Joy can strengthen our resolve, help us unlock creativity, and bolster our resilience. In Fix’s Joy Issue, we explore the importance and power of finding joy in the face of grief, anger, and a changing climate.

Reading the news, it’s easy to feel grim about the future of our planet. Climate anxiety, frustration, and anger are common reactions. Dallas Goldtooth understands that. But he encourages another equally important reaction: joy.

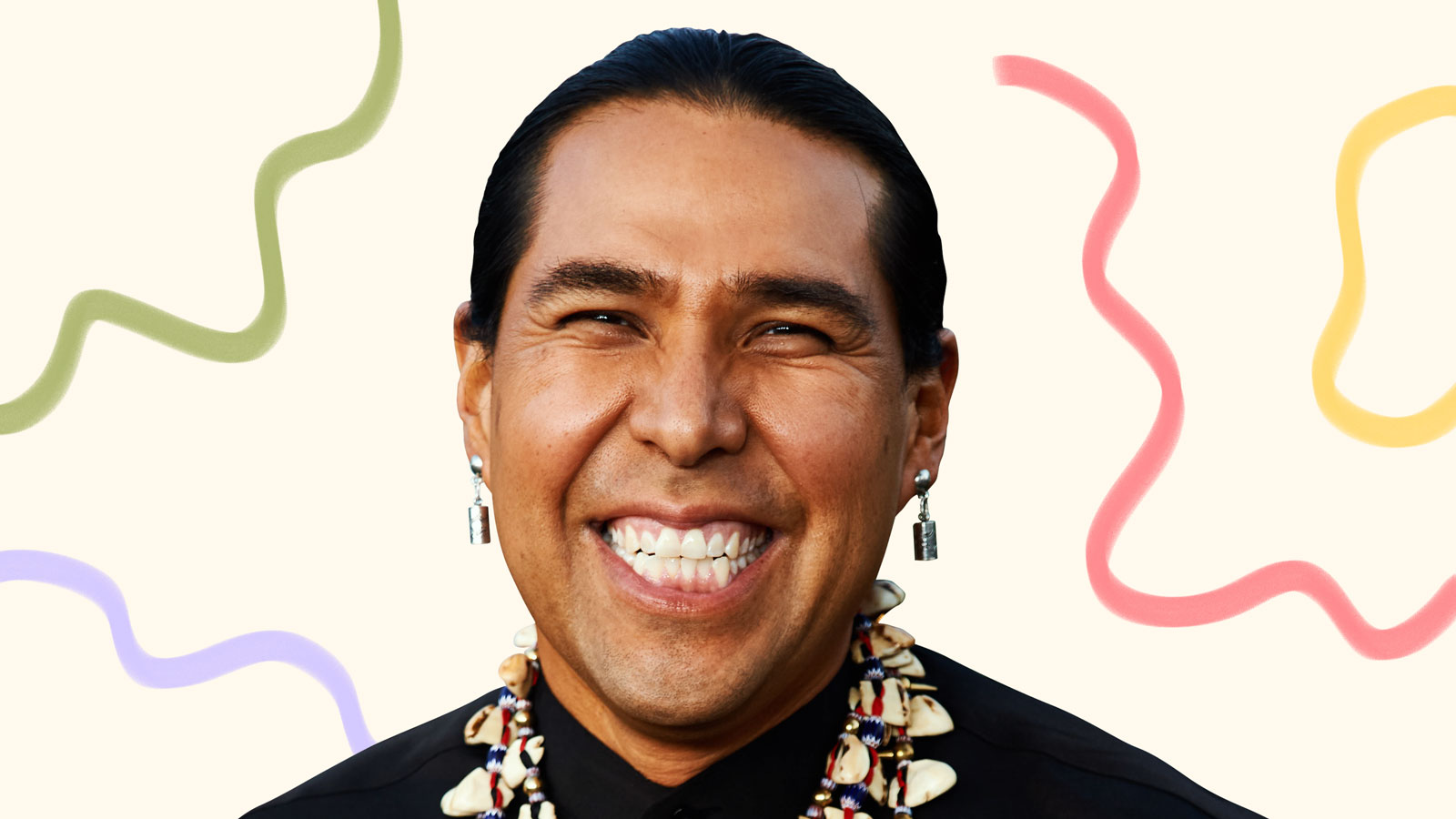

As a “Keep It in the Ground” organizer with the Indigenous Environmental Network and a member of the Dakota and Diné Nations, Goldtooth has been on the front lines, literally and figuratively, of the climate and environmental justice movements. He spent many years working on the successful effort to shut down Keystone XL, and he was fighting the Dakota Access pipeline long before the campaign received widespread attention.

Goldtooth is intimately familiar with the science and statistics behind climate change — he’s written reports on the subject — so he recognizes why people might feel anxious, frustrated, and angry. But the 2017 Grist 50 honoree believes these emotions, though valid, aren’t enough to bring people into the movement, let alone solve our planet’s problems. To Goldtooth, who in addition to being a climate activist is an actor and entertainer, any solution must include a healthy measure of fun.

“It’s easy to fall into this cynicism and negativity, but humor and joy is a way for me to process all of that in a way that’s generative,” he says. “It’s really an outlet for me. My acting, my artistry, is an outlet for me to process my anxieties and frustrations with the world in a way that is generative. It’s building something rather than tearing something down.”

Goldtooth knows a thing or two about humor. Beyond his genuinely hilarious appearance in three episodes of the television series Reservation Dogs, he is a cofounding member of the 1491s, an Indigenous sketch comedy group that uses humor to explore contemporary Native American struggles with stereotypes, racism, tribal politics, and more. His expression of joy isn’t confined to performances, though. Goldtooth once made a point of livestreaming himself gleefully sliding down a hill at Standing Rock, which is just one of many examples of how he brings levity to his activism. He believes others should, too.

