In the Piedmont region of North Carolina, about 50 miles east of the Blue Ridge mountains, a thin, 25 mile-long belt of ore stretches north from the southern state line. The strip, called the Carolina Tin-Spodumene Belt, contains the country’s largest hard rock deposit of lithium.

Back in the 1950s, lithium gained importance as a component of nuclear bombs and pharmaceuticals, and the area around Kings Mountain, near Charlotte, saw a major boom in mining. For about 30 years, the region supplied almost all the lithium in the world. Then in the 1980s, production moved to lower-cost operations overseas. Today, less than 1 percent of global lithium is mined in the United States, all from one mine in Nevada; the vast majority comes from Chile, Australia, and China.

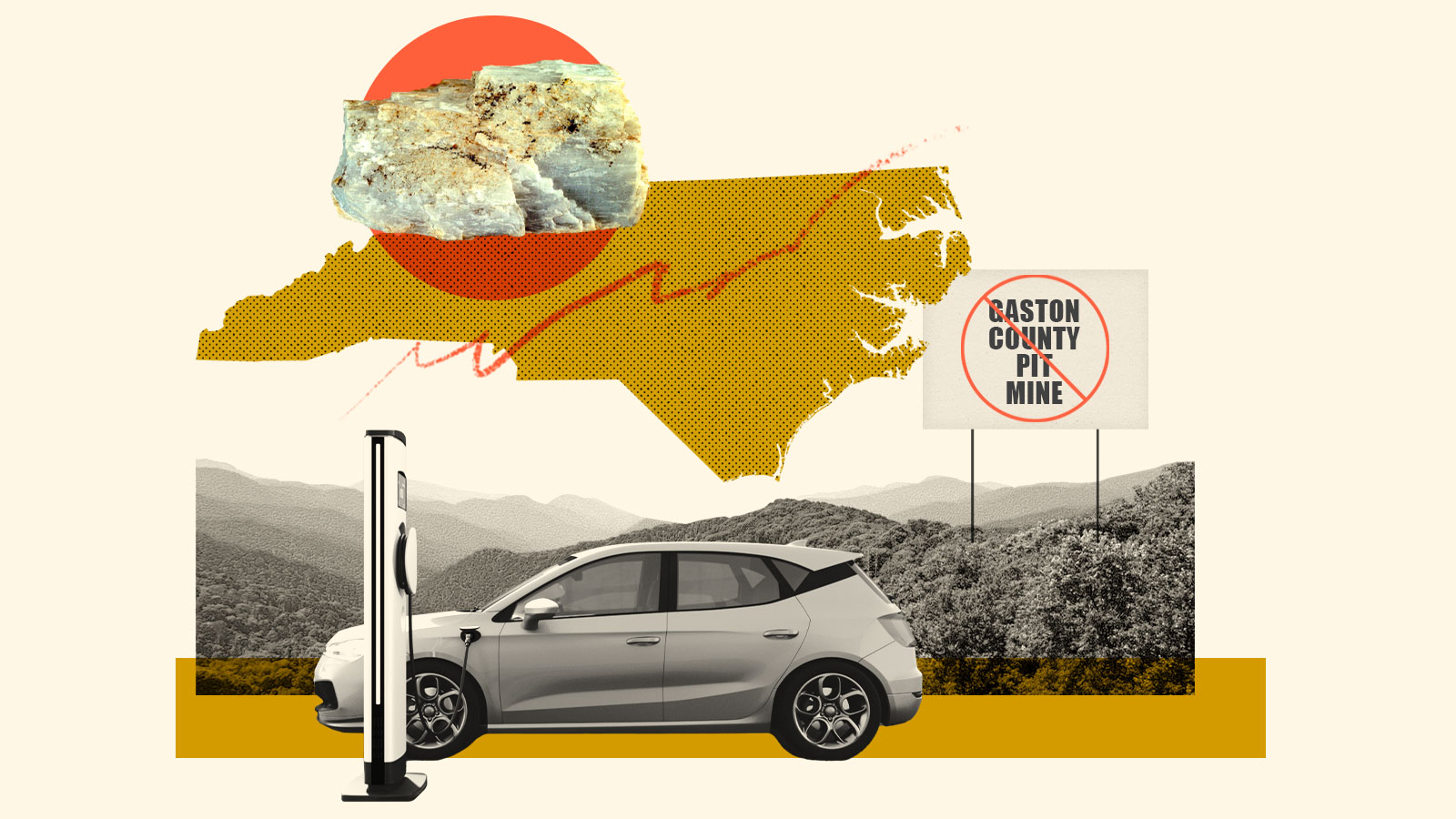

But as nations seek to cut emissions and transition to clean energy sources, demand for the metal is increasing, and the U.S. is looking to ramp up production within its borders. Last summer, President Joe Biden signed an executive order calling for electric vehicles, which depend on lithium-based batteries, to make up 50 percent of all new vehicle sales by 2030. The Inflation Reduction Act, recently signed into law, aims to incentivize a domestic battery supply chain, providing tax breaks for mines and credits for electric cars and grid storage applications when a percentage of the battery is produced or recycled in the U.S.

Now, mining companies are once again eyeing North Carolina as they seek to capitalize on the booming market for electric vehicles and renewable energy storage. The U.S. Geological Survey estimates that three known spodumene deposits in the region – around Kings Mountain, Bessemer City, and Cherryville – contain a combined 426,600 metric tons of lithium. That amount, which includes reserves that could be economically extracted at present as well as other estimated resources, would be enough to supply batteries for over 50 million electric vehicles.

Piedmont Lithium Inc., a 2016 Australian startup, acquired thousands of acres in Gaston County and signed a deal to supply lithium to Tesla in 2020. It ultimately relocated its headquarters to North Carolina last year. Albemarle, a specialty chemical manufacturing company and one of the largest lithium producers in the world, has invested about $100 million in a possible project in neighboring Cleveland County.

Courtesy of Albemarle

“Over the last 18 months we’ve seen a 700-percent increase in lithium pricing, which is a genuinely insane price increase,” said Daisy Jennings-Gray, a senior price analyst from Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, which researches battery and electric vehicle supply chains.

