Fermentation is so hot right now, or, more accurately, the ideal lukewarm temperature that allows the correct microorganisms to thrive and turn your [insert any vegetable you could possibly think of here] into a delicious, salty treat. And while your average Brooklyn pickle-master might have wondered about the tiny creatures who work this magic, there are serious chefs out there who really want to know.

According to The New York Times, ALL of those chefs (OK, at least three of them) have discovered that there’s a friendly lady microbiologist at Harvard named Rachel Dutton who is willing to field all their inquiries about their fermented creations and the communities that make it all happen.

Dutton got into this position through normal scientific inquiry. She was looking, the Times says, for “a village of microbes that could help scientists study how more-complex populations communicate and build microscopic societies.” But it turned out that the best medium in which to raise such villages was cheese:

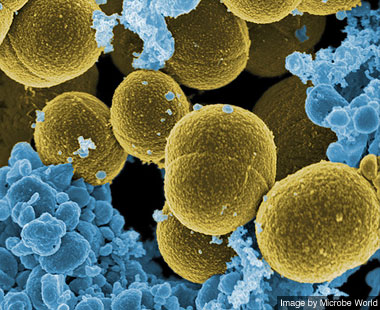

In 2010, she began an ambitious five-year project to sequence, analyze and map the DNA of organisms found on 160 different cheese rinds from around the world. Viewed under a scanning electron microscope, these microbial villages can look very simple or highly diverse — as different as the ecology of Lincoln Center’s well-manicured lawn and that of the High Line before its flourishing weeds were tamed.

Not many scientists are looking at microbes on this small of a scale — the scale on which food-making operates. And it turned out that there were many chefs who had questions about how microbes operate on a food scale. In particular, they wondered how special their favorite, local microbes might be:

Mr. Chang said that he hoped to find signature flavors unique to the East Village that could give “locally grown” a whole new meaning.

“How can we make New York taste New York?” he said. “What makes terroir is the microbes. It’s literally what’s in the air.”

So far, though, the evidence shows that on a microbial level not all local food is so unique. The yeast in Jim Lahey’s sourdough starter, which he has “captured off a cabbage leaf in Tuscany in 1992” was exactly the same as the yeast you’d capture for sourdough anywhere in the world, for instance. And Harold McGee’s “long-lived yogurt culture” turned out to be “a remarkable stable, if not all that surprising, community of Lactobacillus and Streptococcus.”