This story from InvestigateWest was produced as part of a collaboration with the Center for Public Integrity, Columbia Journalism Investigations and Type Investigations. It is republished here with permission.

From her driveway in the early evening of Nov. 14, Maryann Snudden could see the Nooksack River — its bank typically a mile away — creeping over the main road in Everson, a city of 2,500 tucked in the foothills of the Cascade mountains in northwest Washington. The swelling river swallowed roadside shrubs and drew closer to her doorstep. And closer.

The sound of pummeling rain boomed through the darkness. By midnight, three feet of water pooled in Snudden’s living room. Soon, an avalanche of debris and freezing floodwater overtook the home that Snudden, a widow, had bought with her mother-in-law only three years earlier.

“The water ripped through so quickly that it shoved my bed through the wall,” Snudden recalled.

The deluge reached as high as the ceiling, inundating furniture, photos, clothes, books, electronics, everything. In the kitchen, the powerful currents pried two refrigerators and a water heater off the floor. Outside, the water swept Snudden’s 30-foot ski boat across the nearby blueberry field.

Snudden, 52, and her mother-in-law, 74, were trapped. Snudden’s son — who lives in a different city — took to Facebook, imploring anyone with a boat to rescue them. “By the time anyone could even come and help, there was six feet of water right out the front door,” she said.

