Oil production and oil refining has killed 77 workers and injured over 7,000 in the last 40 years.Cross-posted from the Center for American Progress. This post was coauthored by Valeri Vasquez, special assistant for energy policy at the Center for American Progress.

Oil production and oil refining has killed 77 workers and injured over 7,000 in the last 40 years.Cross-posted from the Center for American Progress. This post was coauthored by Valeri Vasquez, special assistant for energy policy at the Center for American Progress.

On the one-year anniversary of the BP Deepwater Horizon oil disaster and the Massey coal mine explosion in West Virginia, we are reminded how dangerous our dependence on fossil fuels can be. A large cost of our reliance on these energy sources is the death or injury of workers in these industries. Transitioning to cleaner energy technologies such as solar and wind is safer for workers as well as better for public health, economic competitiveness, and the environment. We can take steps to make fossil fuel industries less dangerous while we transition to cleaner energy.

The toll of fossil fuels on human health and the environment is well documented. But our dependence on fossil fuels exacts a very high price on the people who extract or process these fuels. Every year, some men and women who toil in our nation’s coal mines, natural gas fields, and oil rigs and refineries lose their lives or suffer from major injuries to provide the fossil fuels that drive our economy.

Take April 2010, for example, which proved to be a cruel month for workers in the fossil fuel industry. Twenty-nine coal miners lost their lives at the tragic Massey mine explosion in West Virginia, two miners perished at a western Kentucky mine accident, and 11 workers lost their lives from the BP Deepwater Horizon disaster.

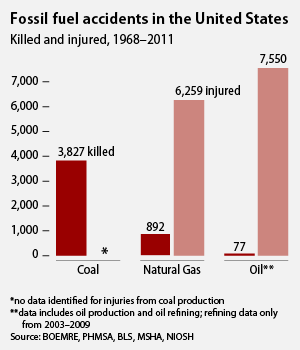

Coal mining is a dangerous profession. Explosions, fires, and collapsed mine shafts have killed at least 3,827 miners since 1968 — not to mention thousands of others who have suffered from pulmonary diseases and other work-related injuries.

To be sure, automated mining equipment and improved safety measures make mining considerably safer than it once was. The mining fatality rate [PDF] has fallen 75 percent since 1970, while the injury rate [PDF] is down by two-thirds since 1973. But it still remains one of America’s most dangerous professions, as the Massey explosion shows.

Oil workers also pay a huge price for our oil use. There have been 77 fatalities and 7,550 injuries at onshore and offshore oil production facilities since 1968, according to our review of Department of Labor data.

Spills related to these accidents totaled 7.5 million barrels of oil and caused billions of dollars of economic and environmental damage. This includes the BP disaster, which spewed 4.2 million barrels into the Gulf of Mexico and according to BP’s own estimate had cost $8 billion in damages by Sept. 2010.

Natural gas, touted as a cleaner and safer alternative to coal and oil, has its perils, too. Natural gas pipeline accidents have resulted in 892 deaths and 6,258 injuries since 1970. According to the Detroit Free Press, there have been 2,554 significant oil and gas pipeline accidents nationwide that caused 161 deaths and 576 injuries in the past decade alone. The 110,700 miles of interstate and intrastate pipelines snaking across the United States makes “accelerating the rehabilitation, repair, and replacement of critical pipeline infrastructure with known integrity risks” crucial to citizen and worker safety.

Many fossil fuel work environments remain unsafe despite thousands of deaths and injuries. In 2005, an explosion at the BP refinery in Texas City, Texas, killed 15 workers and injured 180 others. Since 2003, there have been 20 deaths and 7,400 injuries at oil refineries. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) records before that time are relatively inaccessible.

Many fossil fuel work environments remain unsafe despite thousands of deaths and injuries. In 2005, an explosion at the BP refinery in Texas City, Texas, killed 15 workers and injured 180 others. Since 2003, there have been 20 deaths and 7,400 injuries at oil refineries. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) records before that time are relatively inaccessible.

