This story was originally published by CityLab and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Paris has inaugurated its first bike highway. Opening last May, the 0.5-mile stretch of freshly paved road alongside the Bassin de l’Arsenal is part of the Réseau express vélo (“REVe”), an initiative to build fast-track bike lanes free of motorized vehicles. It’s only the first section of the soon-to-be 28-mile network of bike highways that will cross the city by 2020.

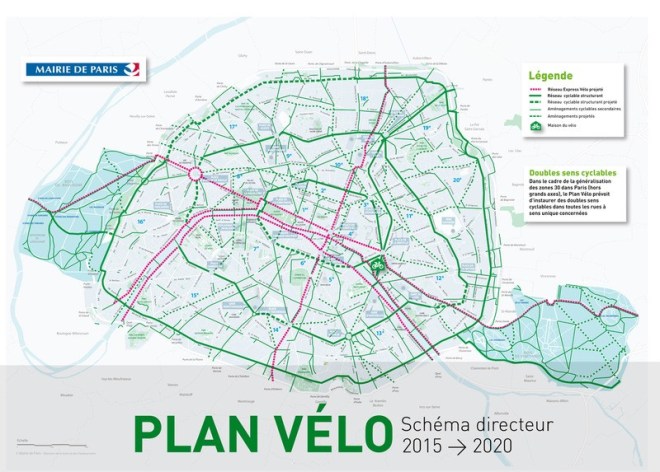

In 2015, the city voted unanimously to spend €150 million ($164.5 million) on expanding and improving its biking infrastructure, including REVe (which translates to “dream” in French). Cyclists will benefit from more bike-friendly rules — including the freedom to turn without waiting for a green light at every intersection — as well as new bike stands and two-way bike lanes on one-way streets.

Sandrine Gbaguidi, a local biking blogger, rarely leaves home without her bike, using it to run errands, get to work, or just find a nearby park. But that wasn’t always the case. When Gbaguidi moved to Paris from Dakar six years ago, she first used public transit to get around because she was too afraid to bike. She bought a bike after three years in Paris — and, as she feared, there was a steep learning curve. “You’re constantly on your guard and annoyed or irritated,” says Gbaguidi. “Biking is supposed to be fun and relaxing.”

The plan for the new REVe network.Mayor of Paris

Gbaguidi’s initial fears are not unique. In 2014, bikes amounted for only 5 percent of daily traffic in the city, accounting for about 225,000 trips. Although that number is growing annually, it still doesn’t compare to the 15.5 million daily trips by car, tallied in 2012. Meanwhile, other European cities like Copenhagen and Amsterdam report 55 and 43 percent, respectively, of their daily traffic happening on bikes.

Charles Maguin, president and co-founder of Paris en Selle, a biking association, says one reason people don’t bike in France’s capital is that they don’t feel safe competing with motorized vehicles on the road. Paris en Selle was founded in 2015 when Maguin noted the lack of biking groups advocating for the cyclist’s safety in terms of laws and infrastructure. “Parisians would rather take the Metro for a short commute than bike to work,” says Maguin.

But the Metro, while popular, is not valued for comfort or cleanliness, especially during rush hour. Commuters breathe in more pollution using the Metro than while riding a bike, according to a study conducted in 2009 by Airparif, an association monitoring atmospheric pollution in the greater Paris area.

Above ground, Maguin says that since the automobile became popular in the 20th century, the city has continued to prioritize cars over bicycles and pedestrians. To this day, there‘s a persisting stereotype of an average cyclist as a Parisian “bobo,” or hipster, biking in the city with a baguette in their front basket. But Maguin stresses that this cliché is outdated as more people consider biking for getting around the city. All that’s missing is the right infrastructure to encourage more riders.

By 2020, Paris will double its bike lanes, from 435 to 870 miles.

Hélène Bauer

Riding a bike in Paris is as much a mental workout as it is a physical one. Although there are bike lanes on most roads in the city today, cyclists are still being pushed out by other vehicles that share the same lane. Sharing the road with motorized vehicles creates a sense of insecurity, says Maguin.

The new REVe network aims to counter that. With these new bike lanes, the city hopes to see daily bike trips increase from 5 to 15 percent by 2020. The initiative will not only build highways for bikes, but it will also double the number of bike lanes from 435 to 870 miles, making the system more efficient and inclusive. And with the creation of 7,000 more advanced stop lines at red lights (with priority given to bikes at every intersection), cyclists won’t be as restricted by car traffic.

Paris mayor Anne Hidalgo’s initiative to create a more bike and pedestrian-friendly city is part of a multi-year plan to make the city greener, including goals to reduce car traffic on its roads and the air pollution it creates. One of Hidalgo’s projects even involves turning major boulevards like the Champs Élysées into pedestrian streets.

Paris en Selle salutes the mayor’s effort to incorporate cyclists into city planning, but wants to push these initiatives even further. “I hope that biking gets to be considered as a viable alternative means to get around the city, and not just a project run by green parties for the Parisian hipster,” says Maguin.