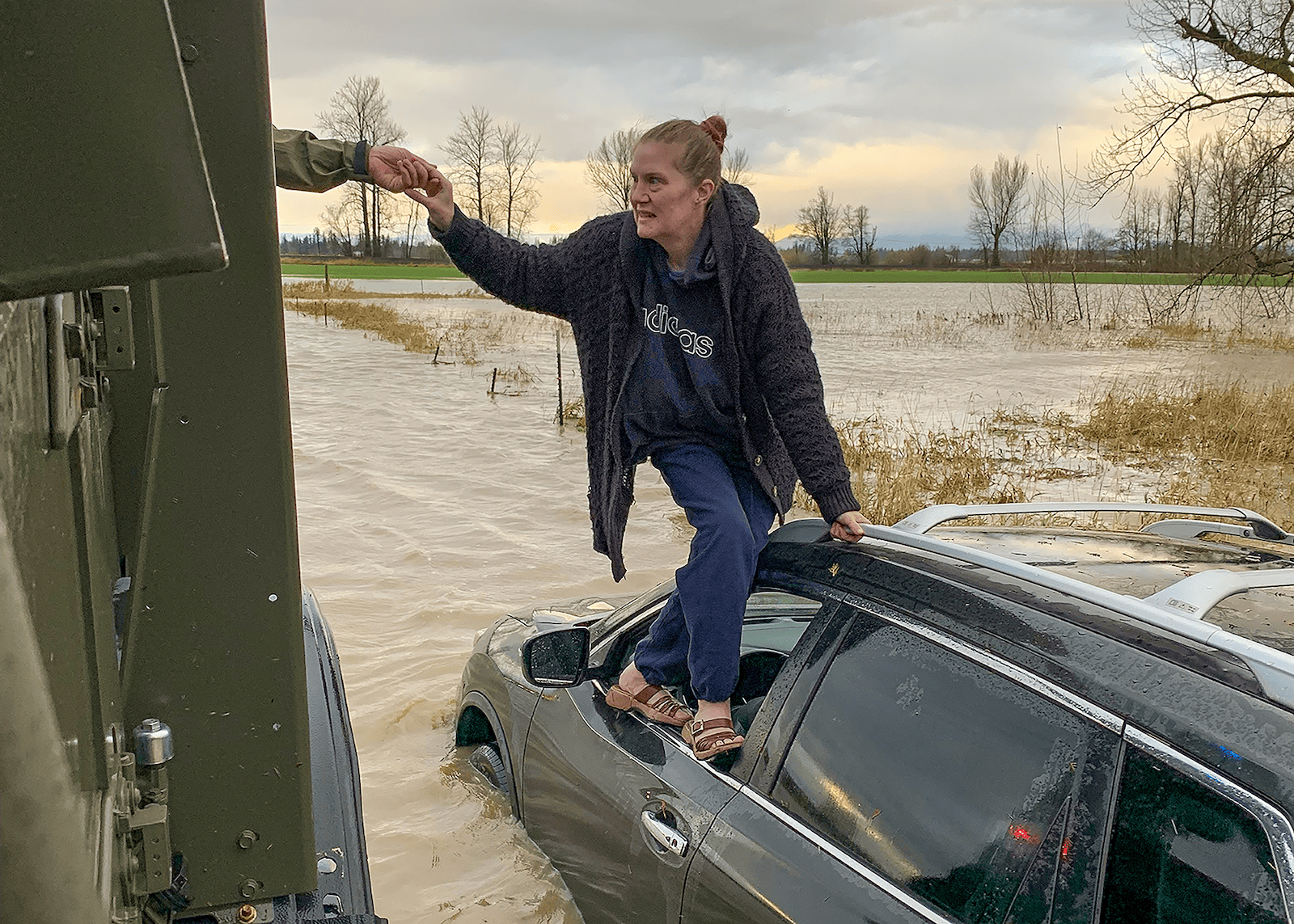

It was around 5 p.m. the next evening when they were finally rescued, pulled into a boat while the river battered their waterlogged home.

It’s been more than seven months since the Nooksack River broke free of its banks and steamrolled through the cities of Whatcom County, in the northwest corner of Washington bordering Canada. Once a lush, vibrant place sandwiched between Puget Sound and the Cascades, Whatcom County today is home to hundreds of people like Snudden, who lost everything in the November 2021 flood and continue to shuffle between hotels, damaged homes, and travel trailers, pinning their hopes on an overwhelmed Federal Emergency Management Agency.

FEMA has come under fire in recent years for failing to meet the immediate needs of survivors after major disasters. Critics say its programs are inequitable and that long wait times for its home-buyout projects make them useless for many.

“The FEMA process is cumbersome to navigate. The help that does come takes a long time to get here, and it’s not nearly enough,” said Everson Mayor John Perry, who like many others in Whatcom County had anticipated more immediate and widespread federal assistance in the wake of the devastating flood.

FEMA itself makes it clear that its capacity is inherently limited. In an email response to InvestigateWest, FEMA stressed that its “programs alone are not designed to make survivors whole again, but they can provide stability and access to additional resources needed to begin rebuilding and recovering from the floods.”

“These disasters are always locally led, state coordinated, and federally supported,” said Stacey McClain from the Washington State Emergency Management Department. According to FEMA, “the road to recovery” requires additional resources from community organizations, insurance, low-interest loans, and other local, state, or tribal agencies.

But disasters on the scale of November’s flood are far beyond the capacities of community-based relief groups, highlighting the lack of resources available at the local, state, and federal levels, Perry and other officials said.

Besides, climate change is creating further strain on FEMA’s mission to help people before, during and after a disaster, because billion-dollar disasters in the U.S. are happening every 18 days on average, according to Climate Central, an independent climate science and research organization. The damages caused by coastal and riverine flooding are projected to cost $40.6 billion each year by 2050 — a 26 percent increase — regardless of whether or not global carbon emissions reduction targets are met.

“Over the 20th century, responsibilities for emergency response got very consolidated at the federal level, particularly in FEMA,” said Anna Weber, a senior policy analyst with the Natural Resources Defence Council, a nonprofit environmental advocacy group. She recalled an analogy a colleague once made on the subject. “They said, ‘After a disaster, everyone expects FEMA to come in with giant airplanes and drop bags of money out with parachutes.’ But the reality is much more complicated than that.”

And so, officials acknowledge, people devastated by major disasters in America are often left waiting for help that may never come.

“We were left alone!” Snudden said. “We were left alone to fend for ourselves, and in places that we couldn’t even live in.”

The immediate emergency response fell to state and local officials. Mayor Perry, local police and community members equipped with boats and trucks worked tirelessly to reach those in need. Incredibly, only one person was killed, but during the crisis, the 911 dispatch had a queue of more than 100 pending rescues.

Snudden’s 911 call didn’t get any response from police, and it was Perry who rescued her and her mother-in-law in the end.

In the days that followed — after the river receded back to its designated banks — the community banded together to begin the slow, arduous process of recovery: slinging sandbags, shoveling silt from roads and driveways, fishing valuables out of soggy houses, helping wash each other’s soiled clothes, and lending a hand wherever one was needed.

