The vision

“We need to reimagine what critical infrastructure means. If one person would die because of a lack of power, that house is critical energy infrastructure, and it needs to be equipped with alternatives to save that one life.”

Marcel Castro, professor of electrical engineering at the University of Puerto Rico, Mayagüez

The spotlight

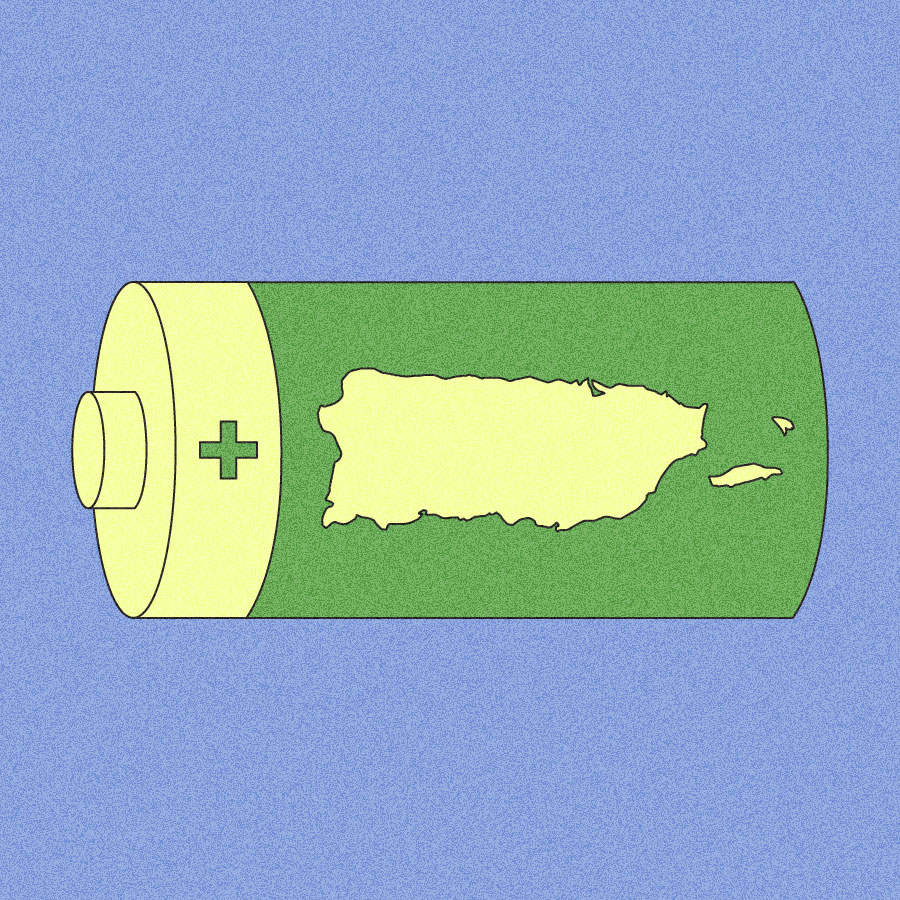

In Puerto Rico, power outages are a part of daily life. After the devastation of Hurricane Maria in 2017, 200,000 homes went without power for more than five months, and around 62,000 went as long as 11 months. Even before the storm, the U.S. territory’s energy system was outdated and failing — and nearly five years later, many still struggle with regular outages.

Grist’s climate solutions writer, Gabriela Aoun Angueira, has paid attention to the archipelago and its energy story for a long time. Her mother is from Puerto Rico, and her family still lives there. And earlier this year, she noticed that U.S. Secretary of Energy Jennifer Granholm had visited Puerto Rico three times since the fall — another trip planned for March would be her fourth in nearly as many months.

“That’s not really a level of attention that I think Puerto Rico is used to from the federal government,” Aoun Angueira says. She wondered if this was a sign of positive change — and she asked the Department of Energy if she could tag along for the March visit.

“[Granholm] was going down there on essentially a listening tour,” Aoun Angueira says, to learn from locals how they wanted the government to spend a $1 billion resilience fund that Congress allocated in December. On the tour, Granholm and her team visited some of the most remote communities in the mountains of Puerto Rico, conducting town halls and visiting people in their homes to hear about their experiences with energy reliability. What they heard repeatedly was that people lack trust in the institutions that have failed them. And, facing outages on a weekly or even daily basis, Puerto Ricans are enacting their own energy solutions.

“What they were looking for was a way to decentralize their energy system, so that they didn’t have to rely on a centralized grid that wasn’t serving them and a utility that wasn’t serving them and a government that really wasn’t serving them,” Aoun Angueira says.

She wrote about the visit for Grist, and says she was inspired by the community-led solutions she witnessed. While they are homegrown from necessity in Puerto Rico, they also offer lessons in creativity and adaptability that could be applicable beyond the territory.

