Twice in the last five years, rising food prices triggered global waves of social unrest. With drought baking U.S. crops, another round of soaring, society-straining price spikes may happen in coming months.

Twice in the last five years, rising food prices triggered global waves of social unrest. With drought baking U.S. crops, another round of soaring, society-straining price spikes may happen in coming months.

According to researchers from the New England Complex Systems Institute (NECSI), commodity speculation — investors betting on food prices — will amplify the drought’s market signals, creating a new food bubble and the crises that follow.

“The drought is clearly going to kick prices up. It already has. What happens when you have speculators is that it goes through the roof,” said NECSI President Yaneer Bar-Yam. “We’ve created an unstable system. Globally, we are very vulnerable.”

The ongoing drought, the United States’ worst since the Dust Bowl, is expected to last until October and will decimate U.S. harvests. America is the world’s largest exporter of corn, wheat, and soy beans; global prices for those commodities have already surged to record levels.

While the United States is relatively insulated from food price increases, people in developing countries, who spend far more of their budgets on food and rely on agricultural imports, are extremely vulnerable. For them, high prices are a catastrophe.

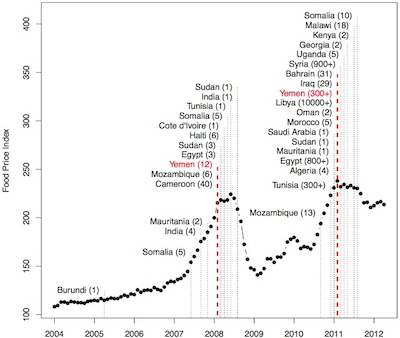

Since 2004, global food prices have slowly but steadily increased, with drastic and socially destabilizing spikes in 2007 and again in 2010. Economists argued over the causes, with blame cast on poor regional harvests, supply shortages caused by converting food crops to biofuels, and — most controversially — speculation.

Until the late 1990s, food markets in the United States were mostly limited to people with direct interests in food prices, such as farmers and crop buyers. Deregulation allowed hedge funds and investment banks to start betting, changing market dynamics and making them prone to sudden, massive fluctuations.

In earlier research, Bar-Yam’s group developed mathematical models of global food market behavior that found biofuels responsible for a slow upward rise in prices, and speculation for the spikes. That model anticipated a new food bubble in early 2013, but couldn’t have foreseen the drought.

In the new analysis, released July 23 on NECSI’s website, Bar-Yam’s group added drought-triggered price increases to the model. With those figures included, the already grim forecast becomes even darker. “The drought may trigger the third massive price spike to occur earlier than otherwise expected, beginning immediately,” wrote the NECSI team.

According to Bar-Yam, excessive speculation acts as an amplifier, exaggerating whatever signal the market receives. Left alone, a highly speculative market would naturally experience boom-and-bust cycles, but this summer’s drought-precipitated surge in food prices will accelerate the next bubble’s formation.

Models are, to be sure, always tricky, but this one does seem to have predictive power.

“The work they are doing on food prices is pathbreaking,” said agricultural economist Peter Timmer of the Center for Global Development, who is familiar with NECSI’s modeling. “I don’t think their empirical model ‘proves’ that biofuels and speculation are the main causes of volatile food prices, but their model is the only one that’s empirically tracked those prices accurately over the last eight years.”

What happens after another bubble is a pressing question, said Bar-Yam. In both 2007 and 2010, massive unrest almost immediately followed food price surges, tracking market behavior with uncanny synchronization. Some Middle East experts say that rising prices even triggered the Arab Spring, providing a spark that ignited long-simmering tensions and resentments [PDF].

While the exact role played by food is difficult to isolate, a new NECSI analysis of the 2008 Yemeni uprising supports the spark hypothesis. In a paper released July 24, NECSI found that the geographical character of violence changed immediately after the price spikes, shifting from ethnically localized to widespread.

FAO food price index between 2004 and 2012, with incidents of social unrest plotted against prices. (Image by NECSI.)

“I think the analysis has merit,” said political geographer Charles Schmitz of Towson University. “The food prices did disturb things. The legitimacy of the government was undermined.”

While some might see the Arab Spring’s catalysis as a positive side effect, food shortages and panicked riots are hardly the most desirable path to social change. To keep prices under control, experts have recommended limiting financial speculation in commodity markets and using biofuel crops for food instead.

“In the short run, USDA needs to figure out a way to remove the mandate on ethanol use from corn,” said Timmer. “If we could free up 20 to 30 percent of the U.S. crop, reduced as it is, it would bring corn prices down very quickly.”

New speculation limits are scheduled to be enacted by year’s end, but drought means that may be too late, said Bar-Yam. In the meantime, the USDA has rebuffed all requests to reduce corn biofuel allotments.

This story was produced by Wired as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

This story was produced by Wired as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.