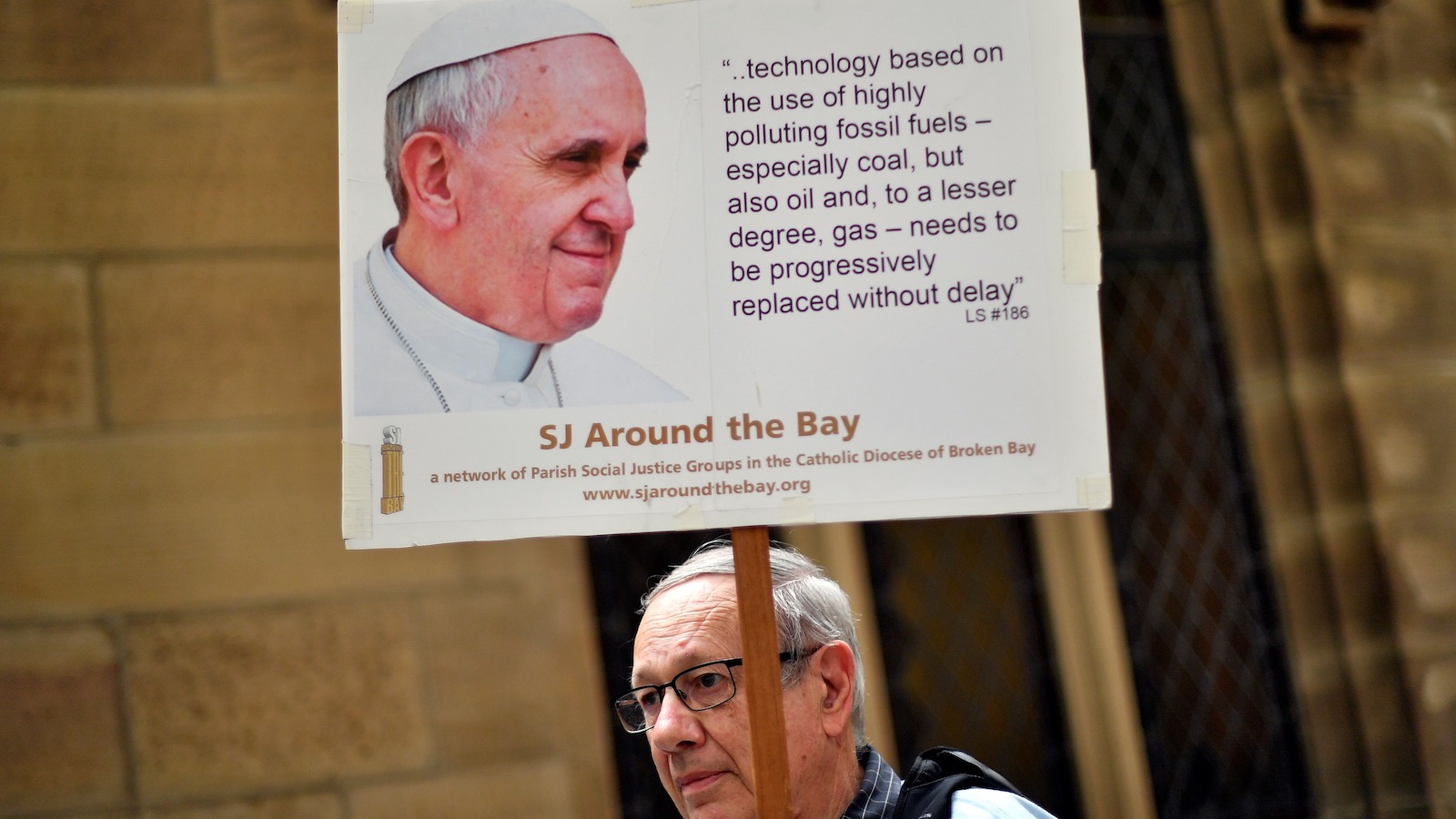

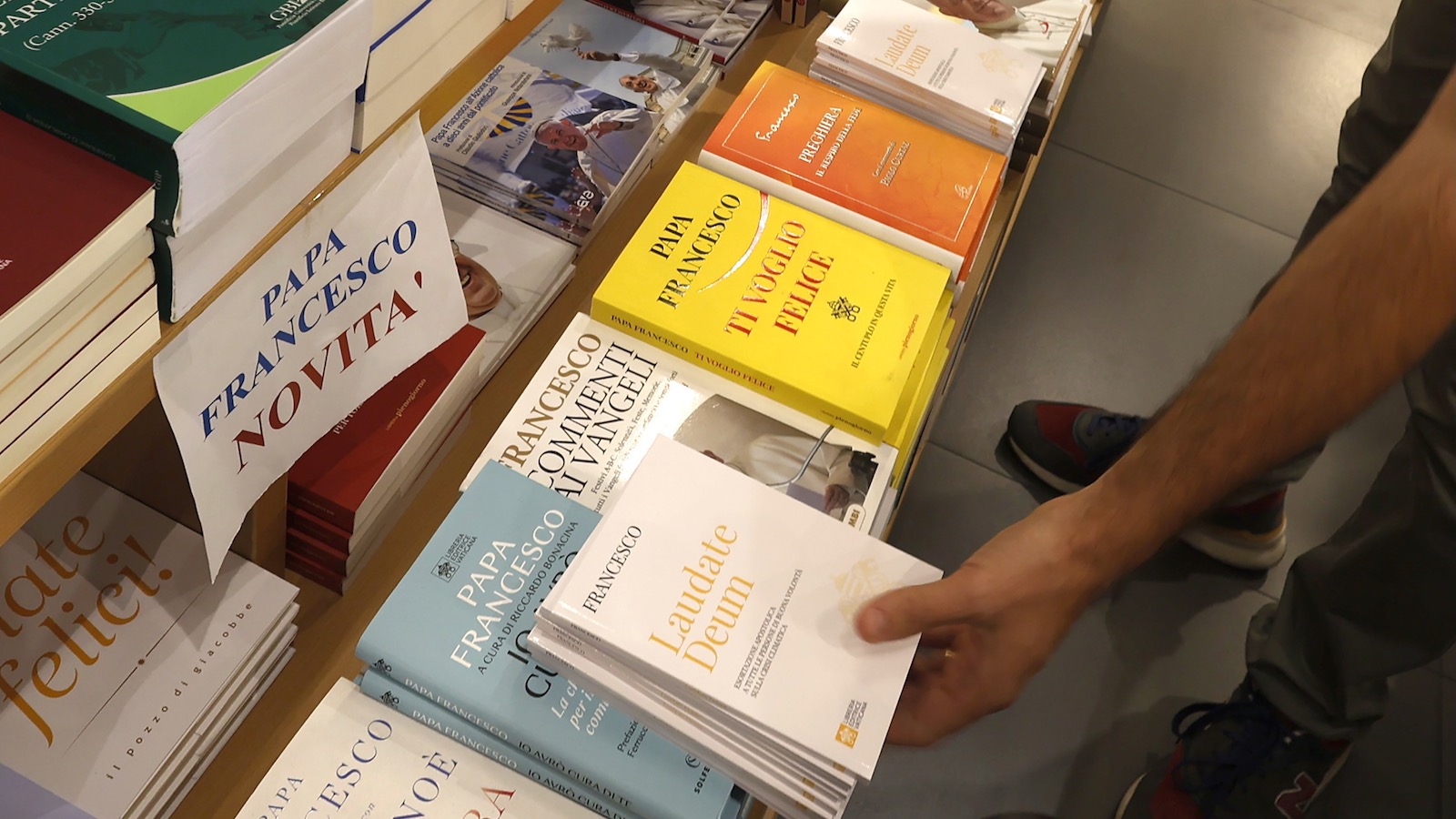

If there’s one person in the Catholic Church who ought to have the ability to influence climate action on a global scale, it’s the pope. And yet as Laudate Deum, his most recent exhortation on climate, demonstrates, even Pope Francis seems frustrated by how little has changed despite his best efforts.

The pontiff didn’t shy away from calling out those he sees as responsible, and after outlining the science proving that climate change is human-caused, he made clear that developing nations contribute little to the problem but bear the brunt of its impacts. He rejected the idea that technology alone will avert disaster and lamented the failure of repeated meetings of the Conference of the Parties to hasten the abandonment of fossil fuels. In drawing from scientific studies, governmental reports, and the works of authors like feminist tech scholar Donna J. Haraway, Francis showed a firm grasp of both the science and politics of climate change while conveying the moral and spiritual implications of the crisis, with the goal of urging “all people of good will” to act.

