Every spring, Marshall Ganz teaches a class at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government on how to organize a political movement. This year feels especially strange, he tells the assembled room of earnest young students who have packed the classroom to overflowing so that they cover the floor and the window ledges. It’s 2014 — the 50th anniversary of Freedom Summer, which was the beginning both of Ganz’ education and of a theory of political organizing that would, ultimately, be used to help elect the first African American president of the United States.

In 1964, Ganz was 21, and on the verge of becoming a college dropout. He has a way of making not staying in school sound pretty exciting. “It was a movement of young people,” he tells the room. “Do you know how old Martin Luther King was when he led the bus boycott?” He doesn’t wait for an answer. “Twenty-five.”

“I got hooked,” he continues. “Going back to Harvard seemed like the most boring thing in the world. I wrote a pretentious letter: ‘How can I go back and study history when I’ve been making it?'”

Ganz’s father was a rabbi, and Ganz remembers spending his fifth birthday in a displaced persons camp in Germany, giving presents to other children. “My mom,” he tells the students, “had an idea that I should give presents instead of getting them.” To him, the Holocaust was not about anti-Semitism, but racism. “It’s not a complex ideology,” Ganz says. “Racism kills. As a rabbi’s kid I loved the Passover seder. They were like the story of the Exodus, but with food. They point at children and say, ‘You were slaves in Egypt.’ Not you literally — but you have to figure out who you are in this story. You need to figure out if you’re holding people back or helping people through.”

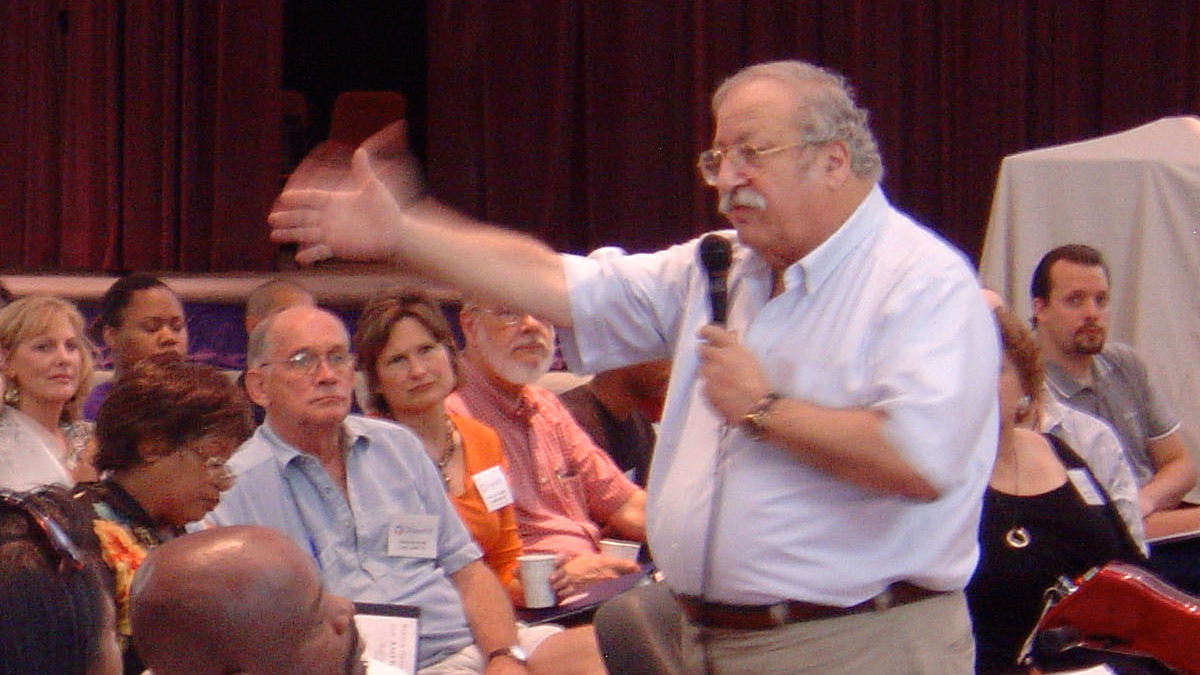

Ganz is disheveled, folksy, and charming. Everything about the talk feels loose, improvisational, off-the-cuff. It’s not. It’s a well-crafted work of persuasion — an attempt to make the craft of shifting the standards of a society into something accessible to anyone.