Perry, the mayor, and people like Snudden all began to ask the same question: “Where is FEMA?”

A presidential major disaster declaration was finally made on Jan. 5 — 51 days after the flood. Only then was FEMA authorized to come to Whatcom County.

FEMA’s arrival meant that flood victims could begin registering for federal disaster assistance. By Jan. 11, survivors could apply for assistance on household and essential needs. “The Washington Military Department’s Emergency Management Division and FEMA worked together to award $1.4 million in federal grants to individuals and households in Whatcom County,” FEMA said in an email response to InvestigateWest. On the ground, FEMA opened disaster relief centers throughout the county, where Disaster Survivor Assistance teams helped with aid applications. FEMA also issued fact sheets about individual assistance and the importance of flood insurance.

The Whatcom Long Term Recovery Group is a volunteer-based nonprofit that helps coordinate recovery services for families impacted by the flood. That includes a team of local volunteer disaster case managers who help survivors navigate the flood recovery process. They worked closely with FEMA agents, going door-to-door to assess flood damage and help survivors apply for aid, like federal disaster assistance. That includes “grants for temporary housing and home repairs, low-cost loans to cover uninsured property losses and other programs to help individuals and business owners recover from the effects of the disaster,” according to FEMA.

FEMA has several tools to help after a disaster. The Hazard Mitigation Assistance program provides funding for eligible projects that help reduce disaster risk. This larger program includes the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program — which helps rebuild a community after a disaster — and three others: Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities for reducing future disaster risk, Flood Mitigation Assistance to help reduce the risk of flood damage for buildings insured by the National Flood Insurance Program, and a Post-Fire Assistance grant program.

The Individual Assistance Program supports post-disaster recovery for households and essential needs. And Public Assistance helps rebuild damaged infrastructure, like roads and bridges, with various categories and levels.

Lacey De Lange is the Whatcom Long Term Recovery Group’s lead disaster case manager. She currently helps about 600 households with FEMA aid applications and appeals and works closely with regional FEMA agents. According to De Lange, these agents “bent over backward to do anything they could within their rules and regulations to try and get funding for the flood survivors.”

Still, “there’s never enough money,” De Lange said. “People tend to think that FEMA is the savior that will come and help everybody,” she said, adding that “there’s a big gap between what people get and what people need.”

For Snudden, that rings especially true.

Snudden used to work with foster children at the Washington Department of Children, Youth, and Families, but she lost her job during the pandemic. Since November’s flood, she has moved 10 times, paying for hotels out of pocket and even moving back into her flood-damaged home at times. It was not until mid-March that the Whatcom Long Term Recovery Group was able to help put Snudden up in a hotel where she stayed through the end of June.

Although state and federal assistance was available for temporary hotel accommodations, Snudden found Whatcom Long Term Recovery Group’s assistance much easier to navigate. The local recovery group is not “lined with red tape,” she said, and they did not require the amount of documentation that FEMA does. “FEMA made it too complicated,” she said.

For one, FEMA requires survivors “to document how [they] used disaster funds and keep all receipts for at least three years for verification of how [they] spent the money,” according to FEMA guidance.

Still, Snudden managed to apply for FEMA aid and currently receives some rental assistance, including for a storage unit. But there’s a caveat: “I have to pay it first, and then they reimburse me, which is interesting because I don’t have a job,” she said. “I worry about making it for the next storage unit payment, you know, and it just keeps going month after month.”

In the months since the flood, the focus has progressively moved toward long-term recovery.

Whatcom County’s Emergency Management Department and its River and Flood Division are working with FEMA’s Interagency Recovery Coordination group on long-term recovery efforts. FEMA’s coordination efforts help to bridge local, state, and federal governments to work on watershed management, land use planning, the rural agricultural economy and public warning systems in anticipation of future disasters.

A key component of the long-term recovery effort is the state’s decision to offer a buyout and elevation programs — the former allows individuals to volunteer to have their house acquired by the state and removed from the floodway; the latter raises homes to avoid future flood damage. This is done with money allocated by FEMA through its Hazard Mitigation Grant Program.

The goal: getting people out of harm’s way.

