This story was originally published by Mother Jones and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Food and agriculture policy has been at best a fringe issue during the last few Democratic presidential primaries. Candidates tend to limit their agricultural appeals to “broad value statements” rather than dive into the policy specifics “that would indicate they’ve given these issues the attention they deserve,” says Sarah Hackney, coalition director for the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition.

This cycle is different. Corn and soybean farmers are locked in a multi-year slump, made worse by President Donald Trump’s trade wars. Dairy farms in Wisconsin are failing at the rate of two per day. And climate chaos has pounded farm country in recent years, from California’s vicious mid-decade drought to the soil-destroying bomb-cyclone storms that slammed the corn belt this spring. As talk of global warming permeates the debate, so does acknowledgement that agriculture contributes at least 10 percent of the world’s greenhouse emissions.

But farming can also play a huge role in dialing back climate change. Two frontrunners have released detailed, and quite radical, agriculture-policy agendas; and several Democratic hopefuls regularly mention the topic when they’re discussing climate change.

One of the most popular ideas coursing through the campaign rhetoric is paying farmers to grow crops and raise livestock in a way that pulls carbon dioxide out of the air and traps it in soil, thus helping stabilize the climate, a practice widely called “regenerative agriculture.”

In the latest episode of Bite podcast, Mother Jones climate reporter Rebecca Leber and I compare notes on the nuances between the Democratic presidential candidates’ platforms. Here’s a summary of six of the frontrunners’ agriculture proposals:

