At 5 a.m. on December 4, 2017, Jesse Merrick got a text from his roommate. “Hoping your family is OK,” he remembers reading when he woke up. The Thomas Fire had just broken out in Southern California and was quickly growing into a nearly 300,000-acre behemoth. Jesse frantically tried to reach his relatives in Ventura. When he finally got hold of his mom, she was broken. “She answers the phone and she’s crying hysterically,” Jesse said. “She says, ‘It’s gone. It’s all gone.’”

The Merricks’ ranch-style home, with most of Jesse’s childhood stuff in it, burned down that day. A week after the fire, he flew out to help his mom salvage what was left. They spent days sifting through the rubble. Jesse, a former college football player, took on the strenuous task of sorting through the wreckage in the deep, charcoaled hull of their basement. The whole family wore masks to protect their lungs from the dust and gloves to shield their hands from sharp objects. But it wasn’t protection enough from the danger lurking in the dirt.

Smoke and dust blow off the burned remnants of Jesse Merrick’s family’s home after the 2017 Thomas Fire. Photos courtesy of Jesse Merrick.

Three weeks later, Jesse had to fly back home to Alabama, where he was working as a sportscaster. He was in charge of covering the annual Sugar Bowl college football game in New Orleans — a big opportunity. But when he got there, something didn’t feel right. “I felt like I had gotten hit by a bus,” he said. Jesse chalked it up to jet lag and pushed through with the broadcast. But his symptoms didn’t subside. Instead, they got much, much worse. Within a couple of days, he was coughing and running a low-grade fever. A rash had appeared on his upper torso. “I remember being miserable,” he said. “I wasn’t sleeping.” Once the rash started moving up his neck, about four days after he first started feeling sick, Jesse knew he had to get to an urgent care clinic.

That was the first of many doctor’s visits. For a month, Jesse’s symptoms worsened. Giant welts appeared around his joints like someone had whacked him all over with a baseball bat. He developed pneumonia, which made everything hurt, even breathing. Walking was painful. “It felt like someone was stabbing the bottom of my feet with knives,” Jesse recalled.

By the time his primary care doctor discovered a six-centimeter mass in his lung, Jesse was starting to think that whatever disease he had might actually end up killing him. He was scheduled for a biopsy and a spinal tap — last-ditch efforts to find the source of his illness. But on the morning of the procedures, a team of infectious disease specialists appeared in his hospital room. “It was like I was on an episode of House or something,” Jesse said, chuckling. The biopsy and the spinal tap were suddenly irrelevant. The specialists were able to give him what his regular doctor couldn’t: a diagnosis.

Jesse had a disease called Valley fever. It’s caused by one of two strains of a fungus called Coccidioides, Cocci for short, that thrive in soils in California and the desert Southwest. The mass in his lung wasn’t cancer, it was a fungal ball — a glob of fungal hyphae, or mushroom filaments, and mucus. The infectious disease specialists started him on an intravenous drip of fluconazole, an antifungal medication. “Instantly, I started feeling better,” Jesse said.

Jesse got lucky that day. The infectious disease experts were in the right place at the right time. Some 60 percent of Valley fever cases produce no symptoms or mild symptoms that most patients confuse with the flu or a common cold. But 30 percent of those infected develop a moderate illness that requires medical care, like what Jesse had. And another 10 percent have severe infections — the disseminated form of the disease, when the fungus spreads beyond the lungs into other parts of the body. Those cases can be fatal.

Doctors don’t know why certain people experience no symptoms while others wind up in the emergency room. But they do know that pregnant people, the immunocompromised, African Americans, and Filipinos are especially at risk. And they also know that Cocci is a generalist. Any person, dog, or other mammal who breathes in air laced with the fungal spores is at risk of developing the disease, which kills roughly 200 people in the U.S. every year. No vaccine currently exists, and the antifungal treatment is a bandaid, not a cure.

Jesse’s difficulty getting a fast and accurate diagnosis isn’t an isolated incident. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the CDC, estimates that some 150,000 cases of Valley fever go undiagnosed every year, though that’s likely just the tip of the iceberg, doctors and epidemiologists told Grist. The disease is only endemic to certain geographic areas and it’s technically considered an “emerging illness,” even though doctors have been finding it in their patients for more than a century, because cases have been sharply rising in recent years. In some places, astronomically so. Valley fever cases in the U.S. increased by 32 percent between 2016 and 2018, according to the CDC. One study determined that cases in California rose 800 percent between 2000 and 2018.