But lithium mines around the world and across the country face controversy for their environmental and social impacts. And just as interest in this North Carolina region, with its deep reserves, long mining history, and growing presence of battery and electric car plants has risen, so too has local opposition. The Piedmont region is emerging at the latest battleground in the debate over whether clean technology is truly clean for everyone, with residents and policymakers in different communities divided.

Piedmont Lithium’s land sits in the northwest corner of Gaston County, near Cherryville, on the outskirts of Charlotte. Surrounded by large swaths of forest and working farmlands, the community is popular among transplants from New York and California, “but it’s also multi-generational farms, homegrown people who have lived here all their lives,” said Chad Brown, a member of the Gaston County Board of Commissioners.

The company started buying land in Gaston County in 2016, ultimately acquiring or gaining mineral rights to over 3,000 acres. In 2018, it told investors that it expected to obtain the necessary permits the following year to build an $988 million extractive hub and processing facility. The vision included four 500-foot deep mines and a chemical plant that could convert the mineral spodumene into 22,700 metric tons of lithium hydroxide annually.

By September 2020, Piedmont Lithium had signed a deal to supply Tesla a third of the mine’s annual output, enough to power at least 350,000 Teslas a year, for up to 10 years. It hadn’t even applied for state permits and a county zoning variance yet. It took another year before the community heard the detailed proposal for the mine, at Piedmont Lithium’s first public meeting before the Gaston County Commissioners last summer.

“It was the worst rollout of an economic development plan ever,” Brown said. “They went to every stakeholder before they came to us.”

An outpouring of public pushback has effectively stalled the project. Residents say their questions about loud blasting, increased truck traffic, vibrations, dust, and air quality have not been adequately addressed by the mine. The county board of commissioners put a temporary moratorium on mining to update their local codes last year; they also hired an independent hydrologist. Digging a large open pit in the ground lowers the water table, plus the spodumene refining process is both water- and carbon-intensive. It produces chemical waste at multiple intervals with potential for spills and surface and groundwater contamination; residents worry their wells and rivers could be poisoned or run dry.