Applying for and implementing the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program, however, is “a bureaucratic nightmare,” according to Deborah Johnson, a river and flood engineer from Whatcom County’s Public Works Department. Johnson is actively involved in the county’s long-term recovery efforts.

“People can’t do anything with their home until they are approved for the buyout or elevation,” Johnson said. “When the grant comes through, the message from FEMA basically says, ‘Yes, we’re giving you the money, but you can’t fix anything up until then,’” she said, adding that there is a two- to five-year wait for the buyout process to go through. “And that leaves a lot of people in limbo. Flood survivors are really struggling.”

A data analysis by Columbia Journalism Investigations shows that Whatcom County has endured four major floods in the last 30 years but has received the third-fewest buyouts in the state — only 12. That does not include pending buyouts following the latest flood. Other counties in Washington have benefited from this program, like King County with 60 buyouts in the past 30 years, Skagit County with 82 and Cowlitz County with 132.

In Whatcom County, 2,000 homes reported damage after the flood. According to John Gargett, deputy director of Whatcom County’s Division of Emergency Management, the areas more severely affected by the flood are also places where many people are economically vulnerable, which creates further challenges for moving to safety.

“The first question is: Are these people even in a position to build a new house or move to a different area?” Gargett said. The next question is one of land availability. “We know there aren’t a lot of areas large enough… especially when you’re looking at hundreds of homes that are within a floodway.”

“That suggests that people need to uproot their lives and move to a whole different community,” he said, adding that the state’s housing crisis makes it even more difficult to find safe, affordable places to live.

“Are there FEMA programs for any of this? Frankly, no,” he added. “There are no federal programs that say, ‘Sorry, your house is flooded out, we’ll go build you a new one somewhere else.’”

Still, this home buyout program has become the nation’s go-to strategy to relocate people out of harm’s way after a climate disaster.

The average value of damage to a home affected by the flood is about $30,000 to $35,000 per house, according to Gargett, and the FEMA individual assistance program awards just under $6,000 on average. “Right off the bat, you’re starting off in the hole if you’re a homeowner,” Gargett said.

FEMA recognizes that the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program “is not a simple process,” as stated in its fact sheet. Grant approval requires coordination and agreement between state and local governments and FEMA. Additionally, “it is important to note that many flooded properties don’t qualify for a buyout, funding is limited, and requests for funding may exceed available resources,” according to the same fact sheet.

With the funding from FEMA’s Hazard Mitigation Grant Program, Whatcom County is offering a volunteer-based buyout program, which means individuals with property in harm’s way can sign up to be bought out. As Snudden’s house is directly in the floodway — the space where a river naturally floods — she was first in line to sign up, and is now anxiously waiting for the buyout to be completed.

Things take time. “It could take a year to 18 months just to know if we even got the grant funding. Then there’s a whole process of contracts and appraisals and acquisitions, buyouts, or elevations,” said Johnson, the county engineer.

According to Johnson, it likely will not be until late 2023 that the funding for the first buyouts under the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program will come through, providing long awaited, albeit still limited, financial relief. “But there are people like Maryann Snudden who can’t wait that long,” Johnson said. “Their homes are in harm’s way, they’re living in a trailer, and there isn’t enough funding to help people get through it,” she said.

Snudden, for her part, is adjusting to life in a new travel trailer. She moved into the trailer at the end of June, after the Whatcom Long Term Recovery Group could no longer help displaced individuals stay in hotels.

While the Whatcom Long Term Recovery Group is helping pay for her spot in a trailer park, Snudden is funding the trailer with a loan that she will have to repay with the expected buyout money, which may not arrive until the end of next year.

Still, Snudden is grateful to have a roof over her head and believes that someday her new trailer will feel like home. “This morning, I woke up, got a cup of coffee, went outside, and just sat there for a good hour with my new neighbors — not thinking of the flood, not thinking about why I’m here to begin with,” she said. “This will be a good healing place, I think, to be able to carry on and move forward.”

Alex Lubben of Columbia Journalism Investigations contributed to this report.

InvestigateWest (invw.org) is an independent news nonprofit dedicated to investigative journalism in the Pacific Northwest. Visit invw.org/newsletters to sign up for weekly updates.