In most states where the disease is endemic, public health departments have been slow to grasp and advertise the breadth and potential impact of the illness, experts say, and the federal government could be doing more to fund research into a cure or vaccine for the infection. To date, there’s only been one multi-center, prospective comparative trial for the treatment of Valley fever. And, more troubling, researchers haven’t pinned down exactly what’s behind the rise in cases or how to stop it. One thing is nearly certain, though: Climate change plays a role.

In 1892, a medical student in Buenos Aires named Alejandro Posadas met an Argentinian soldier who was seeking treatment for a dermatological problem. Posadas documented a fungal-like mass on the patient’s right cheek. Over the course of the next seven years, the soldier experienced worsening skin lesions and fever, and eventually died. His story is the first case of disseminated Coccidioidomycosis on record.

Around the same time, a manual laborer in the San Joaquin Valley walked into a hospital in San Francisco with skin lesions that looked a lot like the lesions on the Buenos Aires patient. The methods doctors used in San Francisco to treat the patient were barbaric. They cut chunks out of his face and treated the lesions with oil of turpentine, carbolic acid, and scrubbed his raw skin with a bichloride solution. They only succeeded in torturing their patient, who eventually died.

Over the next few decades, as more people got sick with Coccidioidomycosis and died, doctors figured out that the organism causing this disease often entered victims through the lungs. In 1929, a 26-year-old medical student at Stanford University Medical School cut open a dried Coccidioides culture and accidentally breathed in its spores. Nine days later, he was bedridden. But this time, the patient’s conditions improved and he eventually recovered. His illness would soon help doctors make a crucial connection.

It was only a few years later that the Kern County Department of Public Health in California began investigating the causes of a common disorder called “San Joaquin fever,” “Desert fever,” or “Valley fever,” which got its name from the state’s Central Valley, where the disease was prevalent. As doctors reviewed evidence from Kern County, they noticed commonalities between cases of Valley fever there and the disease the Stanford student experienced. Valley fever, they hypothesized, represented the Coccidioidomycosis infection.

Over the following decades, researchers would discover some important truths about Valley fever. They found that it is endemic to certain areas of the world, that the fungus that causes the disease lives in soil, that a majority of people infected by it are asymptomatic, and, crucially, that weather patterns and seasonal climate conditions have an effect on the prevalence of Coccidioides.

