This story is part of Record High, a Grist series examining extreme heat and its impact on how — and where — we live.

This summer was the hottest ever recorded, and 2023 is on track to be the hottest year in history. Next year is likely to be even warmer thanks to a strengthening El Niño, a cyclical weather pattern that contributes to above-average temperatures across much of the globe. The extreme heat has made the consequences of more than a century of reckless reliance on fossil fuels impossible to ignore.

As it gets hotter, more people will succumb to heat-related illnesses. The average number of heat-associated deaths that occur every year in the U.S. rose 95 percent between 2010 and 2022. That data doesn’t include this year’s record-breaking summer. The good news is that heat-related illness is highly treatable. The key is to get the right resources to the right places in time to save lives.

A first-of-its-kind initiative called the Climate Health Equity for Community Clinics Program aims to fight back against the rising tide of heat-associated illnesses in the U.S. by getting resources and training into the hands of doctors and the communities they treat. The program, announced last month by the global health and development nonprofit Americares and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, is the result of a year of research on the climate-related health threats that clinicians across the nation face on a daily basis. Heat, the primary cause of weather-related deaths in the U.S. in 2022, quickly floated to the top of the list of clinicians’ concerns, followed by wildfire smoke. Americares and Harvard, with $2 million in funding from Johnson & Johnson, the multinational pharmaceutical company, partnered with 10 clinics in Florida, Louisiana, and Arizona. The program aims to expand to 100 clinics by 2025.

