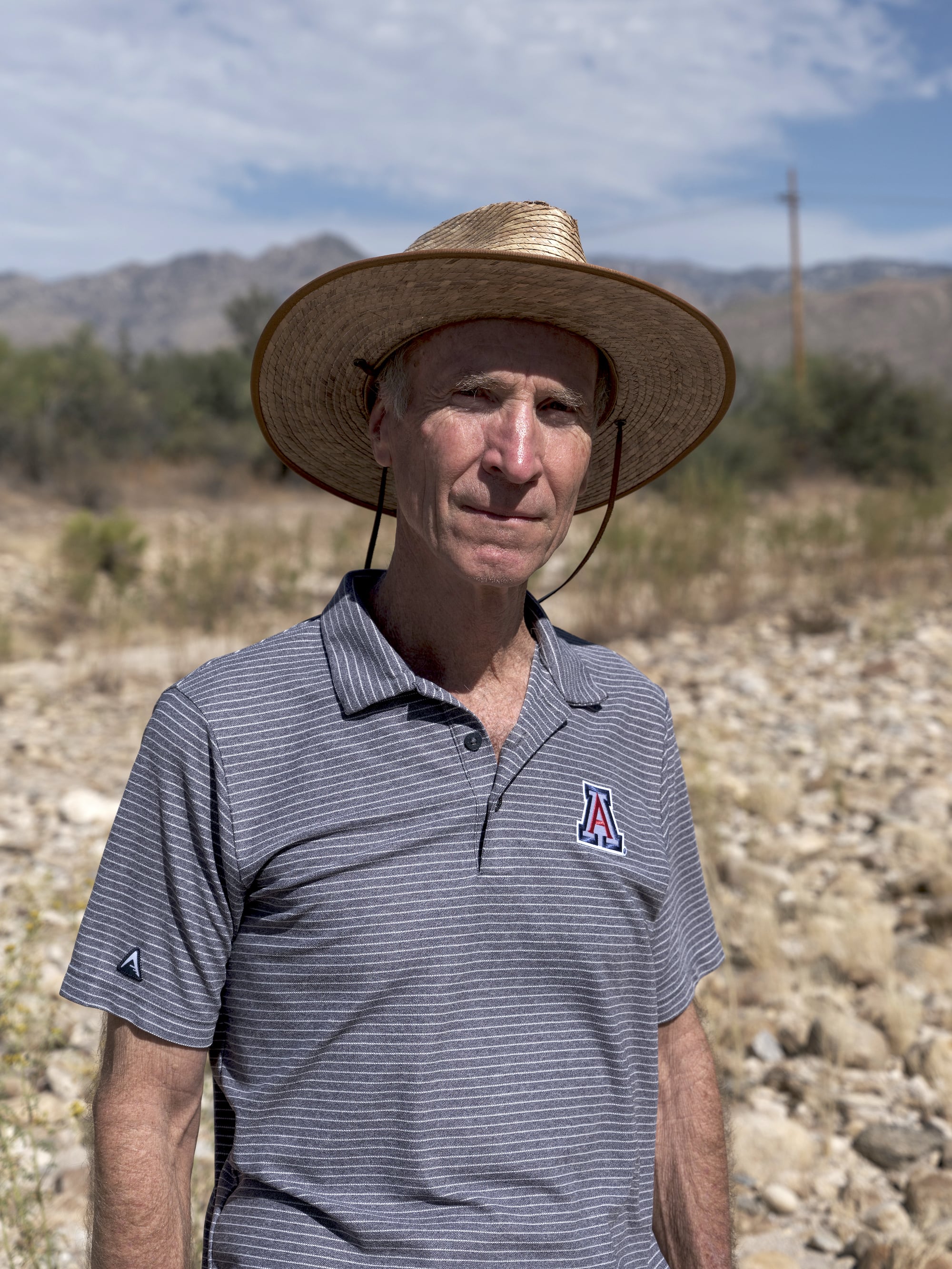

The morning temperature is nearing 100 degrees Fahrenheit as Keith Seaman sweats beneath his bucket hat, walking door to door through the cookie-cutter blocks of a subdivision in Casa Grande, Arizona. Seaman, a Democrat who represents this Republican-leaning area in the state’s House of Representatives, is trying to retain a seat he won by a margin of around 600 votes just two years ago. He wants to know what issues matter most to his constituents, but most of them don’t answer the door, or they say they’re too busy to talk. Those that do answer tend to mention standard campaign issues like rising prices and education — which Seaman, a former public school teacher, is only too happy to discuss.

“We’ll do our best to get more public money into education,” he tells one man in the neighborhood, before turning to the constituent’s kindergarten-age daughter to pat her on the head. “What grade are you in?”

