for something bigger.”