“Our responses have not been adequate while the world in which we live is collapsing and may be nearing the breaking point,” the Holy Father wrote in the document released October 4.

As the leader of a hierarchical institution with 1.36 billion adherents worldwide, the pope has authority over more people than all but two heads of state. From the first day of his papacy in 2013, Francis made clear that he would leverage his position for the sake of the planet. He took the name of the patron saint of ecology, and in 2015 released a landmark encyclical — the highest form of papal teaching on Catholic doctrine — on the environment, Laudato Si’, which some environmentalists have heralded as the most important climate document of the decade.

But reading Laudate Deum, it’s hard not to be struck by its tone of lament and exasperation at how little has changed in the eight years since Laudato Si’. “It feels like a sad document, as well as an angry one,” said Dorothy Fortenberry, a Catholic writer and intellectual. “There’s a real undercurrent of heartbreak.”

It’s not hard to see why. For all of Francis’ focus on the crisis — and the response from Catholics in much of the Global South — emissions have continued to rise. Support for his call to action has been lukewarm at best, however, in the country with the greatest per capita emissions. An analysis of official writings from U.S. bishops in the wake of Laudato Si’ concluded that the leaders of the Catholic church in America are “silent, denialist, and biased about climate change.” The response to Laudate Deum has been no better.

No wonder Francis is frustrated. The pontiff’s latest document, and the feelings expressed in it, offer a poignant reminder that no one person can fix things on their own. Laudate Deum hints at the importance of sharing and building collective power to effect change, and of working toward a better world no matter how bleak the outlook.

That Francis would express such strong views about the climate crisis is no surprise to those who have followed his papacy. He has represented, to many Catholics and non-Catholics alike, a refreshing direction for the Church. He has earned a reputation for being more open than his predecessors toward LGBTQ unions and the ordination of women. He remains an ardent critic of unbridled capitalism and consumerism. And he has emphasized consideration of the poor and established new processes for listening to and considering Indigenous perspectives.

That said, his positions don’t align neatly with those of any specific political party. In Laudato Si’, for example, Francis reaffirmed the Catholic Church’s official stance against abortion, which Fortenberry called “an attempt to remind everybody of his places of conservative overlap,” perhaps in a bid to convince that demographic to take seriously his calls for climate justice.

Making that call in an encyclical was no small thing. Such letters are the highest form of papal teaching and convey the Church’s point of view on a given topic. In Laudato Si’, Francis made clear that Catholics are called by God to be good stewards of “our common home.” The fact that he issued a follow-up focused on climate change is a sign that the crisis should be a top priority for the church, said Jose Aguto, executive director of the nonprofit Catholic Climate Covenant.

“It indicates how important this issue is for him,” Aguto said. “This is not a secondary aspect of the Catholic faith; it’s an integral aspect.”

The missive also reveals the Holy Father’s personal investment in the issue, Aguto noted. Where Laudato Si’ was likely shaped by “a lot of consultation and a lot of authors,” years of preparation, and appeals to Catholics across the political and theological spectrum, Laudate Deum has “a very personal tone to it,” Aguto said. “You feel Pope Francis’ direct voice in this.”

The pontiff’s deep personal connection to the issue is perhaps best exemplified by his being the first pope to take the name of Francis of Assisi, a saint known for his solidarity with the poor and his love of the natural world. Francis, who also is the first pope from Latin America, has channeled his namesake by seeming to intuitively understand that caring for marginalized people is impossible without caring for the land, water, and air they rely on. Throughout his papacy, he has repeatedly emphasized the connection between “the cry of the earth and the cry of the poor,” as he wrote in Laudato Si’.

For Catholics already working on climate, Francis’ latest exhortation may provide a reenergizing reminder that the Vatican is behind them, and that they are doing the right thing. “As a Catholic environmental family, we were completely thrilled at this,” said Christina Leaño, assistant director of the Laudato Si’ Movement. “It just gives us that extra motivation and excitement and hope.”