“Why are you at our house?” the girl asks in return.

Seaman has knocked on thousands of doors as he seeks reelection this year. While his voters are fired up about everything from inflation to abortion, one issue doesn’t come up much on Seaman’s scorching tour through suburbia — even though it’s plainly visible in the parched cotton and alfalfa fields that surround the subdivision where he’s stumping for votes.

That issue is water. In Pinal County, which Seaman represents, water shortages mean that farmers no longer have access to the Colorado River, formerly the lifeblood of their cotton and alfalfa empires. The booming population of the area’s subdivisions face a water reckoning as well: The state has placed a moratorium on new housing development in parts of the county, as part of an effort to protect dwindling groundwater resources.

Over the past four years, Arizona has become a poster child for water scarcity in the United States. Between decades of unsustainable groundwater pumping and a once-in-a-millenium drought, fueled by climate change, water sources in every region of the state are under threat. As groundwater aquifers dry up near some of the most populous areas, officials have blocked thousands of new homes from being built in and around the booming Phoenix metropolitan area. In more remote parts of the state, water-guzzling dairy farms have caused local residents’ wells to run dry. The drought on the Colorado River, long a lifeline for both agriculture and suburbia across the U.S. West, has forced further water cuts to both farms and neighborhoods in the heart of the state.

Arizona voters know that they’re deciding the country’s future — the state is one of just a half-dozen likely to determine the next president — but it’s unclear if they know that they’re voting on an existential threat in their own backyards. The outcome of state legislative races in swing districts like Seaman’s will determine who controls the divided state legislature, where Democrats are promoting new water restrictions and Republicans are fighting to protect thirsty industries like real estate and agriculture, regardless of what that means for future water availability.

“Everybody’s running for reelection,” said Kathleen Ferris, who crafted some of the state’s landmark water legislation and now teaches water policy at Arizona State University. “Nobody wants to sit around the table and try to deal with these issues.”

For these lawmakers’ voters, topics like abortion, the economy, and public safety are drawing far more attention than the water in their taps, and it will be these issues that drive the most people to the polls. But for the state officials who win on election day, their most consequential legacy may well be what they decide to do about the future of water in Arizona.

“They keep saying, ‘Well, water is nonpartisan,’” Ferris added. “That’s not true anymore. It’s really not true.”

It’s not hard to see why hot-button issues like immigration and the cost of living are on the minds of Arizona voters: The state sits on the U.S.-Mexico border and has experienced some of the highest rates of inflation in the country over the past few years. Meanwhile, its Republican-controlled state legislature has cut public education funding and allowed a 19th-century abortion ban to remain in effect after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade. The state is at the center of almost every major political debate — “the center of the political universe,” in Politico’s words — and its nearly evenly divided electorate makes its swing votes key to determining who controls both the White House and Congress.

Even when the temperature doesn’t top 115 degrees F, the resulting campaign frenzy can make an out-of-state visitor lightheaded. Lawn signs clutter gas station parking lots, highway medians, and front yards; virtually every other television commercial is an ad for or against a candidate for Congress, the presidency, or some state office. A commercial slamming a Democratic candidate as a defund-the-police radical will frequently air right after an ad condemning a Republican as a threat to democracy itself. Mailers and campaign literature clog mailboxes and dangle on doorknobs.

This avalanche of campaign advertising seldom mentions water. During a week reporting in the state, I saw exactly one ad that focused on the issue. It was a billboard in Tucson announcing that Kirsten Engel, the Democratic candidate for a pivotal congressional seat, supports “Protecting Arizona from Drought” — not exactly the most substantive engagement with the issue.

The reason for this avoidance is simple, according to Nick Ponder, a vice president of government affairs at HighGround, a leading Arizona political strategy firm. He said that while many voters in the state rank water among their top three or four issues, most don’t have a detailed understanding of water policy — meaning it’s unlikely that they’ll vote based on how candidates say they’ll handle water issues.

“They understand that we’re in a desert, and that we have water challenges — in particular groundwater and the Colorado River — but I don’t think that they understand how to best manage that,” he told Grist.

And how could they? Understanding Arizona water policy involves a maze of acronyms — AMA, GMA, INA, ADWR, CAWS, DAWS, DCP, CAP, and CAGRD are just the entry-level nouns — and complex technical models that track water levels thousands of feet underground. Even many elected officials on both sides of the aisle aren’t well versed in the issue, so they defer to the party leaders who have the strongest grasp on how the state’s water system works.