Subsistence solar

Rooftop solar, combined with battery storage, has emerged as one way to ensure household energy security. Since Hurricane Maria, the installation of photovoltaic systems has increased tenfold across the archipelago, Aoun Angueira reports. But this solution is cost prohibitive for many residents — the median household income in Puerto Rico is just shy of $22,000, while a full solar-and-battery system can cost upward of $30,000.

Marcel Castro, a professor who studied power outages after Maria, is proposing a different option for solar — one that could help limited funding go further. Photovoltaic systems with enough energy to power just essential services could cost as little as $7,000, he says. That would enable residents to keep things like fridges and medical devices running while they wait for the power to come back on.

Community microgrids

For remote towns in the mountain ranges on Puerto Rico’s main island, dense vegetation conflicts with power lines, and steep, narrow roads can make it difficult to repair energy infrastructure after storms. One resident who took part in a town hall in March told the energy secretary that, “When the power goes out, it can be a week to get it back.”

One such town, Castañer, has invested in a microgrid solution. The town’s two microgrids power two homes and seven businesses, including essentials like a grocery store. The backup batteries can keep the businesses online for up to 10 hours after a power outage. And, importantly, the microgrid contract stipulates that businesses will let residents come to plug in their phones and refrigerate medicines when the power goes out. After Hurricane Fiona last fall, Aoun Angueira reports, one woman powered her lung therapy machine at the local ice cream shop.

The cooperative that runs the microgrids wants to build six to eight more in neighboring towns within the next 18 months.

However, Aoun Angueira points out, a model like this won’t help residents who are unable to leave their homes — more widespread household-level solutions are still needed for the most vulnerable community members, and to help ease the burden of high energy bills.

Solar as a service

In the coastal town of Isabela, one local nonprofit, Barrio Eléctrico, is aiming to lower the barriers to household solar and battery systems by offering them as a service. Rather than paying to install a system of their own, residents can pay relatively small upfront costs (a $25 initiation fee plus a $120 deposit) to install hardware owned by the nonprofit. They then benefit from reduced monthly electricity bills and don’t bear responsibility for potentially costly repairs.

The organization is able to offer low rates by attracting U.S. investors who can take advantage of federal solar tax credits that are currently unavailable to Puerto Ricans, Aoun Angueira reports. As of last month, Barrio Eléctrico had installed 36 systems. The org hopes to scale that up to 1,500 by the middle of next year.

Empowering communities to lead

The $1 billion fund may sound like a big investment in energy resilience, but how many people it will actually help depends on how exactly it gets spent. “There’s so much talk about how these government programs don’t get input from the community before they’re designed,” Aoun Angueira says, adding that this is why the secretary’s listening tour was so important. “This looked to me like it could be an actual model of how to go about a program like this, and how to improve upon the mistakes that have been made in the past.”

The Department of Energy wants to start disbursing the funds by the end of this year to provide energy security as quickly as possible where it’s needed most. Overhauling Puerto Rico’s grid will take many more years — but some residents are also energized about that future. One of Aoun Angueira’s favorite parts of the trip was visiting the university in Mayagüez, where electrical engineering students were eager to present their visions and ideas to the secretary.

“They had so much hope for Puerto Rico,” she says. “They really wanted Puerto Rico to be more than just a place that got help, but a global center for finding solutions to these issues.”

More exposure

- Read: more about a microgrid installed earlier this year in Adjuntas, Puerto Rico, and about the rooftop solar and battery boom (Grist)

- Read: more about the resilience fund and long-term energy goals for Puerto Rico (Canary Media)

- Read: about complaints against LUMA Energy, the Canadian-American company that took over management of Puerto Rico’s grid in 2021 (The Hill)

- Watch: Bad Bunny’s 23-minute music video for “El Apagón,” which includes the short documentary Aquí Vive Gente, exploring Puerto Rico’s energy challenges and the past and present of colonialism and inequality

See for yourself

As always, we welcome your feedback, questions, or any personal anecdotes you’d like to share. Just hit reply to this email to let us know what’s on your mind. (Or send in a drabble about how you visualize the future of decentralized, resilient energy systems!) We would especially love to hear from any readers in the Caribbean.

On our horizon

Grist is partnering with the Center for Rural Strategies to offer $100,000 in reporting grants for stories about and for rural communities across the United States. Learn more here — and please share!

A parting shot

Another facet of Puerto Rico’s clean energy journey that Aoun Angueira covered in her piece is the need for workforce development. It’s not enough to direct funding toward solar panels and other hardware — a local workforce will be needed to install, inspect, repair, and maintain them. That would require investing in the archipelago’s struggling education system, which has suffered from federally imposed austerity measures. “It’s a reminder of how colonialism can undermine the green transition, but it’s also an example of how there are opportunities to address many challenges at once,” says Aoun Angueira. In this photo, a worker from Barrio Eléctrico installs a battery and an inverter at a home in Isabela, Puerto Rico.