“They said the operation will be completely safe,” said Lisa Stroup, who lives two miles south of the proposed Piedmont Lithium site and worked at a lithium hydroxide plant in nearby Bessemer City. “Having worked with lithium, I can tell you there is nothing safe about it,” she noted of the highly caustic and erosive metal.

A sign signals opposition to a proposed mine in Gaston County, North Carolina. Many residents have taken a stand against Piedmont Lithium’s proposal to develop a lithium mine in the area. Right, felled logs rest on land owned by Piedmont Lithium. Photos courtesy of Stop Piedmont Lithium

Stroup lives one mile north from an old Hallman-Beam lithium mine that was eventually purchased by the company Martin Marietta and mined for gravel. “Back when they were actively mining quarry rock, this place was a dust bowl,” said Stroup. Historically and today, Gaston County contains arsenic levels above EPA standards in several public drinking wells, a phenomenon associated with hardrock mining.

“Anytime someone gets sick around here everyone says, ‘I’m pretty sure it’s something in the air or in the water from the mine,” she said.

In the ongoing permitting process, the state has expressed concerns about Piedmont Lithium’s chemical disposal plans; the company recently requested a 180-day extension to complete its Leaching Environmental Assessment Framework, a system for evaluating the release of potentially harmful substances for a variety of solid materials, including mine waste. If it does acquire state permits, it still needs to apply for zoning changes from the county board of commissioners, several members of which have already spoken out against the project.

Lithium deliveries from Piedmont to Tesla were supposed to start as early as this summer, but the company is now targeting 2026. Meanwhile, Piedmont Lithium is being sued by its shareholders for failing to disclose information about permits and local opposition that caused stock prices to fall. At this point, the company has only done exploratory drilling at the site and recently invested in mines in Ghana and Quebec to source lithium while the North Carolina project is delayed.

“I don’t feel like we’ve won yet at all,” said Stroup. She and other local residents are still waiting for the outcome of the state mining review. “We’re not against alternative fuel sources or modes of transportation, but we feel there have to be better answers.”

In adjacent Cleveland County, lithium mining is being received more favorably. Scott Niesler, the mayor of Kings Mountain, supports Albemarle’s plan to reopen and expand a shuttered lithium mine right outside of town.

“Mining has been part of the fabric of the community since the 1920s,” said Scott. “And Albemarle is a strong, established company that would be a good corporate citizen.”

One of the biggest lithium players on the market, Albemarle produces about a third of the world’s lithium, mostly from mines in Australia and South America. It also runs the country’s only fully operational lithium mine in Silver Peak, Nevada, where the metal is mined from brine rather than spodumene.

Headquartered in Charlotte, Albemarle already has a presence in Kings Mountain, where it runs a research facility and operates one of the area’s two plants that produce lithium hydroxide, a compound valued for its ability to hold a charge for long periods of time, making it the best for high-energy-density batteries. Approximately half the material for the plant comes from the company’s Nevada mine, and the rest comes from Chile.

In 2015, Albemarle bought a water-filled pit from Rockwood Lithium. The mine had been operational from the late 1930s to the 1980s and Albemarle is looking to reopen the site, expanding and deepening the pit. “There’s already a hole there,” said Niesler, pointing out that the area is already zoned for industrial use.

Albemarle has been doing environmental impact studies and acquiring more acreage through deals with landowners, but “we have not made a final investment decision thus far,” said Alexander Thompson, Vice President of Lithium Resources for the company. “Our pathway to production is subject to community engagement.”

The company had its first formal community meeting in March and has promised to host quarterly town halls. It’s also planning to open an office in town where people can stop by to ask questions.

