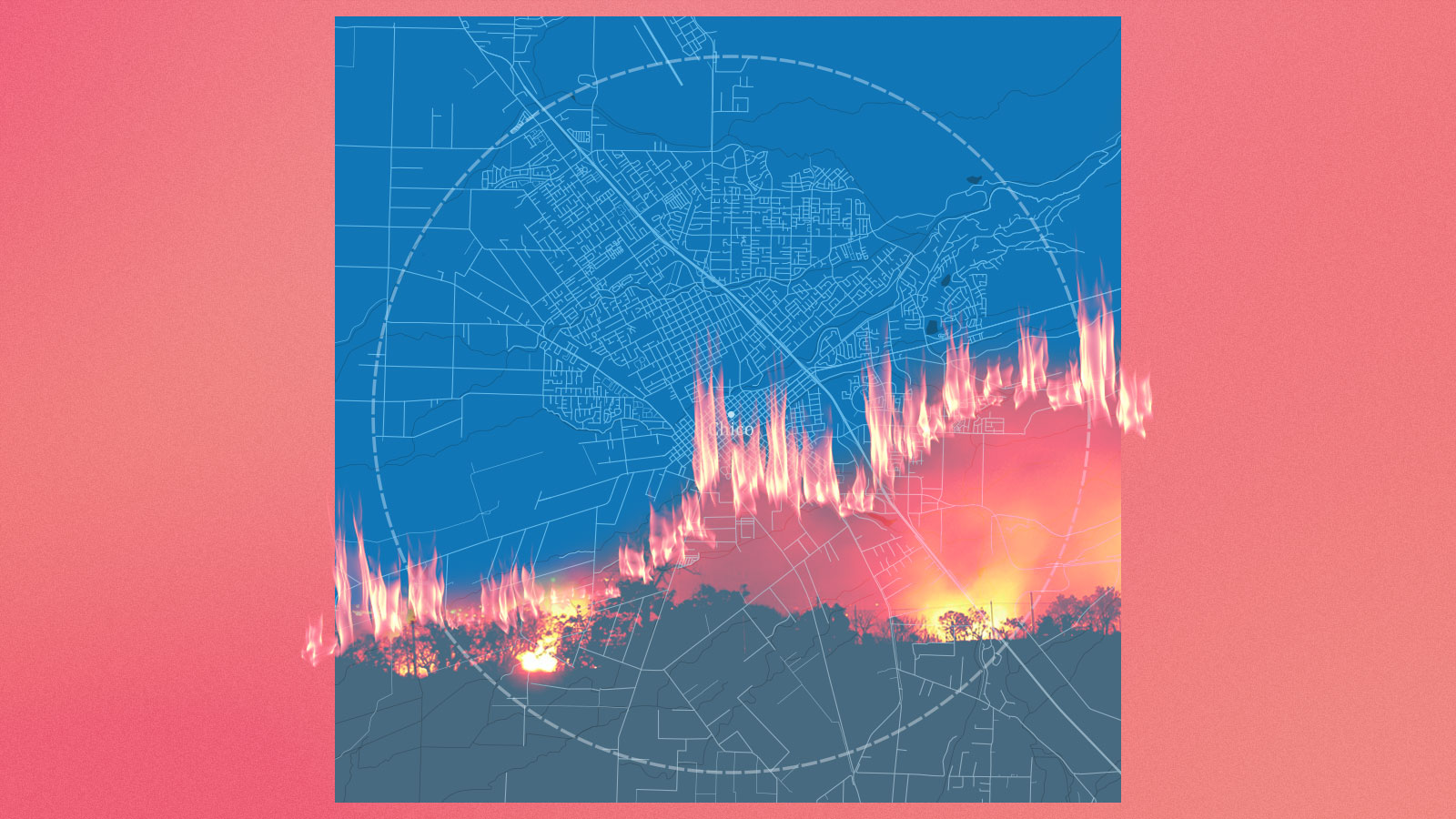

Chico, California, needs housing. The booming city of just over 100,000 issues just a few hundred building permits every year, and it’s rare to see more than a few dozen homes on the market at any given time. Housing costs have risen by double digits since 2018, and homelessness has spiked.

A new development on the outskirts of town, however, promises almost 3,000 new homes: single-family buildings, multifamily apartments, and “residential cottages,” plus a dense and walkable commercial district. Containing hundreds of acres of open meadows, oak forests, streams, and trails, it was designed with the belief that “places for people to live and work can exist in harmony with nature” — the very reason many people moved to Northern California in the first place.