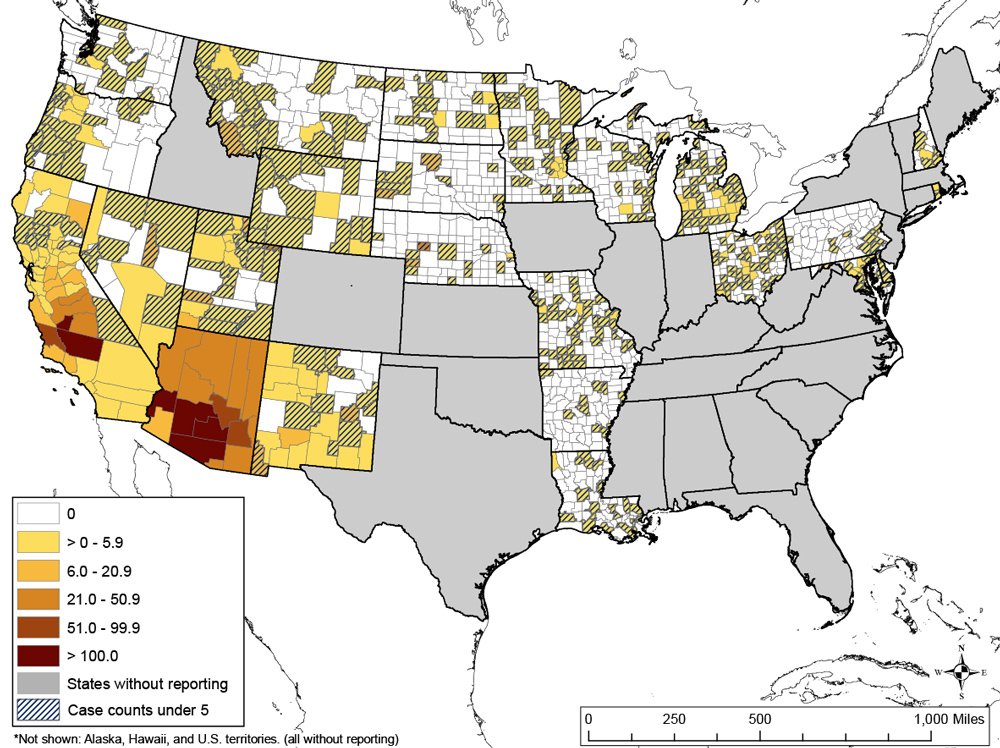

A few years ago, Morgan Gorris, an Earth systems scientist at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, decided to investigate an important question: What makes a place hospitable to Cocci? She soon discovered that the fungus thrives in a set of specific conditions. U.S. counties that are endemic to Valley fever have an average annual temperature above 50 degrees Fahrenheit and get under 600 millimeters of rain a year. “Essentially, they were hot and dry counties,” Gorris told Grist. She stuck the geographic areas that met those parameters on a map and overlaid them with CDC estimates on where Cocci grows. Sure enough, the counties, which stretch from West Texas through the Southwest and up into California (with a small patch in Washington State) matched up.

But then Gorris took her analysis a step further. She decided to look at what would happen to Valley fever under a high-emissions climate change scenario. In other words, whether the disease would spread if humans continued emitting greenhouse gases business-as-usual. “Once I did that, I found that by the end of the 21st century, much of the western U.S. could become endemic to Valley fever,” she said. “Our endemic area could expand as far north as the U.S.-Canada border.”

There’s reason to believe this Cocci expansion could be happening already, Bridget Barker, a researcher at Northern Arizona University, told Grist. Parts of Utah, Washington state, and Northern Arizona have all had Valley fever outbreaks recently. “That’s concerning to us because, yes, it would indicate that it’s happening right now,” Barker said. “If we look at the overlap with soil temperatures, we do really see that Cocci seems to be somewhat restricted by freezing.” Barker is still working on determining what the soil temperature threshold for the Cocci fungus is. But, in general, the fact that more and more of the U.S. could soon have conditions ripe for Cocci proliferation, she said, is worrying.

There is a massive economic burden associated with the potential expansion of Valley fever into new areas. Gorris conducted a separate analysis based on future warming scenarios and found that, by the end of the century, the average total annual cost of Valley fever infections could rise to $18.5 billion per year, up from $3.9 billion today.

Gorris’ research investigates how and where Cocci might move as the climate warms. But what’s behind the rise in cases where Cocci is already well-established, like in Ventura, where Jesse Merrick’s family home burnt down, is still an area of investigation.

Jesse thinks the cause of his Valley fever infection is obvious. “I clearly see a correlation between the fires and Valley fever,” he told Grist. But scientists aren’t exactly sure what environmental factors drive Cocci transmission, and neither are public officials.

In a December 2018 bulletin, Ventura County Health Officer Robert Levin cast doubt on the connection between Cocci and wildfires. “As Health Officer for Ventura County, I don’t see a clear-cut connection between wildfires and Cocci infections,” he said, noting that only one of the 4,000 firefighters who worked on the Thomas Fire in 2017 got Valley fever. Jennifer Head, a doctoral student at the University of California, Berkeley, who works for a lab studying the effects of wildfires on Valley fever, hasn’t seen much evidence backing up such a connection either. “The media talks a lot about wildfires and Valley fever and the general speculation is that wildfires will increase Valley fever,” she said. But the closest thing Head could find linking the two was a non-peer-reviewed abstract — a scientific summary — that wasn’t attached to a larger paper.

What experts do know, however, is that disturbing soil, especially soil that hasn’t been touched in a long time, in areas that are endemic to Cocci tends to send the dangerous fungal spores swirling into the air and, inevitably, people’s lungs. That’s why wildland firefighters tend to get Valley fever, not necessarily from the flames themselves, but from digging line breaks in the soil to help contain fires. Construction sites are responsible for a huge quantity of Valley fever infections for the same reason.

And the fact that researchers haven’t been able to find a link between wildfires and Cocci doesn’t necessarily mean that Jesse’s theory about how he contracted his illness is incorrect. Researchers have documented the Cocci fungi living in many parts of California. But the fungus isn’t evenly distributed throughout the areas where it grows. Think of a mountainside covered in wildflowers, John Galgiani, director of the Valley Fever Center for Excellence in Arizona, told Grist. Wildflowers grow in swaths across mountains, not evenly saturated throughout the landscape. Coccidioides similarly grows in flushes across the landscape. That means a wildfire that breaks out in an area that is endemic to Valley fever won’t necessarily encounter a vein of Cocci fungi.