In the wake of the BP refinery tragedy, the Tony Mazzocchi Center for Health, Safety and Environmental Education conducted a worker safety survey of United Steelworkers-represented oil refineries. The findings were in a 2007 report [PDF] on the “State of Process Safety in the Unionized U.S. Oil Refining Industry.”

The report found that nearly all of the surveyed facilities were vulnerable to similar disasters: “90 percent of the 51 refineries reported the presence of at least one of the three targeted highly hazardous conditions.” The three targeted conditions used in the survey were the “use of atmospheric vents on process units, the siting of trailers and unprotected buildings near high risk process facilities, and the allowance of non-essential personnel in high risk areas.”

But oil refineries, coal mines, and other fossil fuel industries that are chronically out of compliance with health and safety standards cannot be held properly accountable without consistent, up-to-date information about employee fatality, injury, and illness rates. After passage of the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970, the BLS became responsible for collecting data on occupational injuries and illnesses.

Nonetheless, our attempt to gather and compile complete, accurate information for this assessment was difficult because BLS and other agency records were incomplete. This is not an isolated experience, either. A 2006 study by Michigan State University found that the BLS and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s (OSHA) Integrated Management Information System, a national “consolidated database system for collecting, manipulating, maintaining and retrieving” employment-related data, “did not include 61 percent — and with capture-recapture analysis up to 68 percent of the work-related injuries and illnesses that occurred annually in Michigan [alone].”

We therefore recommend that OSHA review its Health and Safety Statistics program to establish best practices for record keeping, determine areas for improvement, and consequently update its database.

OSHA can look to “Governing by the Numbers,” a 2007 Center for American Progress report that assesses the promise and challenges of “data-driven policy making in the information age,” to increase the comprehensiveness and accessibility of its information about fossil fuel industry fatalities and injuries. The report makes three critical recommendations that OSHA and other agencies should adopt:

- Close gaps in knowledge by harnessing new technologies to collect, analyze, and disseminate key data.

- Focus on results by setting quantitative, outcome-focused goals, measuring policy performance, and comparing results among peers.

- Develop systems to ensure data are used to guide policy priorities and solutions.

Accurate data and thorough analysis is impossible, however, without sufficient funding. OSHA received $35 million in the fiscal year 2010 enacted budget to collect and evaluate workplace safety and health statistics. In the newly enacted fiscal year 2011 continuing resolution, $34.9 million was cut, deleting funds for the rest of the fiscal year. Overall, the continuing resolution reduced OSHA’s total budget by $99 million, an 18 percent cut. This includes cuts in federal and state enforcement of workplace safety standards.

To protect fossil fuel and other workers from death and injury, OSHA must have the resources it needs to set and enforce standards and provide compliance assistance and training to aid risky workplaces. More funds for more frequent inspections of fossil fuel and other very hazardous workplaces are also essential. This would increase protection for the men and women in these dangerous fossil fuel industries.

Labor unions also played an essential role to ensure worker safety beginning with the horrible Triangle Shirtwaist Fire in 1911. But successful business efforts to shrink or neuter unions over the past 30 years leave employees more vulnerable to a dangerous workplace.

The Center for Progressive Reform noted last year [PDF] that “the decreasing power of unions to organize and press employers to implement strong health and safety programs” puts oil, refinery, coal, and natural gas employees at risk. With fewer or weaker union officials, workers in these industries must rely more on an underfunded OSHA to set and enforce protection standards that dramatically reduce the occupational hazards they encounter in their daily work.

Finally, the United States must make significant investments in energy efficiency and clean, noncombustible renewable energy sources. These decentralized, less-complex power producers, such as solar panels and wind farms, are much less susceptible to large, catastrophic disasters such as the Massey and BP Deepwater Horizon tragedies. Many of the professions in fossil fuel industries — including manufacturing, plumbing, electrician, and construction — are easily transferable to the cleantech sector.

No workplace can ever be risk free. But efficiency and renewable energy technologies promise fewer worker injuries, illnesses, and deaths while generating power more cleanly and protecting public health. Let the transition begin. In the meantime we should adequately fund OSHA, push for comprehensive, centralized data collection and analysis to hold fossil fuel industries accountable, and strengthen unions. All these steps would go a long way toward protecting fossil fuel workers.