Still, engagement can only go so far when so much remains unknown about the environmental impacts of lithium mining in the area; Albemarle readily admits the studies will take years, and a mine wouldn’t open until 2027. At the first town hall, which overflowed from the city council chamber into the hallway, questions arose about dust, traffic, water, and hazardous waste.

While lithium extraction methods have improved over time, and Albemarle has mentioned wastewater recycling and land reclamation, “there is really no benign way of getting minerals out of the earth,” said Timothy Johnson, an expert on energy, natural resources, and the environment at Duke University.

The project scope is not yet defined, but Thompson said that 70-100 households would be directly affected by operations on the land the company already owns, and they have already been contacted.

Henry Hartleb, who moved to the area from Illinois in 2012 and is now retired, lives 75 feet off the old mine site. He recently agreed to an offer of $290,000 for his one-acre property and mill house. But he worries that the offers are too low for his neighbors to buy something comparable in the area.

“I don’t see it having much economic benefit to the community,” said Hartleb. Still, he thinks the project will go through. “People here are older, 75 percent are from the area. It’s poorer than Gaston County too, and it’s a mining community. There’s already a company continually mining for gravel at a quarry right next to the mine.”

Clay Bruggeman, whose home abuts properties purchased by the mine, has yet to make a decision to sell. “We have a nice life here, but if the city and the mine want this to happen it’s probably going to,” he said. “I have to think about what’s best for me and my family.”

In addition to the mine, Albemarle has announced plans to create a “mega-flex” lithium conversion facility in the U.S. Southeast that would process up to 100,000 tons of lithium per year. According to Thompson, the Kings Mountain mine would provide half the raw material for the new plant. “This has the potential to be a multi-decade operation,” he said.

North Carolina’s vast mineral reserves are just one of the reasons the state is being eyed as the next lithium hot spot. The region, a longtime hub for car manufacturing, is now poised to become a hub for EVs. Both Toyota and VinFast, a Vietnamese car maker, have announced plans for battery plants in North Carolina. Ford and Volkswagen are setting up EV assembly plants in Tennessee and battery manufacturers, including Korean SK Innovation in Georgia, are setting up shop across the Southeast.

At the moment, while the U.S. is the second biggest lithium user in the world, domestic battery plants import almost all materials from abroad. That’s all part of why Albemarle and Piedmont Lithium want to source lithium locally in the area.

But the region also exemplifies an uncomfortable truth in the energy transition. Studies emphasize the need for a rapid transition to carbon-free transportation if the U.S. hopes to have any chance of meeting clean energy goals. But clean energy is only clean when you consider the variable of atmospheric carbon; mining still has local polluting impacts.

Often, mines get developed in places where residents have less political clout and resources to push back. In the U.S., 79 percent of lithium sits within 35 miles of Indigenous lands. Lithium America’s proposed lithium clay mine at Thacker Pass, sacred land to the Northern Paiute and Western Shoshone, faced vehement opposition from tribes, ranchers, and environmental groups before receiving its permits in February. Around California’s Salton Sea, where trials to commercially develop lithium from geothermal brines are ongoing, several tribes have raised concerns about impacts to their ancestral lands and exclusion from the decision-making process.

In other parts of the world, local pushback to lithium mining has stalled projects in Serbia and Australia. In Chile, where lithium mining from brines has sucked Indigenous lands dry, a left-wing government is attempting to regulate the industry. Environmental justice groups and others concerned about the impacts of mining have often called for more transformative transportation planning that reduces the need for cars altogether (This would also be necessary to meet emission reduction targets). They have also called for developing recycling capacity as an alternative source of metals.

“It takes seven to 10 years to build a new mine, and even companies that have done it for years face new problems when they try to ramp up lithium production,” said Jennings-Gray of Benchmark Mineral Intelligence. As the U.S. scales up lithium mining, the current lack of any cathode capacity in the country means the metal is shipped overseas, a barrier for a fully domestic EV supply chain. “[North Carolina] is an interesting one to keep an eye on and could certainly produce some significant domestic volumes,” said Jennings-Gray. “But no matter what, it’s going to be a slow climb.”