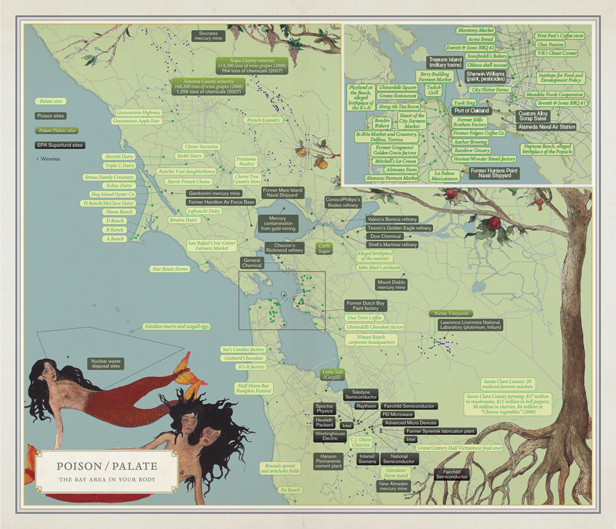

Editor’s note: The following essay and map are excerpted from Infinite City: A San Francisco Atlas and are republished with permission by UC Press as part of Grist’s California agriculture series, an exploration of the people, farms, and issues shaping the state.

The Bay Area is a tale of two valleys, places that call up very different associations. Napa Valley is the opposite of Silicon Valley, or likes to think so. Napa Valley is how the region is marketed, as upscale, arcadian, sensual, and leisurely; Silicon Valley is its other face, hectic, disembodied, corporate, and geeky, though the sweatshop tech work is now done mostly overseas. Of course, the meaning of each place, and their relationship to each other, is more complicated. Napa is a second-home capital for the wealthy, including those who’ve made a killing in technology. You make software to engineer the future and buy pseudo-Tuscan nostalgia with the profits.

Visually, the valley in the north is a pastoral vision of green gridded vineyards and rustic architecture — the gigantic wooden fermenting barrels were one of the wondrous sights of my childhood. Making wine is as traditional as making electronics communication technology, new devices, and software is not. And certainly the suburban expanse of Silicon Valley is dystopian: a landscape of workspaces, shopping, and sprawl scattered any which way and connected by a network of highways prone to gridlock. But if you include the farmworkers whose lives in the wine country are not so gracious, you can begin to locate the affinities between the two places.

Not so long ago, the southern region was the Valley of Heart’s Delight, one of the great orchard landscapes of the world, with plums, apricots, and cherries the major crops. The sight and smell of the orchards in bloom were said to be spectacular, though picking apricots, plums, and cherries was not so arcadian a pursuit. Workers’ conditions there were part of what inspired Cesar Chavez to take up the struggle for farmworkers’ rights (at the outset of his political career, he lived in a San Jose barrio nicknamed Sal Se Puede [Get Out If You Can]). That was when San Francisco was the industrial capital of an agrarian region, when the city had branch railroads feeding ingredients to the big breweries, canneries, food factories, and coffee processors near the waterfront, and when Mission Bay was a railyard, not a biotech campus. Some of this still remains: a significant proportion of the coffee drunk in the United States continues to come through the Golden Gate, though it now comes through the Port of Oakland, not San Francisco.

In many industries, food and poisons are intertwined: C&H Sugar, near the Carquinez Bridge, is both a major sugar refinery and a toxic polluter. Just south of this map, in Watsonville, the strawberry capital of the nation, a major battle has been waged over use of the deadly, ozone-depleting fumigant methyl bromide. And in the Napa Valley vineyards and wineries, vast quantities of chemicals are used in the raising of wine grapes and some more in the production of most wine, although this doesn’t compare to the legacy of Silicon Valley, which is home to the greatest concentration of Superfund toxic cleanup sites in the nation — 29, in various states of toxicity.

The Bay Area is now legendary, and sometimes smugly so, as a culinary capital, home of Chez Panisse and Greens and various other upscale dining emporia, fancy markets, and more. Since the Gold Rush, locals have liked to eat well, though the first famous dish to emerge from the place was hardly genteel in name or taste: the Hangtown Fry — eggs scrambled with oysters and bacon. There were elegant restaurants like the Old Poodle Dog, open from 1849 to 1922, and Jack’s, the French restaurant that closed in 2009 after operating since 1864. The city blithely ignored Prohibition, though the wine grown in Napa and home-brewed by the huge Italian population wasn’t always so refined. The Bay Area was once a much more rough-and-ready place, and the food it produced was on a grander scale but a less epicurean level before everything changed.

