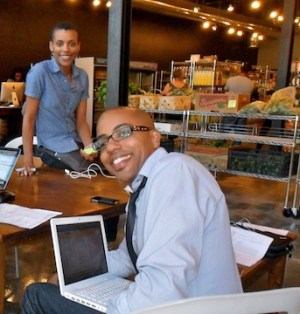

Alison and Alphonzo at The Boxcar Grocer on the day they "soft-launched" the business last fall.

Alison Cross and her older brother Alphonzo saw a vast need for fresh food in the Castleberry Hill neighborhood of Atlanta, where they’d spent time since they were kids. The community, which is adjacent to the Atlanta University Center, had seen both vibrance and decay, and was begging for transformation.

So the siblings decided to fill that need, and hatched a plan to open The Boxcar Grocer, a new food business. Alison, who studied architecture and worked as a video editor, and Alphonzo, with a background in fashion, describe the independent grocery store, which stocks local, organic, whole foods, as being at “the intersection of food justice and high-concept retail.”

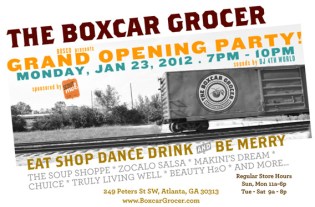

And they’re right; it’s not your average corner store. The market looks modern, with lots of light, stainless steel, and wood. The shop, which had a “soft” opening in late October and celebrated its grand opening on Monday, sits in an area dotted with old railroad warehouses. African Americans own the majority of the storefront businesses. The neighborhood is undergoing a renaissance with small art galleries, graphic design firms, and a tattoo parlor that attract the typical urban mix of students, artists, and free thinkers.

Alison, 36, has also written about the personal inspiration for Boxcar (“This is Our Land“), the socioeconomic challenges of the food movement (“All the Foodies are Rich, All of the Farmers are White, But Some of Us are Still Cookin’“), and its shortcomings (“A Limited Engagement“) on the store’s blog.

I spoke with her recently about her hopes for the family business and the obstacles she and her brother have faced along the way.

Q. Why did you decide to open a corner store in Atlanta?

A. For years we recognized a lack of stores in the area where we could get food we liked when we came to town. The space became vacant in May 2009 but we couldn’t find anyone willing to put in a store. So we researched, wrote a business plan, and started submitting to banks for financing.

In the meantime, I was working at The San Francisco Foundation part-time and part-time at Feldman Architecture, so I was getting this great vision of what could happen when social ideals merge with beautiful design. We felt no one had done that. And there were very few people actually creating something new in terms of for-profit business models for food access. We also figured if we were going to uproot our lives and move away from the Bay Area, it had to be for something extraordinary.

Q. Did you run into any challenges?

A. Unfortunately, the economic crisis meant the process took us two years to complete. Banks flat-out weren’t lending, especially not commercial loans to novices. But we kept charging along. We applied to nine different banks and one foundation and all said no. All we needed was one yes, and that happened in March 2011.

Q. Did you get support from the healthy corner store movement?

A. People we approached in the national food movement didn’t really take us seriously until we actually opened the store. Maybe it’s because we came out of nowhere. We were not involved in politics, nor did we run in foodie circles. We’d meet people at food movement events and when I mentioned opening a store I got the sense that people were dismissive.

Q. What kind of response have you had from local residents?

A. We have had overwhelming support from the community. That’s a wonderful validation because for so long it was this thing rattling around in our heads and on paper. People have been amazingly patient with our mistakes. People are just so grateful to have a grocery store here after all these years. On opening day — which we tried to do quietly to work out the kinks — there was so much buzz about the business we had a line outside the door before we even opened. It was insanity.

Q. Can you tell us about the farmers you work with?

A. Locating local farmers has been a discovery process — we thought we’d be dealing with rural farms — so to find such well-established urban farms as Truly Living Well, Metro Atlanta Urban Farm, HABESHA, and Patchwork City Farms right here in the inner city has been incredible. It’s allowed us to tap their network of supporters and access a knowledge base that is helping us learn about organic farm operations.

I spent last summer riding my bike from farmers’ market to farmers’ market meeting vendors, tasting food, and connecting with the producers.

Q. What about some of the craft products in the store?

A. One couple make these phenomenal pulled pork sandwiches and organic barbecue sauce called The Heat Legend. A product like that speaks to our diverse community. It allows us to meet people where they are with their diet but offer a healthier option that is culturally appropriate. Another producer makes these kale salads with sun-dried tomatoes that people go bananas over. We can barely keep them in stock. It feels good to offer a healthy fast food that people can snack on.

Q. What’s it like running a business with your brother?

A. It’s awesome. We’ve always been close and we’ve always wanted to work together. I’m in awe of his creativity, social nature, and energy. He appreciates the way I dig down in the details and my diligence in seeing things through. We respect each other’s visions and know that we get more done together than we do on our own because of our complementary skills.

Q. Can you give us some background about your own relationship to food?

A. I was a notoriously picky eater as a child. Left to my own devices I’d consume nothing but Frosted Flakes and Kraft macaroni and cheese. Both my parents cooked. My mom made Cajun spiced red snapper, jambalaya, and gumbo, foods influenced by her mother, who was from Louisiana. My dad liked to cook us breakfast. We weren’t really allowed candy or lots of fast food, which was maybe a once-a-month treat. After my dad passed away in 2001, I went to Grenada, West Indies. It was the first time I was really surrounded by utterly fresh food. I was eating fruit right off the trees, vegetables directly from the ground, and seafood caught the same day it ended up on my plate. It was healing and cleansing and opened my eyes to what a difference food can make.

Q. What does food justice mean to you?

A. It means approaching food access as an issue that is not reduced to a socioeconomic determinant. It means adding more faces to the cause so people can identify and desire to be part of a lifestyle shift. If Jay-Z and Kanye can create a lifestyle brand that people in urban and suburban areas aspire to, regardless of their actual income, why can’t we do that with organic food?

We have had family members and friends who are highly educated and in the middle class develop diseases directly related to the food they are eating. I like to tell people that we are not in competition with Whole Foods or Trader Joe’s. We’re in competition with KFC, Burger King, and McDonald’s, who are marketing directly to people like me. The food [access] movement is looking at low-income people and telling them to eat better, but not necessarily including the people who CAN afford to eat better but don’t think it’s important or don’t connect with how it has been presented thus far.

Q. What does the future hold for Boxcar?

A. We have always envisioned Boxcar as a national model. We wanted to be able to create something that would inspire other social entrepreneurs to replicate and hopefully get more healthy corner stores popping up in food deserts to show the demand is there for these businesses. What Alphonzo and I have done is an incredibly risky venture from a financial perspective. But we made a healthy gamble that was deeply rooted in the strength of our education, experience, work ethic, and commitment to seeing the model thrive in different incarnations across the country.

For now, we are focused on building this brand into a strong foundation. We would love Boxcar to be the Walgreen’s of healthy corner stores. We’d like to see at least another five to 10 stores like Boxcar in the next five years.