One upshot of this confusion — as well as the state’s bitter partisan divide — is that, even as Arizona’s water crisis has gained national attention, state lawmakers have failed to pass significant legislation to address the deficit of this critical resource. Over the past two years, the state’s Democratic governor, Katie Hobbs, has been unable to broker a deal with the Republicans who control both chambers of the state legislature. Hobbs has put forward a series of proposals that would reform both agricultural water use in rural areas and rapid development in the suburbs of Phoenix, but she has come up a handful of votes short of passing them. Republicans have put forward their own plans — which are friendlier to the avowed water needs of farmers and housing developers — that she has vetoed.

Once you cut through the thicket of reports and acronyms, it’s clear that this year’s election is pivotal for breaking this gridlock and determining the future of water policy in the state. Republicans hold one-vote majorities in both chambers of the legislature, so state Democrats only need to flip one seat in each chamber in order to gain unified control of the government. If that happens, Hobbs will be able to ignore the objections of the agriculture and homebuilding industries, which have kept Republicans from signing on to her plans.

Hobbs and the Democrats want to limit or prohibit new farmland in rural areas, while simultaneously making it harder for homebuilders around Phoenix and Casa Grande to resume building new subdivisions. This would slow down, but not reverse, the decline in water levels around the state — and it would likely diminish profits for two industries that are pillars of the state’s economy. If Republicans retain control of the legislature, they would reopen new suburban development and roll out more flexible rules for rural groundwater, giving a freer hand to both industries but incurring the risk of more groundwater shortages in decades to come.

Legislators came close to reaching agreement on both issues earlier this year. Republicans passed a bill that would relax development restrictions on fallow farmland where housing tracts could be developed — a compromise with theoretical appeal to both parties’ desire to keep building housing for the state’s booming population — but Hobbs vetoed it, saying it lacked enough safeguards to prevent future water shortages. At the same time, lawmakers from both parties made progress on a deal that would allow the state to set limits on groundwater drainage in rural areas, but the talks stalled as this year’s legislative session came to a close.

“We had so many meetings, and we’ve never gotten closer,” said Priya Sundareshan, a Democratic state senator who is the party’s foremost expert on water issues in the legislature. “Now we’re in campaign mode.”

In Seaman’s district of Pinal County, where water restrictions have created difficulties for both the agriculture and real estate industries, many of those who are engaged on water issues see a stark partisan divide. Paul Keeling, a fifth-generation farmer in Casa Grande, framed the shortage of water on the Colorado River as a competition between red Arizona and blue California.

“We’re supposed to be able to get a part of that water, and now we can’t,” he told Grist. “It’s all going to California, to the f***ing liberals and the Democrats.”

Keeling has had to shrink his family’s cotton-farming enterprise over the past few years, because he’s lost the right to draw water from the canal that delivers Colorado River water to Arizona. It’s one reason among many that Keeling said he’s supporting former President Donald Trump this year, as he has in the past two elections.

The Republican leadership of Pinal County has sparred with Governor Hobbs and state Democrats on housing issues as well, albeit in far less animated terms. In response to studies showing the county’s aquifer diminishing, the state government placed a moratorium on new groundwater-fed development in the area in 2019. Homebuilders and developers pinned their hopes on Republicans’ proposed reform allowing new development on former farmland, but Hobbs’ veto dashed those dreams.

Stephen Miller, a conservative Republican who serves on the county’s board of supervisors, told Grist that he views the Democrats’ opposition to new Pinal County development as motivated by partisan politics. The Republicans legislators who represent the area voted in favor of the bill that would restart development, but Seaman, the area’s lone Democratic representative, voted against it.

“We’re just sitting back watching because the makeup of the House and the Senate will determine what happens here,” Miller said. “If they’re both taken over by the Democrats, I think there’s probably very little we can do [to relax the development restrictions].”

As Miller sees it, the restriction on new housing is part of a ploy by the state’s Democratic establishment to suppress growth in a conservative area — or even repossess its water.

“It shouldn’t be a partisan thing at all,” he said. “You’d think that they’d all want to pull this wagon in the same direction. But all they want Pinal County for is to stick a straw in here and take our water.”

Another reason for the relative campaign silence on water issues is that the regions where water is most threatened — areas where massive agricultural groundwater usage has emptied household wells and caused land to crack apart — tend to be represented by the politicians who are most dismissive of water conservation efforts, and vice versa. Cochise County, where an enormous dairy operation called Riverview has residents up in arms over vanishing well water, backed Trump by almost 20 points in 2020; La Paz County, where a massive Saudi farming operation has drained local aquifers, backed the former president by almost 40 points. The state representatives from these areas are almost all Republicans opposed to new water regulation; many have direct ties to the agriculture or real estate industries.