A lot of the local food of yore was funny. The Popsicle is said to have been invented in the 1920s at Neptune Beach, a little Alameda amusement park, since contaminated by the Navy; the martini in refinery capital Martinez; the It’s-It ice cream sandwich at the long-gone Playland at the Beach amusement park; and the mai tai at Trader Vic’s in Oakland, also gone. Rice-A-Roni, a name hard to say without appending “the San Francisco treat,” resulted from the packaging of an Armenian rice-pasta dish by an Italian family whose Gra-gnano Products bulk pasta factory in the Mission District — around the corner from today’s gourmet mini-ghetto of Delfina, Bi-Rite Market and Creamery, and Tartine — eventually became Golden Grain in the 1930s and migrated to Fremont in the 1950s (near where the Ghirardelli Chocolate factory, once in northern San Francisco, also ended up). Rice-A-Roni was invented in the late 1950s, in the golden age of dried parsley flakes, cake mixes, and recipes whose first ingredient was a can of Campbell’s Soup. The bricks of hot-pink popcorn sold in Golden Gate Park and at the zoo were another local treat that hardly merits the term “delicacy,” though they are my madeleines. (They’re still made at the Wright Popcorn and Nut Company in the Mission.)

The region was both a prolific producer of food — of fish, of wine, of produce, if not of grains — and home to a vast array of cuisines. Chinese food has been cooked here since the first Chinese immigrants arrived, and Mexican food long before. And San Francisco can claim to be one of the coffee capitals of the nation — Italian North Beach was full of espresso machines steaming and Graffeo coffee roasting back in the era when I thought the Central Valley should have a sign for those heading east saying, “Next Good Coffee 3,000 Miles.”

Food evolved. Some of the Hangtown Fries must have been made not with chicken eggs but with murre and seagull eggs harvested from the Farallones, those rocky little islands 10 miles off the coast — Petaluma had yet to become the Egg Basket of the World, as it did in the teens of the last century, producing more than half a billion eggs per year by 1917. The Egg War on the Farallon Islands was fought to control the commodity in 1863, and two lives were lost. The Farallones are now a bird sanctuary, and Petaluma’s chickens are mostly gone, though Clover Stornetta processes milk and dairy products on a large scale at a creamery in the vicinity, and the Petaluma area has seen a small free-range chicken farming revival (in addition to the chickens that can be found in countless urban backyards nowadays). Food is part of the Bay Area you hear about nowadays, exquisite upscale food at famous restaurants and gourmet markets. But it’s so boring we couldn’t stay focused on it in this map.

More important is the populist and radical foodscape — certainly the burrito has flourished in San Francisco as nowhere else, and these biomass logs sustain many a student and day laborer in the Mission. As does a politics of radical food, from Frances Moore Lappé’s 1971 Diet for a Small Planet, the first manifesto with recipes (for bean-based protein dishes, mostly), to the Futurefarmers’ 2008 Victory Gardens and the inner-city farms in San Francisco and West Oakland. The Black Panthers served breakfast to inner-city children, and the Symbionese Liberation Army forced Examiner newspaper mogul Randolph Hearst, father of the kidnapped Patty Hearst, to give away groceries on a grand scale. This place is rife with food as redemption, from Cathy Sneed’s food-gardening project at the San Francisco County Jail, begun a few decades ago; to Mission Pie, which connects inner-city youth to jobs in food production at Pie Ranch, a peninsula farm, and in food preparation at a diner in the Mission; to La Cocina, a flexible industrial kitchen that helps poor women set up small food enterprises.

Another landscape of labor poisoned workers and left behind more toxins for the rest of us. The New Almaden mine at the southern end of the region supplied a lot of the mercury used to refine gold during the Gold Rush; the miners ended up putting 10 times as much mercury into the water systems of California as the amount of gold they took out of streams and rivers and rock and dirt. The region is still dotted with ancient mercury mines, many of them continuing to leach toxins. The Silicon Valley Toxics Coalition long ago pointed out that the high-tech industry is not nearly as clean as its image.

Bay water, groundwater, soil, food — and then there’s the air. Chevron is not only involved in human rights abuses and environmental devastation in other countries; it’s also the biggest emitter of greenhouse gases in California and is responsible for more readily detectible emissions such as ammonia and benzene, which affect the 17,000 poor people who live within three miles of Chevron’s Richmond refinery. In 1999, the refinery suddenly released 18,000 pounds of sulfur dioxide and told 10,000 residents to stay inside; those who lived even closer were evacuated. The stuff “killed trees and took the fur off squirrels,” a resident reported. The Bay Area is one of the centers of the environmental justice movement in part because it’s also a center of environmental injustice, in Richmond and all through the toxic corridors of refineries and chemical plants along the Carquinez Straits, in San Francisco’s Hunters Point, in Silicon Valley, and among farmworkers.

The Bay Area is good at containing contradictions: being both the great laboratory for new military technologies and the capital of opposition to militarism, being both Tuscany and the starship Enterprise, making both delights for the palate and poison for the body. Behind the latter conundrum lies its constant tension between being more sensual and engaged with place, substance, and pleasure, on the one hand, and more sped-up, technological, profitable, and disembodied, on the other. Such contradictions may never be resolved, but they can at least be recognized. Even tasted.

Copyright © 2010 by the Regents of the University of California.