The very existence of Leaño’s organization is a testament to the impact the pope’s focus on climate has already had. Since the release of Laudato Si’, organizations focused on mobilizing Catholics to action have blossomed all over the globe, especially in Asia, South America, and Africa, where clergy and laity alike have been grappling with the crisis for years. Filipino bishops have, for example, called for Catholic institutions’ divestment from coal and transitioned their own parishes to solar. The archbishop of the Democratic Republic of Congo facilitated 12 days of “African climate dialogues” to highlight how the continent is impacted by climate change.

But Leaño recognizes that “there’s still quite a gap” between the Holy Father’s official statements and what is preached during weekly Mass here in the U.S. “If you talk to the average churchgoer, they will say that they have never or rarely heard about climate or environmental issues from the pulpit,” she said.

Sharon Lavigne is a devout Catholic whose work stopping a $1.25 billion plastics manufacturing plant from being built in her community earned her a 2021 Goldman Prize. Yet she hadn’t heard anything about Laudate Deum before Grist asked her about it. “I know in my church, we haven’t done anything [about the climate and pollution],” she said. “We haven’t even mentioned it.”

So why hasn’t one of the clearest priorities of the highest authority in the Catholic church been widely embraced here? One clue comes from the ways American Catholicism mirrors American politics.

One in four people in the United States identify as Catholic. A small but vocal number of them — a group that includes some bishops — has spent the last few years building a campaign that claims Francis is not the real pope, just as some within the Republican Party claim Joe Biden is not the real president. The point is to undermine Francis’ authority, said Fortenberry.

“The only way to square the circle that the guy at the top is making these extremely clear statements about church doctrine that are incompatible with certain aspects of right-wing ideology is to say that he’s not the pope,” she said.

If the pontiff seems frustrated, it’s no doubt because global emissions keep rising — but it’s likely also due to his encountering so many “dismissive and scarcely reasonable opinions,” as he wrote in Laudate Deum, from climate deniers within the church.

Though such views are exceptions, recent research shows that the nation’s Catholics are as a whole “no more likely than Americans overall to view climate change as a serious problem.” As with most people, it’s not denial that impedes action, but the demands of daily life. In Fortenberry’s experience, it’s not that people don’t believe in or care about climate change, it’s that they’re focused on other things.

For all the frustration laced through Laudate Deum, the document provides hints of what Francis hopes could invoke the kind of change he wants to see. It also reflects his belief that “every little bit helps, and avoiding an increase of a tenth of a degree in the global temperature would already suffice to alleviate some suffering.”

One change that could achieve that, he seems to think, is rethinking the kinds of hierarchies that give a handful of people so much power over others. “This feels like he’s in his ‘name names’ era,” Fortenberry said, noting the way that the pope criticized the COP process, called out this year’s host the United Arab Emirates as a “great exporter of fossil fuels,” and praised the activists “pressuring the sources of power.”

“In whose hands does all this power lie, or will it eventually end up? It is extremely risky for a small part of humanity to have it,” Francis wrote. “Unless citizens control political power — national, regional, and municipal — it will not be possible to control damage to the environment.”

Fortenberry and Leaño noted that Laudate Deum was released on the first day of the much anticipated Synod on Synodality, a conference to consider questions that could change the course of Catholicism. It has been called “one of the most important gatherings in the long history of the Catholic Church,” but at first glance, it seems unrelated to climate — the ongoing sessions bring together Catholic leadership and laity from around the world to discuss topics like the possibility of women’s ordination and the church’s relationship with the LGBTQ community.

But on another level, this synod is about the very thing the pope wrote about in Laudate Deum — the question of who is included, and therefore who has power. It hearkens back to the claims he made in his exhortation that “everything is connected” and “no one is saved alone.” If women feel the impacts of climate disaster more intensely, what impact might their ordination have on Catholic climate mobilization? If queer youth are more likely to be unhoused, and unhoused people are more vulnerable to extreme weather, what might a more queer-friendly church mean how that population experiences the climate crisis?

Ultimately, there’s no guarantee that the synod will succeed in making the church more inclusive, or that Laudate Deum will spark greater climate action from Catholics, let alone the rest of the world. But the very attempt to undertake them drives home one more takeaway from the Holy Father — that good work is worth doing, whether the outcome is promised or not.