In less than four months last fall, the Southern California city of Carson experienced a sizable earthquake, major gas-flaring events at local refineries, a multi-day warehouse fire, an odor-induced state of emergency declaration, and a 9-million-gallon sewage spill. Over that period, one toxin – hydrogen sulfide – reached levels that were 230 times higher than the state’s safety standard, leading to the overwhelming stench and state of emergency declaration. Hydrogen sulfide, or H2S, is a gas regularly emitted during oil production, and it can be lethal at high levels of exposure. More commonly, it causes dizziness, headaches, weakness, unconsciousness, and upset stomachs.

During that time, Ana Meni joined more than 3,400 families who local authorities relocated from their homes due to the debilitating odor, which made it “impossible” to be both outside and inside, as the smell became “trapped” in residents’ homes. For 40 days, she lived in a single hotel room separated from the rest of her family, all while symptoms that developed after the toxic events caused her sister to experience incessant nose bleeds, bouncing in and out of the hospital.

“It’s like walking on eggshells every day,” Meni said of life in the 90,000-person city. “You’re afraid to look over your shoulder for what’s next.”

Carson, which is adjacent to the massive Port of Los Angeles, is home to 175 industrial sites, including a network of five refineries and a growing number of logistics warehouses, according to a database maintained by the South Coast Air Quality Management District, or SCAQMD, Southern California’s air pollution regulator.

Many local advocates believed that the fall’s cascade of crises could be traced to regulatory violations by multiple industrial actors in the city — but SCAQMD says otherwise. Since Carson’s debacles began, the district has taken action regarding only one of the pollution events: the warehouse fire. In December, the regulator issued violations against the warehouse owners — Liberty Properties and its parent company, Prologis — designating them as the main culprits behind Carson’s elevated H2S readings and related state of emergency declaration.

Now, residents are going to court to interrogate the role of other industries in Carson’s crises. A new class-action lawsuit questions the results of SCAQMD’s investigation, calling for increased accountability from Carson’s industrial community. In conjunction with the warehouse owners, the suit names the Marathon Refinery in Carson, which is California’s largest refinery and has a history of violating pollution standards. It alleges that while the September 30 warehouse fire led to elevated H2S levels in Carson, Marathon also “negligently” released hazardous chemicals into Carson’s air and water before and after the fire. When coupled together, the lawsuit argues, Carson’s state of emergency was born.

The lawsuit, brought by Cotchett, Pitre & McCarthy, a law firm that specializes in environmental litigation, asks for the creation of a community fund to be dispersed to help offset medical costs, lost wages due to residents’ displacement, and relocation funds for residents attempting to permanently flee the pollution-plagued city. It also asks for tighter regulations for the warehousing industry and Marathon Refinery, calling on Liberty Properties, Prologis, and Marathon to “repair and restore” areas impacted by the “release of toxic gas.” In the end, community members are fighting to “ensure no future risk of [toxic gas] discharge, fire or other catastrophic events” due to industrial activity in Carson.

The lawsuit seems to reflect the fact that the narrowness of SCAQMD’s findings were taken as something of an anti-climax, given the finger-pointing that followed the events of the fall. Amateur internet sleuths and local politicians alike speculated about various industry actors who might be behind Carson’s debacle; many even pointed to a Southern California oil spill that dominated headlines in early October. At one point, Carson Mayor Lula Davis-Holmes publicly said that the gas was from a “leaking pipeline” believed to be connected to a local refinery owned by the Marathon Petroleum Corporation. The pollution board disputed that.

SCAQMD told Grist that over the last several months it has “examined all local petroleum refineries, including on-site inspections at the Marathon Refinery in Carson.” The district said its investigation failed to reveal “any evidence that a refinery, oil pipeline, or other direct petroleum emission source played a role in [Carson’s state of emergency declaration].”

Data shared with Grist by SCAQMD shows that, from October 7 to November 2, the air district took approximately 100 readings for H2S outside of the Marathon Refinery. Roughly 80 percent of those readings were above state limits, with readings peaking at 4,000 parts per billion – 133 times higher than state standards – on October 16.

“South Coast AQMD inspectors determined that the source of the H2S emissions detected was the Dominguez Channel itself, and not the refinery,” an SCAQMD spokesperson told Grist. The spokesperson also said that the emissions readings could not be compared to state limits, because the readings are point-in-time measurements rather than hourly averages, like the state limits. SCAQMD did not elaborate on how the district determined the precise origins of the emissions emanating from the channel. Representatives from Marathon did not respond to Grist’s request for comment.