The talk we’re hearing now is nearly identical to one he gave three years ago, to Occupy Boston. Most of this course is online, as is nearly everything Ganz has written or talked about.

What Freedom Summer taught him, Ganz continues, is how to fight back against a group of people who have rigged the system. “Whites didn’t have power because blacks had granted it. They couldn’t vote! There was no mechanism of political accountability. If you want to understand inequality, look at the power. And then — what do you do? Do you go to Washington, D.C., and say ‘Can I have some of your power?’ They’ll just say, ‘Testify before our committee! Give us some more evidence!'”

The civil rights movement had no such illusions, says Ganz. It was packed with seasoned activists, and was always grooming more. Rosa Parks was a secretary of NAACP, but she also trained at the Highlander Center. Martin Luther King learned from his father, who was a Baptist minister. “You have to be a good organizer to be a good minister,” laughs Ganz. “Otherwise you don’t have a congregation.”

To Ganz, who has spent decades seeing causes rise and fall, the strongest social movements are made of a network, rather than a hierarchy. He illustrates this point with a cartoonishly large Hoberman sphere that he likes to snap open at the end of lectures.

Recently, he sat down with me to talk about how organizing works, where the environmental movement fits in, and how the Sierra Club’s plans evolved into the 2008 Obama campaign.

Q. How was Freedom Summer organized? Did it seem like an especially well-run organization at the time?

A. My first experience was with Dottie Zelner in Boston who was the Friends of SNCC person who first got me involved. She was great. Very together. Then I arrived in Oxford, Ohio — that was where they did the training for Freedom Summer.

We had three programs: the community centers, the Freedom Schools, and the MFDP. It was very clear what everybody was doing. There were loose ends and stuff, but it was pretty exciting. It was like the “eve of battle” kind of thing.

Q. It was like Tolkien.

A. Yeah.

Q. Except now it becomes clear to me that probably none of you had read Tolkien yet.

A. No. But it was very much like the entry into enemy territory. There was fear and excitement and all that stuff going on. Tension of all different kinds. They wanted volunteers for a group to go to southwest Mississippi, which was supposed to be really tough. I wound up volunteering.

Curtis Hayes was our project leader. Now he’s Curtis Muhammed. Hollis Watkins, Jesse Harris. We had this thing like “Oh, we’re special.”

My whole experience of it was really positive. Good leadership. Good focus … [Later,] we began to have frustration with the overall direction, beginning in November, December of ’64.

Q. One thing that I’ve been hearing about the recent environmental movement is that, until Keystone, there really weren’t many short-term goals — just a big amorphous need to “save the planet.”

A. You have to break out strategic objectives. People have had that for a long time — whether it’s closing this coal plant or passing this law. The overarching theme of the Freedom Summer project was to break the resistance in Mississippi. Specifically: to win the right to organize. That was the No. 1 issue. It wasn’t safe to organize.

Bob Moses said, “There are people in the United Sates that the law covers and people that it doesn’t. It doesn’t cover black people in Mississippi but it does cover white people in the north. If you want to bring the law to Mississippi you bring the people the law covers to Mississippi. Then you will bring the law to Mississippi.” Sure enough it did. It was a clear strategy.

The civil rights movement was always a series of campaigns. And there was always a clear objective of some kind. To integrate this place; to open up voter registration in that place. We’re going to desegregate everything in this region; no, we’re going to stick to this city.

There was an ongoing development of targets at regional and state levels that went on between the organizations. Someone would say, “We want to start a campaign in Americus, Georgia.” And so there would be a discussion within SNCC like “Well, can we support that?”

In Mississippi there was a very strategic decision not to mess with public accommodations. Not mess with schools. Not deal with anything until we first won the right to organize and to vote. The voting rights thing was so central.

The strategy was very much an ongoing development. It was anchored in what the capacity was. The march on Washington, for example, was a national tactic, and that was seen as part of what had evolved as a national strategy with regard to the Kennedy administration. By that time there was a leadership conference on civil rights. There was SCLC, SNCC, CORE, NAACP, Urban League. Different organizations pursuing different strategies on local levels. That was a convergence, like “everyone is going to focus on this one thing.”

The key point was that it wasn’t just spontaneous. People were making choices about what things to take advantage of, and what things to initiate. There was always a pretty intense dialogue about what was happening. Things would move fast or slow. There’s a rhythm to it. But everyone pretty much understood that the movement consisted of campaigns. And these campaigns had to have a focus. The focus would vary depending on where the action was.