Meanwhile, the majority of pro-regulation Democrats in the state legislature represent urban areas that have more diverse sources of water, stronger regulations, and more backup water to help them get through periods of shortage.

The state legislature’s two leading voices on water exemplify this divide. Democratic state senator Priya Sundareshan represents a progressive district in the core of Tucson, where city leaders have banked trillions of gallons of Colorado River water, all but ensuring that the city won’t go dry — and can even continue to grow as the river shrinks.

Sundareshan’s chief adversary is Republican Gail Griffin, a veteran legislator from Cochise County who chairs the lower chamber’s powerful natural resources committee. Griffin, a realtor, has blocked nearly all proposed water legislation for years, preventing even bills from members of her own party from getting a vote. Other legislators and water experts often cite her as the principal reason the state has not moved any major bills to regulate rural water usage — even though the county she represents faces arguably the most acute water crisis of them all. (Griffin did not respond to Grist’s requests for comment.)

Sundareshan, for her part, admits that it’s awkward that urban legislators are trying to set water policy for the rural parts of the state. But she says that Republicans have stalled on the issue for too long.

“It doesn’t look great,” she said. “But right now, rural legislators are setting policy for urban areas. That’s why that’s why legislators like me are stepping up to say, ‘Well, we need to actually solve these issues.’ Water is water, right? And the lack of availability of water in a rural area is going to impact the availability of water in our urban areas.”

The backlash to unsustainable groundwater pumping is not just coming from urban progressives, though — it’s also coming rural Republicans’ own constituents. In 2022, Cochise County voters approved a ballot proposal to restrict the growth of their water usage. (The strictness of the new rules is still being debated.) Even so, there’s no sign that any of these areas will endorse a Democrat. When Hobbs held a series of town halls in rural areas facing groundwater issues last year, she and her staff faced significant blowback from attendees who didn’t want the state meddling in their water usage. This year, elections in these areas are not even close to competitive. Griffin, the legislature’s strongest opponent of water regulation, is running unopposed.

This means that the future of the state’s water policy depends on voters in just a few swing districts that straddle the urban-rural divide: suburban seats on the outskirts of Phoenix and Tucson, where new subdivisions collide with vestigial farmland and open desert. For many voters in these purple districts, Arizona’s water problems are far from a motivating political issue — and likely won’t be for decades to come, as aquifers silently diminish underground. Voters might hear about water issues in other parts of the state, or wince when they see their water bills, but the disappearing water under their feet is all but invisible, and may remain so for the rest of their lives.

This dissonance is best exemplified by the 17th state legislative district, perhaps the most pivotal swing seat in the legislature. The district extends along the northern edge of Tucson, roping in a mix of retirement communities, rural houses, and cotton farms that may soon be replaced by new tract housing. Many of the new developments in these areas, such as the sprawling Saddlebrooke neighborhood, rely on finite aquifers and get water delivered by private companies. To comply with Arizona law, developers have to prove that they have enough water to supply new homes for 100 years, but even that doesn’t guarantee that the aquifers won’t continue drying up.

It’s difficult to interest voters in a groundwater decline that is happening out of view, in a crisis that almost nobody is talking about publicly. The best that local Democrats can do is make a general pitch that water security is a common sense, bipartisan problem that they are committed to solving — without needing to explain how they would resolve complex questions about the interplay between water regulation and economic growth, among other nuances.

John McLean, a former engineer who is running against a conservative legislator in an effort to flip the 17th district, has sought to position himself as a straight-down-the-middle moderate. His campaign literature tends not to mention his party affiliation, but it does tout water as one of his three key policy issues, along with public education and abortion access. The campaign pamphlet he’s been leaving in the doorways of homes in Saddlebrooke argues for a “commonsense approaches to secure our water future” and declares that “we must stop foreign and out-of-state corporations from pumping unlimited water out of our state” — something that has happened in the conservative, rural parts of Arizona, but nowhere near Saddlebrooke and the 17th district.

When I joined him as he knocked doors in Saddlebrooke, McLean told me that he’s found that almost every voter he meets agrees with him on the need for sensible water regulations — a far cry from lightning-rod issues like public safety, abortion, and inflation.

“Everybody is really serious about water independence, and I think that they’re concerned about partisanship,” he said. “I don’t think there’s really much of a partisan difference among citizens when it comes to water.”

That apparent consensus, however, does not extend to the state’s elected officials.

“My Republican opponent voted to relax groundwater pumping restrictions,” McLean, referring to a bill that would have eliminated legal liability for groundwater users whose water usage compromised nearby rivers or streams. “So he was on exactly the wrong side of that one.”