“If a fire happened to be where there was Valley fever fungus in the soil, then that would be a risk,” Galgiani said. “But that’s a little different statement than all wildfires cause Valley fever.”

And no research has been published, yet, on the possibility of Cocci being spread to humans in wildfire smoke, though plenty of research has been conducted on the effects of smoke on human respiratory systems. “The potential for human pathogens to be spread in wildfire smoke has been ignored by those working on the health impacts of wildfire smoke just completely,” Jason Smith, a professor of forest pathology at the University of Florida, told Grist. He’s working with a group of researchers across the U.S. on a study that seeks to determine whether Cocci spores and a host of other fungal pathogens can travel via wildfire smoke. The portion of his research that focuses on Cocci is still in its early stages, but previous studies he’s worked on have demonstrated that fungal spores can indeed travel quite far in smoke. “There’s just no reason why Cocci would be immune from that,” he said. “Now humans getting sick from it? More so than they do under ambient conditions? That’s the difficult part — determining that that’s occurring.”

The connection between climatic changes and Valley fever is a bit clearer. Researchers speculate that a pattern of intense drought followed by intense rain may be driving the rise in Valley fever cases. When there’s a prolonged drought, the fungus in the soil tends to dry up and die. But no drought goes on forever — at least not in most parts of the U.S. When the rains eventually come back, the fungus flourishes. Then when the next drought hits and soils and the fungus dry out again, it is easy for wind — or a firefighter’s shovel or a hiker’s boot — to disturb and disseminate the abundant rain-spurred spores.

“The big issue is drought, it’s dryness,” Julie Parsonnet, a specialist in adult infectious diseases at Stanford University, told Grist. “And after a period of rain it’s even worse.” Parsonnet sees the real-world consequences of that dry-wet cycle at Stanford, where she works at a referral center that sees patients with even worse Valley fever than Jesse had — the really bad cases. “We see really terrible disease with the fungus affecting their brains and their bones,” she said. “In terms of how severe it is and the lifelong requirement for some of these people for treatment, it’s worrisome. We don’t want to see it. It would be a bad thing to see more Cocci than we have already.”

Parsonnet has been at Stanford for three decades, and over that time, she’s not only seen more Valley fever cases, but more severe cases. “In the last few years, I’ve been taking care of three or four Valley fever patients at any given time,” she said. “In the first 20 years I was here, I saw maybe one or two total.”

Decades have come and gone since researchers first connected the dots between the Cocci fungus and Valley fever. A growing body of research supports the idea that climate change is now making this disease worse. Yet public awareness of what Valley fever is and how it works, in addition to the medical know-how to tackle this disease, is still lacking, even in states where Valley fever is prevalent. “You’d be surprised by how delayed the diagnosis is,” Galgiani, from the Valley Fever Center for Excellence in Arizona, told Grist. “And that’s the patients who get diagnosed.”

Part of the blame lies in the way doctors practice medicine. An accurate Valley fever diagnosis may hinge on no more than where the attending physician went to medical school. “Many of the doctors who practice here learn medicine where the disease doesn’t exist, like in New York, for example,” Galgiani said. Another issue is the length of time it takes for the Valley fever blood test to come back from the lab — typically around two weeks. Clinicians in an outpatient setting like an urgent care clinic or emergency room are often reluctant to order a test that won’t come back before the patient goes home. “If the test comes back positive, they have to find the patient and tell them, ‘There’s a problem here.’ It’s not what they like to do,” Galgiani said.

When doctors do order a Valley fever blood test, the results of that test aren’t guaranteed to be accurate. One in five Valley fever tests produce a false negative, said Steven Oscherwitz, an infectious disease doctor at Southern Arizona Infectious Disease Specialists. “It can be kind of silent and hard to diagnose because our tests just aren’t that great,” he said.

But part of the blame also lies with states and the way their public health departments prioritize diseases. Laurence Mirels, an infectious disease specialist in San Jose, California, who is affiliated with the California Institute for Medical Research, said that Valley fever has long languished behind HIV, West Nile Virus, typhoid fever, tuberculosis, and other communicable or vector-borne diseases in states’ list of public health priorities. That’s despite the fact that the disease’s morbidity rate in the regions where it is endemic is comparable to polio, measles, and chicken pox before those diseases were stymied by vaccines.

“The things that public health departments tend to focus on are things that can be transmitted and can increase exponentially if the source isn’t dealt with,” Mirels said. “Cocci isn’t quite that way.” The disease can’t be passed on from person to person.