The Summer Project was about winning the right to organize, and that took the form of organizing for the Freedom Democratic Party — creating this parallel organization to the regular Democrats and then going to Atlantic City and challenging the Mississippi Democrats to be thrown out so that our people could be seated. That was part of the national strategy pressuring the Democratic party around voting rights. The following year it turned into a variety of different approaches until the Voting Rights Act.

And once the Voting Rights Act got passed, everyone was trying to get their county to be federalized — so that people could start to register to vote. That’s what we did. It was always very purposeful.

Q. And then you went out to Bakersfield and worked with Cesar Chavez.

A. And that was also very strategic and outcome focused.

Q. Until it wasn’t, and it got founder’s disease.

A. It got founder’s disease. But it was even clearer than the civil rights movement, because it was one organization. And so there was a clear way of making decisions.

The grape strike was forced upon Cesar and his buddies. It was something the AFL-CIO initiated — actually sort of to call Cesar’s bluff. He wanted to organize for five years before trying anything. The preliminary organizing was about building relations between the people and building the organizational infrastructure. And that was through a credit union, newspaper, social services, death benefit — all that kind of stuff. He thought that needed to be done in order to sustain a strike — that the error in the past had been striking and organizing at the same time. That didn’t work.

Now the AFL-CIO had a competing organization, called AWOC — Agriculture Workers Organizing Committee. And it was going nowhere. But they did have the support of Filipino workers, which were these specialized grape packing crews. They were the ones who actually initiated the grape strike.

And then Cesar’s group, who represented mostly the Mexican workers, had to decide if they were going to be strikebreakers or not. They were forced into it. But once they were forced into it, they took the leadership of it. Frank Bardacke’s book is very good, if you’re really interested in the nuts and bolts of organization. I focus on the first three years and how the whole thing got going because I’m developing a theory of strategy. Frank focuses on how the organization of work worked, and how the union interfaced with that.

The trouble is that a lot of these books for a long time were being written by people who didn’t speak Spanish. They couldn’t talk to workers, and only talked to the organizers. But Frank’s was good. He worked in the fields for a while.

Q. And then later you became involved in the environmental movement. What was that like?

A. I first started doing stuff with the Sierra Club in, I believe, 1989. I did some organizer training there with Carl Pope and then was involved in something called “Big Green.” It was an environmental ballot initiative. Then, in 2003, I was asked to go to a Sierra Club executive board meeting and talk about movements: what works, what doesn’t work. In the middle of the presentation, a couple things happened.

One of them was that I asked, “Which of your local chapters work and which of them don’t?” They didn’t know.

I said, “Well, one way would be to find out which ones are working and see why they’re working and maybe that’ll help you get a picture of how the ones that aren’t working aren’t.” They said, “Oh, we can do that?” And I said, “You can design a research project to do that.”

And another thing that came out: I was talking about the role of conventions in traditional national organizations. They brought local leaders together at a state level, state leaders together at a national level. They broadened people’s understanding and interest. It wasn’t so parochial. So one of the trustees stood up and said, “We’ve never had one of those. Sierra Club never had a convention. If the board decides to have one, I’ll put up the first $100,000 for it.” That was a compelling argument.

So two things came out of that meeting. One of them was a research project that we started — it was a three-year research project. And the second was a convention, called the Sierra Summit. Basically, there was a deep divide between the volunteer leadership and the staff leadership. Sort of a wish for command and control on the staff side, resentment on the volunteer side. No real training. No real leadership development.

And so what we found was that the local groups that had recreational components actually tended to be healthier because the recreational leadership tended to be more collaborative than the political leadership, at the chapter level. And the political leadership tended to be very individualistic and very non-collaborative. So where we found ExComs [executive committees of local chapters] that had a lot of interdependence and teamwork, they tended to function much better than those that didn’t.

So they had their first convention, which was wonderful, but they never had a follow-up. We did a second round of research working with 20 local groups and four state chapters in how to turn their Excoms into functional Excoms. We developed a framework.

The Sierra Club didn’t actually do much with what we came up with. It was frustrating — all these people had been hung up on this problem, but the staff leadership couldn’t let up control.

But — one thing that came out of that. The framework we used? We later used it in Camp Obama [organizing volunteers for the 2008 presidential campaign]. That was the incubator.