“I think there’s nothing more human, nothing [that] speaks more to our ability to process the world around us than our ability to make light of situations no matter how hard or difficult or dark they may be,” he says.

Fix talked to Goldtooth about why he considers joy so essential to activism, why so many activists seem reluctant to embrace it, and how humor can be a liberating force. His comments have been edited for length and clarity.

[Read more: How climate organizers are making joy part of their protest toolkit]

Q. Why is bringing a measure of joy and fun to this work so important to you?

A. It’s so easy for us to get stuck in the pits and fully submerge ourselves with climate anxiety. In order for us to radically imagine a different future, we have to imagine and allow ourselves to experience the joys of this world and see ourselves being happy in the future. That can only manifest if you start now, if you find joy in the moment, and you use love for the land, love for our lives, and love for our people to drive us forward — as opposed to anxiety, anger, and frustration driving that.

I say that, but I also [know that] nothing drives people more than anger. The [idea] that we are pushing ourselves over the edge on this planet is motivating people, but I don’t think we’re going to see lasting change until we find the joy in the future.

Q. That seems so simple, yet so powerful.

A. The key challenge for all of us on this planet, but especially for marginalized communities — whether Black, brown, Indigenous, other communities of color, or poor white communities — is that one of our biggest obstacles is that we have been disenfranchised and not allowed to imagine a future in which we thrive and exist and are satisfied. When we talk about a just transition toward a sustainable society in a new world, what we’re really talking about is allowing ourselves to radically imagine a future in which we exist on our terms. This means that we have to allow ourselves to imagine joy in the future, we have to allow ourselves to imagine that we are happy, that we are fulfilled, and that we are living in a space that is equitable and just. That’s what we work toward, and every aspect of our organizing and artistry should speak to that future that we want to build. That’s what drives me. That’s the core of my work.

When we talk about a just transition toward a sustainable society in a new world, what we’re really talking about is allowing ourselves to radically imagine a future in which we exist on our terms.

