Every year representatives from nearly every country on earth assemble to find a way to keep the planet from melting. Every year hopes soar for an agreement that will wrestle emissions to zero. And every year those hopes are dashed.

This year’s United Nations Conference of Parties on climate change in Glasgow, Scotland, will be no different. The rhetoric is already far bigger — John Kerry, the U.S. envoy for climate change, called what’s known as COP26 “the last best hope,” for humanity — than anything leaders can deliver. But veteran diplomats and climate wonks say that, despite everything, maybe that’s OK.

Judge this 26th COP on its ability to deliver salvation, and it’s assured to fail. But there’s a lot negotiators from nearly 200 countries can do below that unrealistically high bar, by building on the 2015 Paris agreement (a result of COP 21) and increasing communication and cooperation. And though that might sound like weak tea, it’s vastly better than the alternative, in which every country stubbornly goes its own way, and disputes are resolved in the old-fashioned method — war.

“My measure of success is the simple progress, and not falling apart,” said Andrew Revkin, who, after years covering these U.N. gatherings as a journalist, now leads initiatives on climate change communication at Columbia University’s Earth Institute. “This is just a check in on a 100-year process.”

Of course, it’s more dramatic to think of the conference as a make-or-break moment, which is why activists, politicians, and journalists often frame it in that way. But when these speakers are being careful, they hedge a little. That’s why Kerry called COP26 not “the last hope,” but the “last best hope.” Because every passing moment is technically our last best hope: It would have been better to stop emitting greenhouse gasses yesterday than today. And after the current summit fails to stop emissions in one fell swoop, the following year will, again, be the last best hope.

Perhaps inflated rhetoric comes with the territory. Daniel Raimi, a fellow at the nonprofit Resources For the Future in Washington, D.C., understands why politicians imagine these giant gatherings as caped superheroes, capable of thwarting climate change.

“I have two competing narratives in my head. One is the ambitious narrative that says we need a superhero moment – because we do need that, that’s definitely clear,” Raimi said. “On the other hand, that’s just not the way that global governance processes have ever worked before. We need to recognize the constraints of the political reality, while at the same time pushing to do the best we can.”

Why can’t the COP swoop in and save us?

There’s a simple reason that experts think this gathering cannot force radical change onto the world: It operates via consensus. Any single member of the 199 countries meeting in Glasgow can derail the whole process by saying, “no.” The United Nations can’t strong-arm the world’s biggest polluters, China and the United States — or even tiny Lichtenstein — into reducing emissions.

Negotiators also just don’t have that much latitude even with their own governments. They can’t strike an ambitious deal to, say, shut down the oil industry, and then come home and impose that decision on their country. If Saudi Arabia, the world’s largest oil exporter, abruptly stopped producing fossil fuels, it would likely collapse. That helps explain why the monarchy has set a date of 2060 to go “net zero,” a decade after the widely accepted goal. Each government is limited by its own economic reality and political processes.

“For many countries, acting will result in domestic economic and political pain,” Raimi said. The residents of the world’s largest oil and gas producer – Americans – should be intimately familiar with the challenges of enacting climate policy when many elected representatives benefit from fossil fuels, he said. Even when the majority of a country wants climate action, they are often constrained by things like senates and constitutions.

For these reasons, it’s not accurate to think of COP as the superhero that can bend the ever-rising emissions curve downward in a single display of muscular heroism. Instead, think of it as the place countries officially enshrine the policies they have already determined will serve their interests.

“The treaty process tends to memorialize, rather than determine, what’s possible,” Revkin said.

What about the Montreal Protocol?

When people look for hope in international agreements, they often look to the ozone layer. In 1987, countries negotiated the Montreal Protocol, and it’s no exaggeration to say it saved the world: If the ozone layer had collapsed, life as we know it would have become impossible. Every single country ratified the agreement. The treaty’s success proves that countries really can work together to reengineer the composition of the Earth’s atmosphere.

But the Montreal Protocol wasn’t imposed on the world, like a top-down edict. The United Nations didn’t dispatch blue helmets in black helicopters to rip the refrigerators from protesting nations. It was bottom up: DuPont, the world’s largest manufacturer of ozone-destroying chemicals like Freon, came to the table and shaped a plan to switch the world over to a new set of refrigerants it had developed that wouldn’t wipe out the ozone layer.

“The Montreal Protocol succeeded in part because it asked so little of us, the public,” said Steve Montzka, a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration scientist who regularly presents data to U.N. conferences focused on ozone. There were alternative chemicals readily available. So people didn’t have to give up their air conditioners or go back to cooling refrigerators with ice. The industries involved were able to continue operating and making profits.

“In my opinion, the COP can’t provide the motivation to solve the climate crisis, that has to be found beforehand and brought to the meeting,” Montzka said.

So what’s the point of this COP?

There’s a lot the gathering in Glasgow can do, even if it can’t reverse the world’s greenhouse gas emissions overnight.

Because climate change is a global problem, efforts to eliminate emissions can be frustrated by, say, Russia flipping the bird at future generations and going on a coal-burning spree. Agreements rest on the faith that eventually everyone will do their part. The U.N. provides the framework for organizing countries and the COPs are the meetings for maintaining that faith.

“What’s crucially important is that by getting these high-profile agreements you create legitimacy and direction for the entire effort,” said David Victor, a professor of innovation and public policy at the University of California, San Diego. Without these meetings, he said, “it’s much, much harder to see how we would have been able to put as much pressure on governments and on firms to do things in a highly decentralized way that, overall, actually add up to a pretty significant effort.”