“It’s not like COVID where you’re well one day and dead the next week,” Parsonnet, from Stanford University, said. “If you have bad Cocci it’ll drag on for years and maybe even decades. And for that reason it makes less of a splash.”

Out of all the states in the U.S. that are endemic to Valley fever, Arizona is best equipped to handle the rise in Cocci cases. The state public health department keeps close tabs on Valley fever and regularly reports cases to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Valley Fever Center for Excellence, housed within the University of Arizona, helps facilitate collaboration between doctors and researchers across multiple counties within Arizona and develops strategies for diagnosing and treating Valley fever. The Arizona Department of Health Services, the state’s public health department, has spent time and resources trying to raise Valley fever awareness among Arizonans.

There’s a reason Arizona is ahead of the curve. It has the highest rates of Valley fever in the nation. “Arizona is a special case because it’s hard for them to ignore it,” Galgiani said. “It’s the second or third most frequently reported public health disease in the state. That’s not the case anywhere else in the country.” Other states like Utah, Texas, New Mexico, and Washington are also clocking rising rates of Valley fever, but it may be some time before the disease poses a big enough risk to residents that public health departments in those states start dedicating significant time and resources to it. West Texas, for example, is an “intensely endemic” region, Galgiani said. But the Texas Department of State Health Services doesn’t even report Valley fever cases to the CDC yet.

“I think it’ll probably take expanding numbers to get people’s attention to make this a higher priority among everything else that needs attention,” Galgiani said.

There’s evidence that that is already starting to happen in California, where Valley fever is becoming an increasingly serious public health threat. In an email to Grist, a spokesperson for the California Department of Public Health noted that Valley fever cases in the state nearly tripled between 2015 and 2019, from roughly 3,000 cases to 9,000. “The annual number of reported cases has increased significantly since 2010,” the spokesperson said. The Department of Public Health got funding from the CDC in 2012 to hire an epidemiologist to study fungal diseases in the state, and it launched a $2 million Valley fever awareness campaign in 2018. “I think there is a kind of an awakening of the understanding that this is a problem,” Mirels said.

But even in Arizona, the state at the head of the pack, more could be done to alert residents to the dangers posed by Valley fever. Some residents suspect optics may be trumping public safety. “Imagine that you put ads up that say, ‘You’re going to catch this terrible disease if you come here, look at what it does to people,” Oscherwitz said. “They’re not going to really want to do that because tourism would be affected and nobody is going to come here who hears that.”

“I think there’s been reluctance by politicians to advertise this disease because it might deter people from coming here,” said Mark Johnson, President of the Tortolita Alliance, a conservancy group in Arizona that advocates for better Valley fever awareness. “But that is not the important thing. They should be doing everything in their power to make people aware of the disease.” Johnson, who contracted valley fever last year after retiring to Arizona, argued that if the state was really dedicated to protecting Arizonans from Valley fever, it would run advertisements on TV, put up signs up airports, and send out brochures, especially to new residents.

Valley fever on its own is a formidable and expensive illness to contend with. But it’s not the only fungal pathogen lurking beneath our feet. There are three main types of fungi that cause lung infections in humans in the U.S., including Cocci. Histoplasmosis and blastomycosis also pose risks to humans. It’s possible that the same environmental conditions that may be helping Cocci spread into new areas and become more prevalent are also motivating those fungi. Researchers can’t say for sure whether that’s happening yet, but it’s something they’re working on.

“I can’t really speak to what those predictions might be,” Barker, from Northern Arizona University, said. “But my colleagues have noticed similar trends where there’s an increase in reported disease.”

And another wrinkle: There aren’t nearly enough people studying these pathogens. Every time a human fungal pathogen researcher retires, the field grows smaller. “We’re behind all of these other groups,” Barker said. “We’re behind the bacteriologists and the virologists in terms of our understanding of some of these ecological principles driving distribution of these organisms and what might cause them to emerge in human populations.”

For most of the rest of us, the pathogens hiding in the ground aren’t much of a consideration at all. That applies to Jesse Merrick, too. For him, Valley fever is a distant, if terrible, memory now. He doesn’t let it stop him from doing the things he wants to do. He still goes on hikes and visits his mom in California. And he recently moved to Las Vegas, Nevada, an area that is endemic to Valley fever. “It’s in the back of my head but nothing where it’s something I think about daily or anything like that,” he said.

It may only be a matter of time before we start thinking about fungus more often, Barker said. “I honestly think that the fungal pathogens are going to be a huge problem for us going forward.”