There’s just one problem: Four years ago, a wildfire ignited in the Sierra Nevada foothills that shadow the meadow where the development will lie. The Camp Fire incinerated thousands of buildings, killed 85 people, and roared down the hills toward Chico. It stopped right in the middle of the meadow. Another wildfire almost reached the meadow ten years earlier, and another one a few years before that.

For two years, Chico’s leaders have been debating whether or not to let the housing development, which is called Valley’s Edge, move forward. On one side are the developer and a number of civic organizations, who claim the development will help grow the city’s economy and alleviate a dire housing crisis. On the other are a group of conservationists and anti-development advocates who say the risk of wildfire in the area is too great, and that new housing should be built elsewhere. It will be up to the Chico city council to decide between the two sides.

The wildfires that have raged across the U.S. West over the past decade have exposed new dangers in the area known as the wildland-urban interface, or WUI, the vulnerable territory that sits between developed residential areas and dense, flammable forests. These areas have long been considered some of the most desirable places to build, since they offer natural beauty and distance from urban congestion, plus land that is cheap relative to cities like San Francisco and Los Angeles. But they are also the most vulnerable to wildfire.

City governments across the region are wrestling with questions about whether and how to shift new housing development away from these areas. At the same time, opponents of development are using fire risk as a justification to cancel even projects that are designed to be resilient to fire.

Bill Brouhard, the real estate developer behind Valley’s Edge, has been working on the project for more than 15 years, even before wildfires became a major political issue in Northern California. But even during the Camp Fire, as he watched flames race to the site, he didn’t waver in his resolve to get it done.

“I was out there standing at the edge with residents as the area was burning,” he told Grist. When Brouhard imagined the wildfire racing toward his finished subdivision, he envisioned a series of firebreaks stopping the blaze in its tracks before it reached any homes. “The condition that was happening would be a mile away from the homes, and they wouldn’t be threatened,” he said.

Brouhard added that the development itself would act as a natural firebreak for the rest of the city, thanks to ample parks and trails outfitted with fire-resistant vegetation and pavement. By building Valley’s Edge, he said, “we’re reducing the risk of wildfire to the existing residents of Chico, not increasing it.”

To be sure, Valley’s Edge is far from a cookie-cutter planned community. The east side of the development features rambling open space, and the highest-density housing will be farthest away from the fire-prone hills. The development will be built in compliance with the latest California fire construction regulations and will be an accredited member of the Firewise program, a nationwide initiative designed to promote fire-safe building practices. There will be wide roads to accommodate evacuating cars, plus reservoirs to provide fire trucks with water and trails to serve as firebreaks; Brouhard also plans to clear all the flammable pines from the area and leave only the hardy oaks.

In a notable concession to fire risk, Valley’s Edge scrapped an original plan for a residential neighborhood at the far eastern end of the project, which would have sat right next to the only road out of Paradise, the town destroyed by the 2018 Camp Fire. There were concerns that the added congestion might lead to backups on the road during evacuation events, with deadly results.

Conservation advocates and anti-development activists in the Chico area say that’s nowhere near enough to make the development safe.

“Any structures that are built there, they would serve as fuel for the fire to burn the existing developments to the west,” said Grace Marvin, an activist who organizes with the area’s Sierra Club chapter and a local group called Smart Growth Advocates that is advocating against Valley’s Edge. “In terms of the fire, I don’t know how much they can do about it.”

Indeed, the Valley’s Edge site occupies land that Cal Fire, the state fire agency, classifies as facing “moderate” fire risk, and it is surrounded by areas that the state deems part of the wildland-urban interface. Officials have periodically conducted prescribed burns in the area to clear away flammable vegetation. Other developments in the area have had close shaves with fire before: When the Camp Fire blew into the valley in 2018, it burned the very last house in a development just north of the Valley’s Edge site, then stopped short of spreading further.

Molly Mowery, an urban planner who has consulted with cities on how to design for fire resilience, told Grist that it’s possible to build safe developments in a city like Chico, but everything depends on the details.

“It’s not to say we can’t live in these places, because so much of the West is wildfire-prone,” she said. “We can’t move out of the WUI — the WUI will be there. It’s just: How do we live in the WUI?” Mowery cited the need to clear flammable vegetation from around dense housing areas, bury power lines so they can’t spark up, and ensure that houses are built with fire-resistant walls and windows — all things that Brouhard plans to do in Valley’s Edge.

Brouhard and his opponents may disagree about the vulnerability of the development to wildfires, but they also disagree about a more fundamental question over what kind of housing Chico should build. Marvin thinks the city should prioritize dense, affordable construction on land in the city center, rather than large suburban-style projects such as Valley’s Edge.