These U.N. conferences play a vital role, just not the kind of role that would get a speaking part in the Marvel Cinematic Universe. It’s all about building a system of climate governance and chipping away at the problem of climate change in dozens of small ways. It’s mostly “stuff that is bad for journalistic hooks but good for building a foundation,” said Morgan Bazilian, a professor of public policy at the Colorado School of Mines, who has attended U.N. climate summits as a lead negotiator for the European Union.

Specifically, negotiators can reach agreement on ways to monitor emissions. They can set up a system to disperse money to developing countries that haven’t had the chance to get rich off fossil fuels, but are already bearing the brunt of climate change. They can improve the rules around international carbon markets to make them legitimate and transparent. The conference can provide a venue for smaller groups of countries to collaborate on schemes to cut back their methane emissions, and for industries to figure out how to cooperate in their efforts to make emissions-free steel and concrete.

How to read a COP

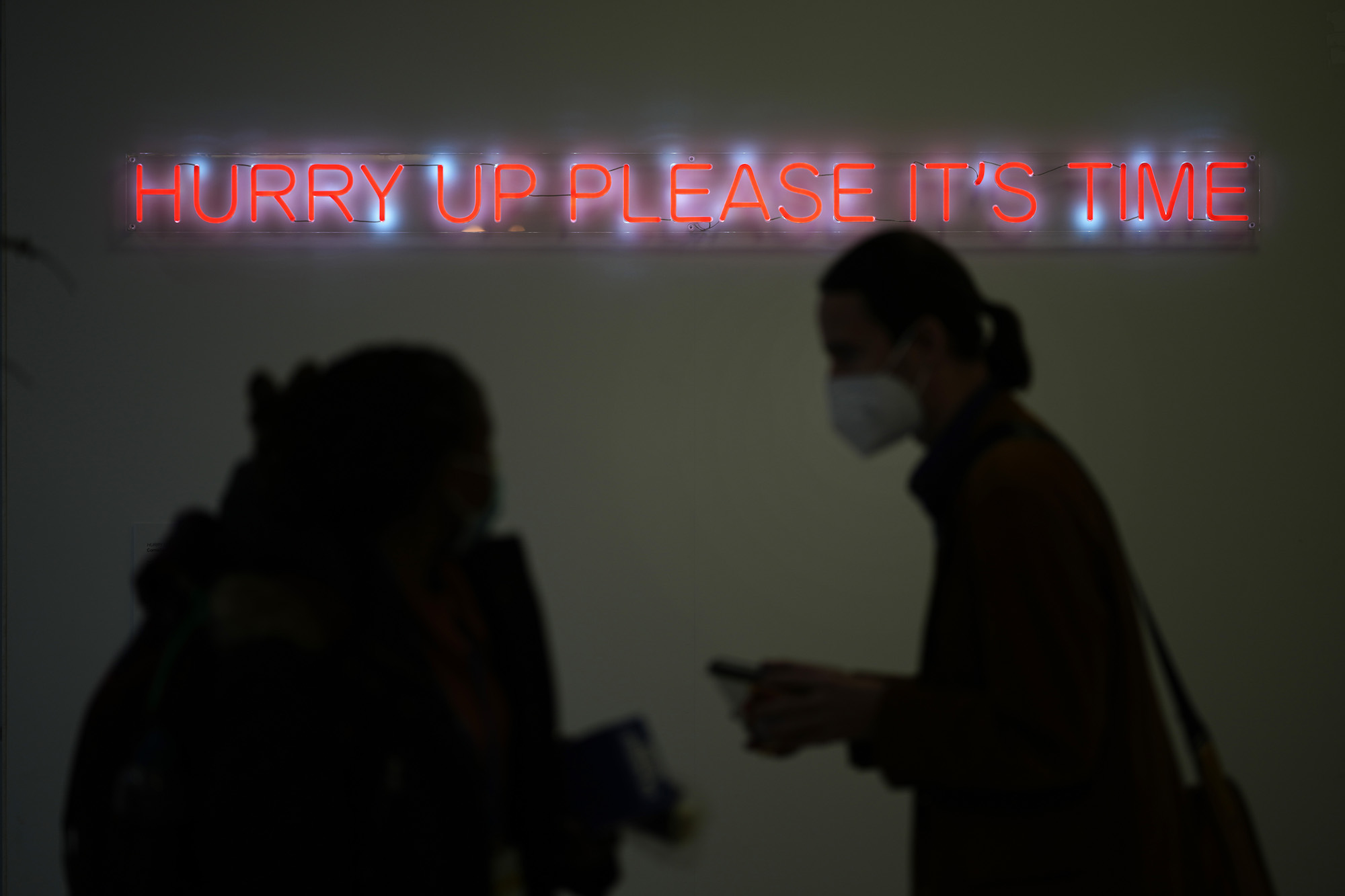

You can expect a lot of flash at the conference in Glasgow. Prince Charles made an appearance on Monday to warn of “an existential threat” like the COVID pandemic. Arnold Schwarzenegger, Bill Gates, and Jeff Bezos are there. There will be marches and activists giving rousing speeches. Environmental nonprofits will release reams of new reports while businesses and world leaders play up their latest initiatives. Media organizations from around the world will send journalists to find out if this time, the climate summit is going to save the world.

Bazilian worries that the hype could undermine the arcane but important work done at these meetings. “If you continually build up a narrative that something magical is going to happen and nothing magical happens, eventually it has an effect,” he said.

As you watch the news come out of this U.N. gathering, remember: What matters is that countries keep finding more reasons to collaborate and to keep updating their carbon-cutting plans. Perhaps they will help coal-dependent countries like India shut down coal plants or develop a better way to funnel money to poorer countries. If the resulting agreements help save the world, Bazilian said, it will be through those baby steps, repeated hundreds of times, not through stirring oratory. “Let go of the hype and platitudes and get to work,” he said.