— Dallas Goldtooth

Q. How did you come to embrace this perspective?

A. The first time I really became aware of my perspective on things was at the protest at Standing Rock against the Dakota Access Pipeline. I often play the role of communicator in much of my work. I was communicating what was happening, why people were there. When people were broadcasting from the protest, the personas you often saw were angry activists and angry organizers. That’s justifiable anger and rage that you saw, but I noticed that I’m more lighthearted in how I communicate. I chose not to be the angry activist. I found that most appropriate for me.

Q. You talk a bit in Adrienne Maree Brown’s 2019 book Pleasure Activism about the “front” some activists feel they must present, and how they seem reluctant to be seen expressing joy or integrating it into their work. Why do you think that is?

A. I think identities are entirely social constructs. We actively and subconsciously play in and amplify certain identities. Even within the “activist community” or “activist circles,” there is this persona that is assumed that we have to be, and that is the “passionate, angry organizer” who channels their rage to motivate people. That is true because anger and frustration are major motivators. But I think in this movement, there is a reluctance to show our joy because people think they’re not going to be taken seriously. There’s a reluctance to make light of the situation, to use humor in our organizing, to show that we’re also happy. There’s a fear that we will be delegitimized, our struggles will be delegitimized, in some way. But I think we’re changing that.

There’s a growing movement for Black liberation, we’ve seen a great acceptance of Black joy and Black celebration and celebrating Black excellence. The same goes for Indigenous communities. We are claiming that space, saying, “We can still advocate for the protection of our communities and lands, but at the same time we can still express our joy and celebrate our lives.”

Q. Sometimes people are too serious as activists. Do you think there are risks in that?

A. I always get turned off when people are too serious. The camera is on and they’re angry and their brows are furrowed. For me, as an individual, that doesn’t call me in. For some people it does; I can’t say everyone has to be happy. We don’t all have to organize with a smile. But we have to be mindful about what’s calling people in to build collective power, and we can’t ignore the inherent power of using joy and using laughter as a way to heal and build that power. I don’t want to play into, “We don’t like you guys because you’re scary and angry, these folks are more palatable.” Since I’m lighthearted and take this approach, I’m trying to be very cognizant of not undercutting the work of people who choose a different approach.

Q. You’ve talked about using humor and joy as a liberating force for oppressed people, and as a tool for decolonization. Tell me more about that — how is joy a liberating force?

A. In my experience growing up, in the darkest moments, like a funeral, there has always been a key role that humor plays. You’d have individuals in the community, whether it’s the emcee or the spiritual leader, who always tried to make light of the situation, who would always take a moment to make folks laugh in those hard times. As cliché as it sounds, we, as oppressed Native Indigenous people, wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for laughter and humor. I think it really has allowed us to understand the hardships and trauma and oppression that we’ve experienced and are continuing to experience, but it also allows us to respond to that trauma and oppression in a way that reclaims power.

If we can laugh at our oppressors, it takes away the power of our oppressors. If we can laugh at the socioeconomic situation that has been caused by oppression and oppressors and white supremacy, it takes away a certain element of power from those hierarchies.

Q. How can activists and people in frontline communities embrace joy? And why should they?

A. A good example is a group called Gulf South for a Green New Deal and their event, Gulf Gathering for Climate Justice and Joy. That’s literally the name of the event. They [used] that as an organizing moment to educate their communities on false solutions like carbon capture and storage, carbon pipelines, and offshore leasing and drilling. Their angle is, “These are community folks and we want to bring people into this space, but we don’t want to yell at them. We don’t want to be throwing out buzzwords and acronyms. What we’re going to do is celebrate. We’re going to have a festival, we’re going to have music, we’re going to have a celebration, we’re going to express ourselves with smiles while educating folks on the issues, because that’s what really motivates people to build power.” We’re seeing communities claim that and utilize a different way to organize that’s really going in a good way.

Explore more from Fix’s Joy Issue:

- Laughter is the ultimate unifier. Can it work for climate action?

- Why musician Mali Obomsawin traded righteous anger for joyous action

- Your body on joy