It sounds like something out of a David Foster Wallace novel.

In his extremely heavy 1996 book Infinite Jest, Wallace writes about a dystopian future where everything is sponsored, even years: Instead of 2005, you have the Year of the Perdue Wonderchicken. Instead of 2009, you have the Year of the Depend Adult Undergarment. Ludicrous, right?

Or is it?

While we have yet to sell years to the highest bidder, another important resource may soon be up for grabs: national parks.

An $11 billion maintenance backlog has National Park Service Director Jonathan Jarvis proposing “an unprecedented level of corporate donations” to the national parks, as The Washington Post describes it. In return for their money, companies would get an unprecedented amount of exposure in those parks.

So does this mean that you could soon visit Yellow Cab’s Yellowstone? Marlboro’s Great Smoky Mountains? Crest Whitestrips’ White Sands?

No. Under the current proposal, corporate logos and naming rights would be limited to park facilities like visitor centers and to things like educational and youth programs.

Critics, however, are not pleased.

“You could use Old Faithful to pitch Viagra,” Jeff Ruch, executive director of Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, a group opposed to the change, told the Post. “Or the Lincoln Memorial to plug hemorrhoid cream. Or Victoria’s Secret to plug the Statue of Liberty. … Every developed area in a park could become a venue for product placement.”

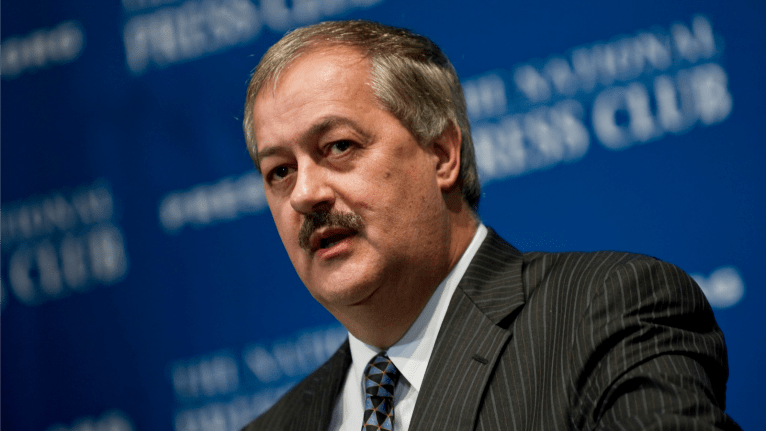

Corporate and private support of national treasures is part of an increasing trend: The New Yorker wrote earlier this year about David Rubenstein, cofounder of the private-equity firm Carlyle Group, who used a small portion of his $2.6 billion fortune to fix the Washington Monument after it was damaged in an earthquake in 2011. “It’s great that he’s helping out with the Washington Monument,” tax-law professor Victor Fleischer told The New Yorker’s Alec McGillis. “But, if we had a government that was better funded, it could probably fix its own monuments.” The same could be said of its parks.

David Foster Wallace might not approve of this development, but were he still alive, he wouldn’t be surprised.