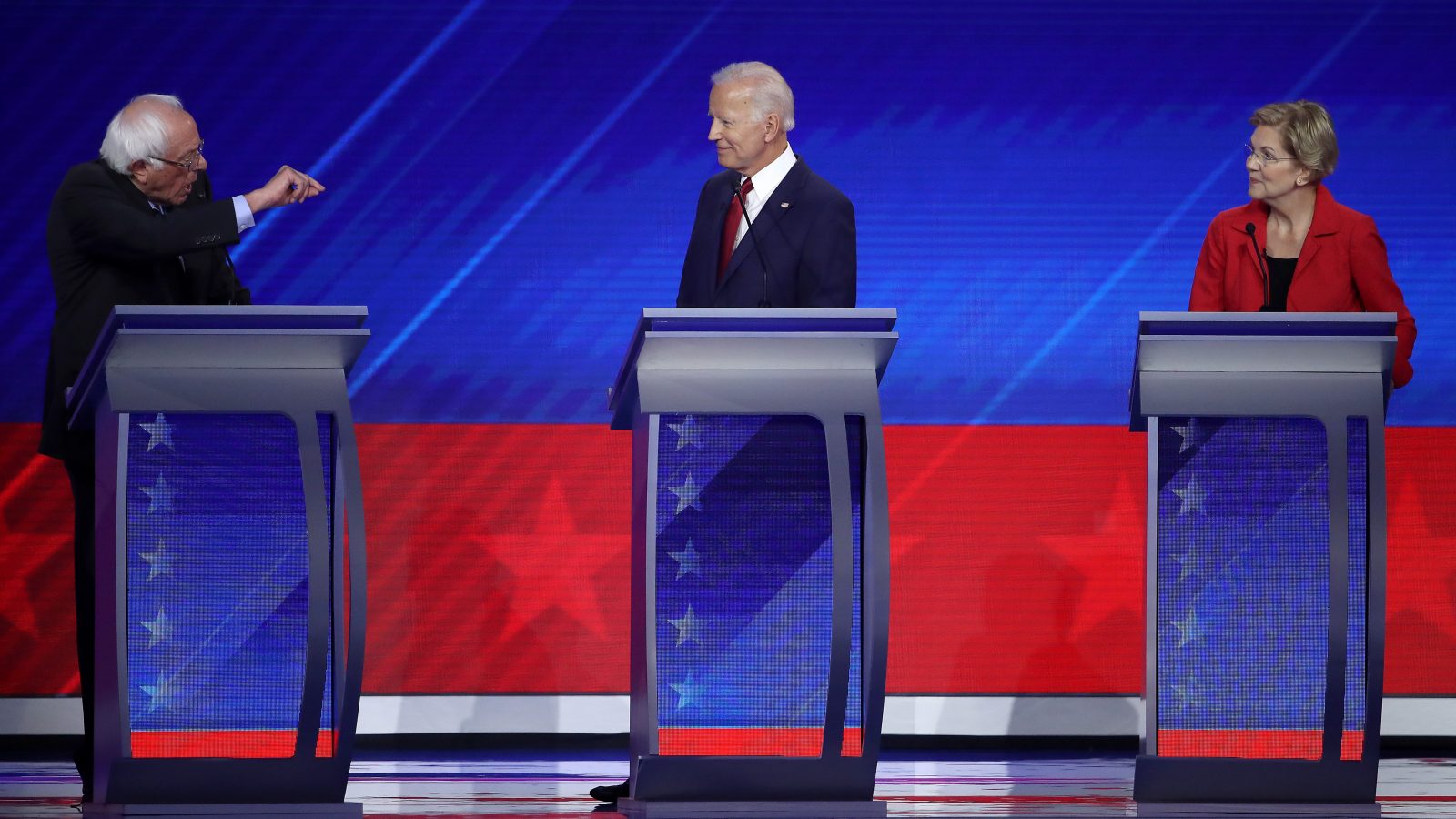

Elizabeth Warren

In a plan released in early August, Warren called for a fundamental reordering of agricultural policy. She proposes to reinstate “supply management” — a New Deal-era set of rules that ensured farmers of major crops like corn, soybeans, and wheat fair prices, by coordinating farmers’ planting decisions and storing any excess grain in government-managed reserves after bumper harvests. To my knowledge, no major candidate since Jesse Jackson in his 1988 bid for the Democratic nomination has proposed it. The idea is to end chronic overproduction, which triggered massive farm crises in the 1930s, the 1980s, and one that’s brewing right now. Supply management started to unravel in the 1970s, and has long since been replaced with incentives for maximum production and the promise that exports would soak up any excess.

Big seed, pesticide, meatpacking, and grain-trading firms hate supply management because they profit most when farmers produce all that they can. But Warren isn’t shy about offending Big Business’s sensibilities; rather, she says she’ll break up the big conglomerates that dominate agriculture. “Under my plan to level the playing field for America’s farmers I’ll use every tool I have to break up big agribusinesses, including by reviewing — and reversing — anti-competitive mergers,” the plan states. She also vows to force the few companies that dominate meatpacking to pay the “full costs of the environmental damage they wreak” from combining livestock together by the thousands in large facilities.

She also proposes to “pay farmers to fight climate change” by ramping up the budget for the Conservation Stewardship Program from $1 billion to $16 billion; and to “expand the ‘Farm-to-School’ program a hundredfold and turn it into a billion-dollar ‘Farm to People’ program in which all federally-supported public institutions — including military bases and hospitals — will partner with local, independent farmers to provide fresh, local food.”

Bernie Sanders

Soon after the release of Warren’s plan, Sanders put forward a $16.3 trillion agenda for a Green New Deal, delivering a detailed vision of the climate change-fighting policy framework proposed by Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Senator Ed Markey earlier in the year. Sanders’ Green New Deal plan contains a heavy dose of food policy reform — in ways that match and even exceed Warren’s grand designs. Like Warren’s ag plan, Sanders’ document calls for a return to supply management and the “break up of big agribusinesses that have a stranglehold on farmers and rural communities.” And it commits a dramatic $410 billion over ten years to “help farms of all sizes transition to ecologically regenerative agricultural practices” geared to “both sequestering carbon and increasing resiliency in the face of extreme weather events.”

The cherries on top: $36 billion over 10 years for a “victory lawns and gardens initiative” to “help urban, rural, and suburban Americans transform their lawns into food-producing or reforested spaces that sequester carbon and save water”; and $14.7 billion to invest in “cooperatively owned grocery stores,” with a focus on low-income areas.

Joe Biden

The former vice president’s plan is considerably less transformative than those of his two main rivals; Biden proposes no reforms to current farm subsidy programs. Like Warren and Sanders, he vows to “dramatically expand and fortify” current federal programs that pay farmers for environmentally sustainable practices, but he doesn’t specify by how much. He suggests a kind of public-private partnership to help the agricultural sector become carbon neutral. Under his plan, “corporations, individuals, and foundations” will be able to “offset their emissions” by contributing to a federal fund that pays farmer to store carbon in soil. While Sanders and Warren promise to break up agribusiness giants, Biden commits himself only to “strengthening antitrust enforcement.”

Pete Buttigieg

As much as any candidate running, the South Bend, Indiana, mayor mentions farming when he talks about addressing climate change. In a recent interview with the Climate Desk and the Weather Channel, Buttigieg argued that climate policy has to include inviting farmers to “be part of the solution … we should be funding and supporting them in sustainable agriculture practices.” His rural policy platform promises to “significantly invest in R&D as a powerful solution to climate change, including through soil carbon sequestration” and “pay farmers to maximize land conservation, biodiversity, productivity, and soil health.”

Cory Booker

In September, the New Jersey senator sponsored a bill called the Climate Stewardship Act. “Inspired by measures implemented in President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal,” Booker’s proposal doesn’t mention the Green New Deal. But it does contain some juicy ag-policy tidbits. It would “support voluntary climate stewardship practices on over 100 million acres of farmland,” by paying farmers for “stewardship practices such as rotational grazing, improved fertilizer efficiency, and planting tens of millions of new acres of cover crops,” which sequester carbon and protect otherwise-bare farmland from soil erosion caused by spring storms.

Like Warren and Sanders, Booker has shown an appetite for taking on Big Ag conglomerates. In 2018, he sponsored a bill that would place an 18-month moratorium on mergers of large food and ag companies, because, he argued, these giant companies are “squeezing small family farmers, driving down wages for workers, and hurting rural communities.”

Kamala Harris

The California senator’s climate plan includes a vague reference to ag policy: She promised to partner with farmers to develop “the regenerative agricultural systems the world needs to provide food, fiber, fuel, and environmental service to 10 billion people.” More impressively, back in February, Harris took a stand for farm workers, sponsoring a bill that would essentially give them the same overtime and minimum-wage protections won by other U.S. workers in the New Deal era. Julián Castro promotes a similar agenda.