Every day, Meni sees smokestacks from the Marathon Refinery – the largest refinery west of Texas – from her backyard. In 2020, it dumped 1.2 million pounds of toxins into the air. Three more refineries lie within five miles of her home.

“You won’t understand how unshakable it is unless you live it,” Meni said of the pollution in her neighborhood. “You wouldn’t understand me explaining how when the pollution gets so bad and the smells are so strong when you’re driving through your city, you have no option but to slam on the brakes, bust open the door, and start throwing up on the road.”

Residents in her census tract, 44 percent of whom are immigrants and almost all of whom are people of color, experience more air pollution than 97 percent of the country, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Social Vulnerability Index, the census tract’s vulnerability to natural or human-caused disasters is 95.5 out of 100, 25 percent higher than the average of Los Angeles County at large.

Carson’s recent ordeal began in mid-September, according to the lawsuit. “Unbeknownst to the residents living in its shadow,” the lawsuit reads, “in the early morning hours of September 16, 2021, [Marathon] saw an unprecedented spike in its fence line monitor Hydrogen Sulfide readings, at nearly 290 parts per billion” — almost 10 times higher than the H2S standards California adopted in 1969.

The very next day, the city was the epicenter of a 4.3-magnitude earthquake. The natural disaster set off a domino effect: Within minutes, the earthquake caused the refinery to begin flaring, a process in which combustible gases are burned off in a controlled way so that they don’t collect inside a plant at dangerous levels.

Over the next two days, the refinery reported releasing more than 1,000 pounds of nitrogen dioxide, 500 pounds of sulfur dioxide, and 200 pounds of H2S. (In many oil and gas operations, H2S and sulfur dioxide emissions are inseparable, because H2S is flared to produce sulfur dioxide.) As first reported by Grist, the refinery disclosed to the governor’s office that some of these toxins may have been directly released into the Dominguez Channel, a 15-mile watershed that cuts through Carson and feeds into the Pacific Ocean.

The Marathon Refinery is one of at least 100 industrial sites permitted to dump directly into the channel, according to the county’s Department of Public Works. Across Los Angeles County, multiple refineries discharge millions of gallons of oil and gas byproduct into the channel daily — including Marathon, which is permitted to discharge 8.32 million gallons into the channel every day.

Two weeks later, on September 30, a massive fire ripped through a cosmetics warehouse on the border of Carson and neighboring Gardena, six miles away from the refinery. In the days following the fire, hundreds of pounds of charred debris, including ethanol-based hand sanitizer, made its way into nearby storm drains connected to the Dominguez Channel. This led to the decay of organic materials in the channel, resulting in substantial emissions of H2S, according to SCAQMD, which cited this as the event that ultimately led to the state of emergency.

Then came the smell. For more than six weeks, the air reeked of something new. The musky, thick gray air in Carson, normally filled with the aroma of petroleum, was replaced with the funk of months-old rotten eggs and sewage. Some called it “the stench of death.”

According to the lawsuit, residents “started feeling sick, suffering from nausea, vomiting, irritation of the eyes, skin and throat and headaches: all symptoms of noxious gas exposure.”

