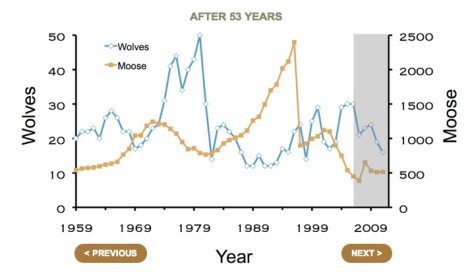

On Isle Royale, way up north in Michigan, scientists have been tracking how populations of moose and wolves grow and shrink in response to each other and outside influences. It’s a lovely natural experiment that scientists have been following for decades, making this “the longest continuous study of any predator-prey system in the world,” researchers say. But it may soon be coming to an end — not because the science is done, but because the wolves are. The Isle Royale pack has no puppies this season, and without intervention, little hope of lasting much longer.

The researchers wrote recently about how this moose-wolf relationship began:

Moose first appeared on this Michigan island in the first decade of the 20th century, apparently by swimming from the mainland. With no predator to challenge them, the moose population surged (interspersed by two crashes, from starvation) and devastated the island’s vegetation in search of food. Then wolves arrived in the late 1940s by crossing an ice bridge from Canada, and began to bring balance to an ecosystem that had lurched out of control.

But it’s not often that an ice bridge forms or that new wolves cross over. And over time, the population of wolves has shrunk, so much so that now there’s only one signature Y chromosome in all the island’s wolves. Wolves avoid inbreeding. (They are smart enough to realize that, ew, that’s your sister, man!) But now the population is so small — there are only eight of them left — that they don’t have other mating options. So, no mating. No wolf puppies. And soon, no wolves.

The situation has left conservation biologists to ponder whether or not they should intervene. One side believes in letting nature runs its course — even if it means letting the wolves go extinct — and then bringing fresh wolves to the island to control the bountiful moose population. The other side believes that intervention is necessary, and wild wolves and new genetic material should be imported to rescue the population, as was done with the Florida panther.

Meanwhile, the moose aren’t doing so great, either. Their numbers are pretty low — even with only eight aging wolves to pester them, they still have to deal with problems like ticks. Why can’t it be the ticks that are going extinct?