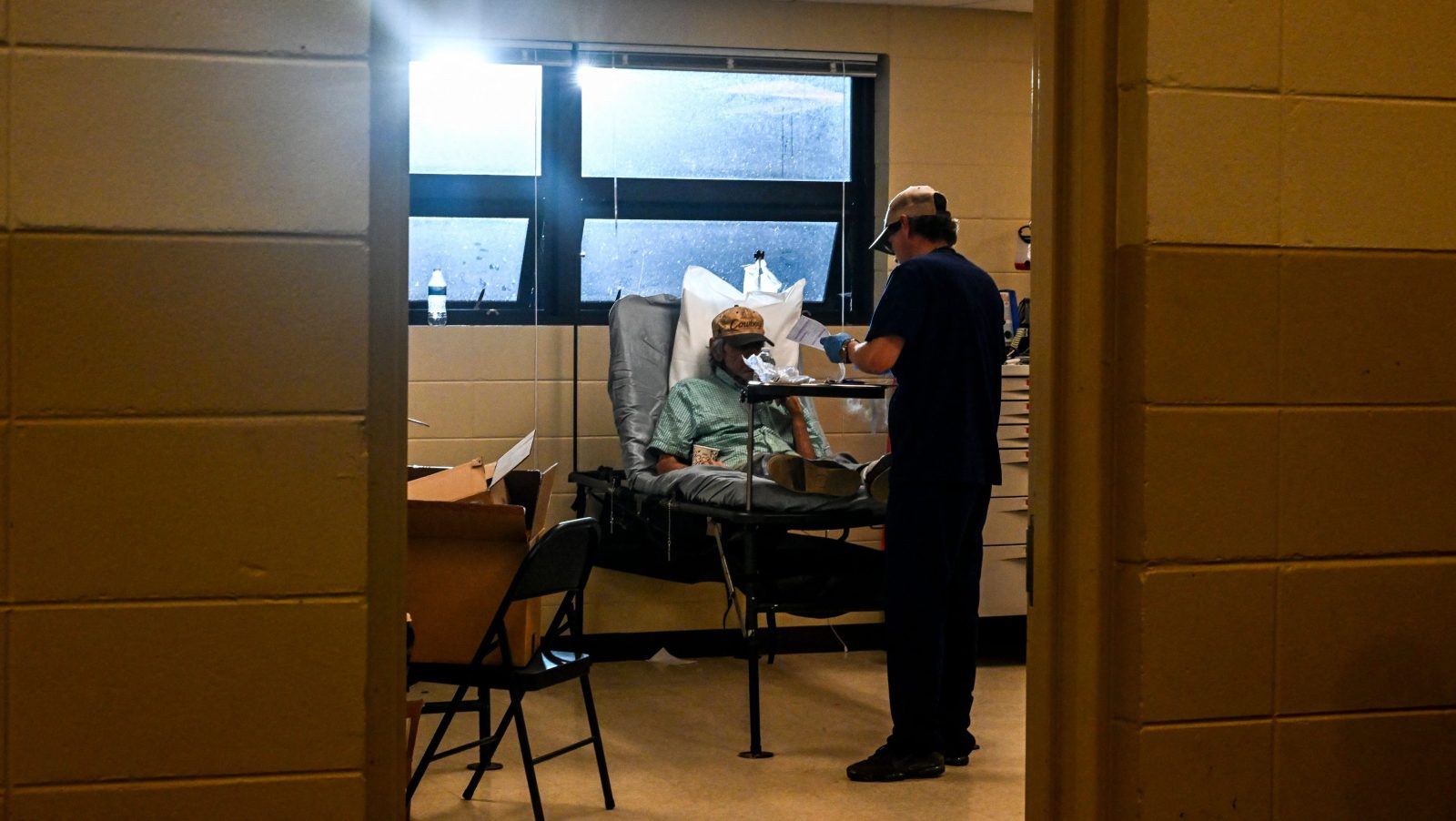

The idea behind the program is to ensure that medical professionals at free clinics and community health centers, which work closely with disadvantaged, uninsured communities, identify which of their patients are most vulnerable to extreme heat and arm them with the tools they need to avoid ending up in the hospital with heat-related illness or heatstroke. Providers at participating clinics will be able to type patient information, symptoms, and relevant environmental factors into an online tool and receive a tailored heat mitigation plan from Americares and Harvard. Clinics in the program will also be alerted when dangerous heat waves are bearing down on their area.

“It’s all about preparedness and how we can help save lives when these heat disasters happen,” said Suzanne Roberts, chief executive officer at the Virginia B. Andes Volunteer Community Clinic in Port Charlotte, Florida. Her clinic, which has served its community since 2008, is one of the first 10 pilot clinics being funded by the new program. “We see our patients coming in with heatstroke, we see our patients coming in with nausea, and they don’t understand that it is related to the heat. We hope to learn the rules of the road so when this happens — and it will continue to happen — we will be prepared.”

Excessive heat erodes human health in a staggeringly wide array of ways. Heat affects our motor functions, appetite, quality of sleep, and our drug and alcohol intake. It puts stress on our bodies and exacerbates underlying conditions such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes. It damages our mental health and affects the medications people take to keep depression at bay. It worsens schizophrenia. It can cause third-degree burns from contact with pavement and hot surfaces. And when people are exposed to high temperatures for too long, heat causes their core temperature to rise. Many people, especially those without access to air conditioning, experience excessive sweating, goosebumps, headaches, dizziness, vomiting, shaking, fainting, and other symptoms of severe heat-related illness. The unluckiest — including more than 1,500 Americans last year — die.

Global health outfits like the World Health Organization and governments have long engaged in heat health action planning to prepare for the health impacts of elevated heat at the national level. Municipalities in the U.S. use this type of planning as well, but community health clinics are rarely looped in. The new program customizes this type of planning for individual clinics and provides recommendations for how the clinics can help their patients navigate heat outside the clinic walls.

The program also aims to bridge divides between clinicians and local public health officials and emergency management departments in order to make sure local resources are directed to the right places. “Clinics often don’t think of themselves as being an important entity when it comes to emergency response broadly,” said Nate Matthews-Trigg, associate director of climate and disaster resilience at Americares and the head of the project. “But now as we’re seeing more and more extreme weather related to climate change, they’re finding themselves on the front lines.”

For example, many cities set up cooling centers during heat waves to help keep residents without air conditioners cool, but those cooling centers often sit empty, even as hospitals fill up with patients suffering from heatstroke. That’s because a lot of people either don’t know about the cooling centers or don’t have a way to get to them. Many clinics, particularly in underserved areas, have contracts with non-emergency patient transportation — vans and buses paid for by the city or funded by the clinics to help patients get to their medical appointments. “Can they leverage those relationships to help their patients get to cooling centers?” Matthews-Triggs asked. That’s one of the interventions the program plans to try out over the next couple of years. Clinicians will also work with emergency managers to make sure air-conditioning units are being provided to those who need them most. Additionally, participating clinicians will teach community aid workers, like soup kitchen volunteers, to be able to identify symptoms of heat-related illness.

The Climate Health Equity for Community Clinics Program, with just 10 clinics in three states, is tiny right now. There are tens of thousands of health clinics across the U.S. with varying degrees of preparedness for the health impacts of climate change. Even when the program expands to its expected 100 clinics, its efforts will just be a drop in the bucket. Heat-related illnesses pose a threat to communities in every state in the nation — hundreds of millions of Americans. But experts not involved in the program told Grist that the initiative seems promising.

“Anything that can help better identify who is in need of what and where the resources are, and connect those two things, is going to be helpful in managing the response to any sort of crisis event,” said Samantha Penta, an associate professor in the department of emergency management and homeland security at the University of Albany. Clinicians, who are often seen as trustworthy by the community, are well-positioned to coordinate resources and bridge gaps between local officials and aid groups once the heat has descended. Americares and Harvard plan to use the information they gather between now and 2025 to bolster community-level responses to extreme heat, first in the U.S. and later in middle- and low-income countries around the globe.

“If they find this is a useful resource, then it’s probably something that we want to see spread,” Penta said. “Everything has to start somewhere.”