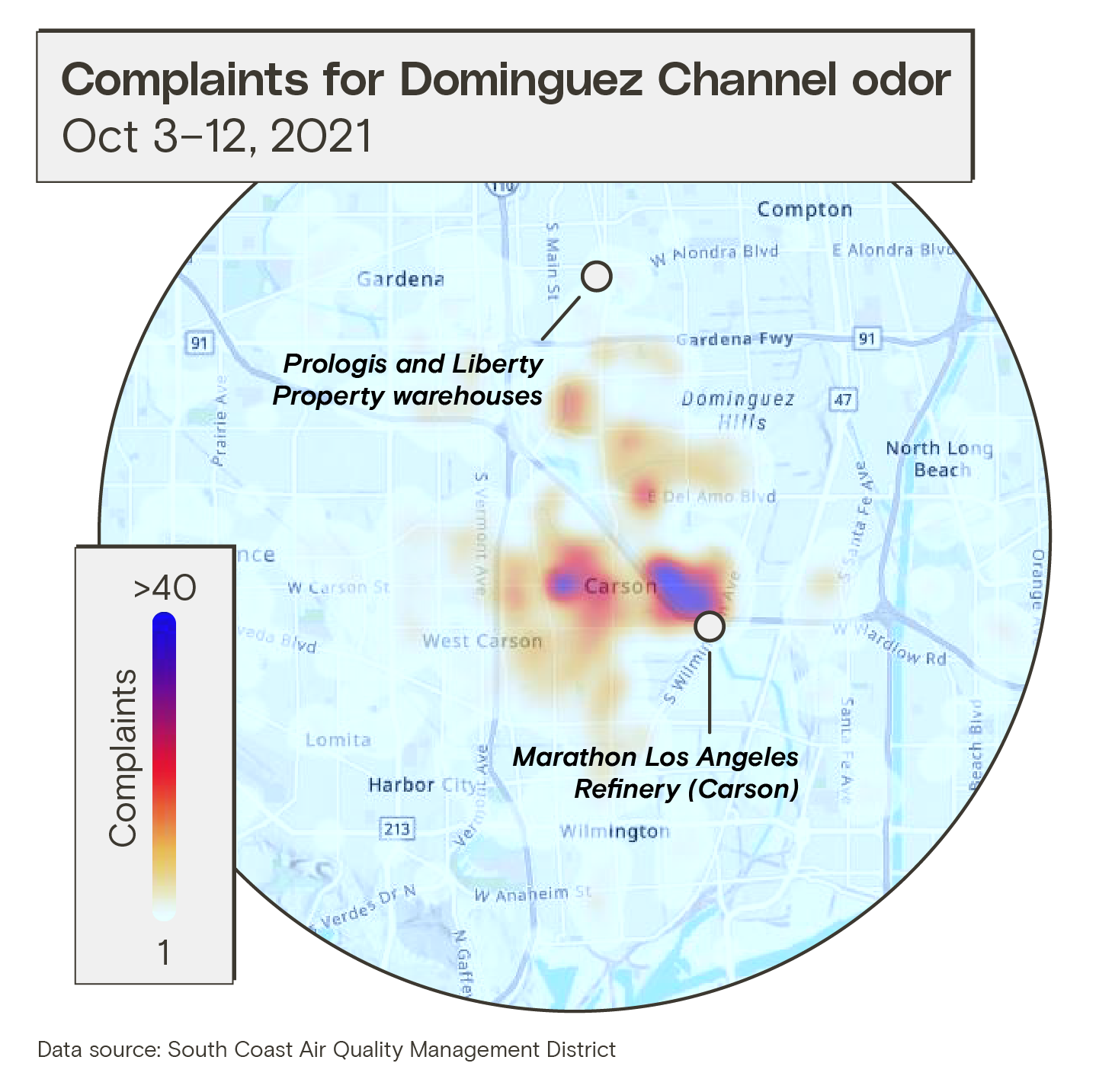

Meni says the smell was strongest at the bank of the Dominguez Channel by the Marathon Refinery. The air district’s complaint map supports this assertion: The resident complaints it received appear to be concentrated in this area. In the first week, SCAQMD received 5,000 complaints from residents of Carson and surrounding communities.

“We all had no idea what was in the air giving us uncontrollable migraines and nosebleeds,” Meni said.

The smell was so bad that more than 3,400 families had to be relocated from their homes to area hotels across sprawling Los Angeles County. In all, more than 20,000 families required support from city and county officials, nearly 40,000 home air filters were dispensed, and an estimated $55 million was dished out by local governments to treat the contaminated water in the channel and offer mitigation services to residents.

While all of this was happening in October, the refinery continued releasing H2S at elevated concentrations, according to SCAQMD’s data. The lawsuit claims that nightly readings continued to surpass state limits until November. At one point in October, hydrogen sulfide levels in Carson’s section of the Dominguez Channel reached nearly 7,000 parts per billion, about 230 times higher than the state’s standard, according to an air district report.

To make matters worse, while the rotten egg smell still lingered in the area’s air, on the last night of 2021 a sewer line busted under a Carson freeway exit, dumping more than 8 million gallons of sewage into the channel. While the spill did not contribute to the city’s H2S saga, it added a new odor to Carson’s air as the channel and dozens of miles of Southern California’s coastline were flooded with excrement. The event is expected to be investigated by the county’s departments of Public Works and Public Health.

“It’s a nonstop dogpile,” Meni said of the cascade of events.

Over the coming months, Meni and a handful of other residents will be represented by Cotchett, Pitre & McCarthy, which has won more than $1 billion in environmental suits since 2010. While she is hoping to recoup some of the financial resources drained from her family when they were forced out of their home, Meni also wants to make sure Carson doesn’t suffer from a similar set of toxic events again.

“When I look at other areas, more affluent areas, stuff like this doesn’t happen,” she said. “Residents don’t have to claw for representation — they’re not forced out of their homes, and they’re not left behind.”

Update: This article has been updated to incorporate additional comments received from SCAQMD after publication.