“What we’d like to see is affordable infill development in the downtown area, as well as frequent public transportation,” said Marvin. “You’d need to have a certain amount of means in order to afford [Valley’s Edge], so I don’t see how it’s going to meet Chico’s housing needs. It would bring more people here, more congestion, more fire danger, and more traffic.”

“Honestly I think that what the city wants is for wealthy people from the Bay Area who can afford that housing to come here and pay more in taxes,” said Marvin. “They would really like that, and it would add to the bottom line of Chico, but I don’t think there’s many people in Chico who can afford it.” Brouhard said that the development will include hundreds of affordable units, but it isn’t yet clear what the entry-level price point for the development will be.

Brouhard told Grist that he supports center-city infill development as well, but he contends that Chico doesn’t have enough open space downtown to pursue the “grow up, not out” program that people like Marvin advocate. Decades ago, the city imposed a moratorium on all development in the expanse of farmland that borders it to the west, and many of the fire-prone hills to the east are on protected lands, which means there are few other directions where the city can expand. Much of Chico is zoned exclusively for single-family homes, and most buildings downtown are only a few stories tall. To build the number of housing units proposed for Valley’s Edge in the city center would require significant zoning changes that have long been controversial in California.

“You’d run out of infill very quick, even if you could develop it all — and the reality is, you can’t develop it all,” Brouhard said. “I don’t think it’s a serious plan to accommodate a community in a very sustainable manner. If you implemented that plan, what you would find is you can’t provide enough housing.”

The city has been failing to provide enough housing for some time: The homeowner vacancy rate in Chico was already hovering between 1 and 2 percent even before the Camp Fire, on par with New York City. A report later found that the city added only 15 low-income housing units between 2014 and 2019, and 2,000 for wealthier income tiers. Home sale prices and rental rates increased by as much as 20 percent in the first few months after the fire — and never came all the way back down. New development since then has been minimal.

Chico is not the only city where developers are trying to build in the WUI: A recent study from the U.S. Forest Service and the University of Wisconsin-Madison found that more than 6 million homes have been built in vulnerable areas nationwide over the past two decades, with much of the growth in eastern California. This pro-development mentality doesn’t seem to change in the aftermath of major fires, either: A U.S. Forest Service survey of California wildfires from 1970 through 2009 found that more than half of all buildings destroyed in wildfires were rebuilt within six years, and that there were “minimal trends toward lower risk areas” in where cities chose to place new buildings. The riskiness of new construction “either did not change significantly over time or increased.”

This casts doubt on the idea that traumatic events like the Camp Fire might jolt cities to diminish their zeal for WUI development. On the other hand, the California attorney general’s office released new guidelines last month that discourage local governments from approving developments on fire-prone slopes and other vulnerable places.

It remains to be seen whether Chico will follow the trend of pushing forward with housing development even after big fires. Brouhard presented the Chico city council with a final environmental impact report for the project last month, but it will be a new crop of city council members elected earlier this month who will determine the development’s fate: The attorney general’s new guidelines aren’t black-and-white, and it will be up to the council to determine whether Valley’s Edge meets them. In the district that contains the Valley’s Edge site, two candidates staked out opposite sides of the issue — one called it a “terrific project,” while the other “strongly opposes [it] as it is not what Chico needs.” The pro-Valley’s Edge candidate won.

If the council does approve the development, Marvin said that she and her fellow activists plan to sue under the California Environmental Quality Act, or CEQA, a 1970s-era law that is often used to challenge housing developments. CEQA is the reason why Brouhard’s environmental impact report for the project stretches to almost 700 pages, but the development’s opponents will likely try to poke holes in the review and allege that Brouhard hasn’t considered all the negative impacts of the development. Suing to stop development over concerns about fire risk has become more common in recent years: The California attorney general’s office has joined environmental organizations to file lawsuits against proposed developments in San Diego, Los Angeles, and Lake County, north of the Bay Area. All three challenges were successful.

Even if the CEQA lawsuit fails, Brouhard admits that it will take years to finish permitting for the development, which will also require him to secure approval from the Army Corps of Engineers to build on federal wetlands. It will be at least a decade beyond that before the whole project is completed.

It’s difficult to imagine now what Chico will look like in another 15 years, but fire danger is only going to keep rising. If Brouhard’s opponents are right, the developer’s pet project could someday become another Paradise. If the project isn’t built, however, the housing crisis in Chico may only get more painful.

“It’s very easy for a lot of people to say: Let’s just not build in these places,” said Mowery, the urban planner. “But is that really a long-term solution to all of the other realities that the West is going through with housing affordability? There are different ways that [risk] can be mitigated, and I think there is a lot of room to say: If it can be mitigated, then it can be built.”