Since taking office, President Joe Biden has re-entered the United States into the Paris Agreement, revoked a key permit for the Keystone XL pipeline, and placed a moratorium on new oil and gas leases on public lands. Republicans in Congress aren’t happy. This week, Republicans signaled how they aim to block Biden’s agenda — and what the right’s vision for federal climate action might look like.

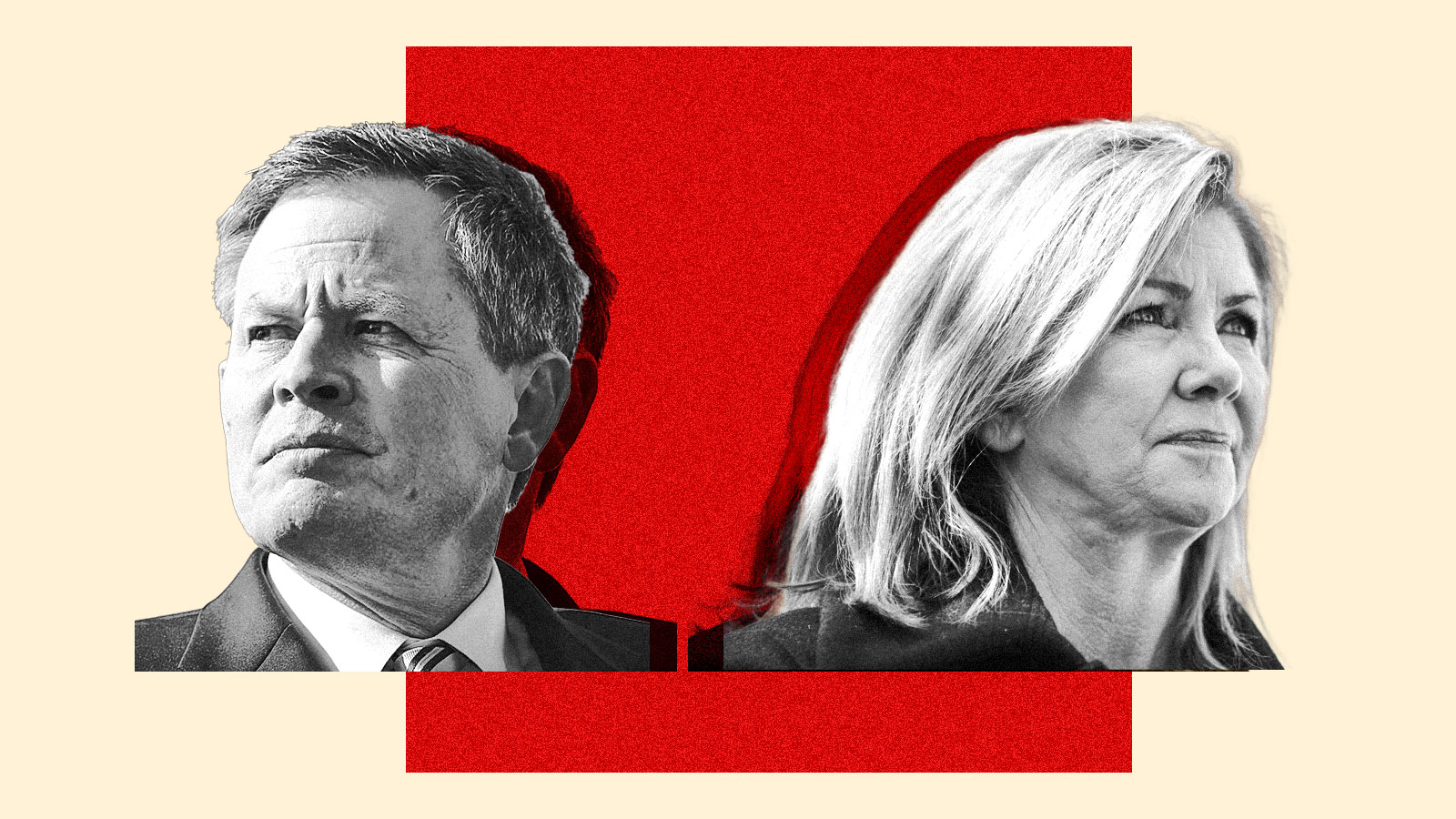

On Monday, two Republican senators, Steve Daines of Montana and Marsha Blackburn of Tennessee, unveiled two measures aimed at undercutting the Paris Agreement. The first, a resolution officially introduced by Daines, says the president should “submit the Paris Agreement to the Senate for review and consideration.” The text of the resolution says that the president can only enter into a treaty if two-thirds of the Senate supports it. The second, a bill introduced by Blackburn, would prevent tax money from being used to rejoin the Paris Agreement. “This bill and resolution will ensure not a single dime of American’s hard-earned money goes toward the Paris Climate Agreement,” Senator Roger Marshall from Kansas, a cosponsor of the bill, said in a statement.

It is highly unlikely that either measure will get much airtime in the Senate, chiefly because Democrats control the upper chamber and get to decide which bills do and don’t get taken up. But, Democratic majority aside, the senators’ measures don’t have a future in the Senate because they don’t make any sense. “The basis for each of these actions is just wrong from a policy standpoint,” Roger Pielke Jr., professor of environmental studies at the University of Colorado Boulder, told Grist.

The resolution is predicated on a constitutional requirement that says presidents can’t enter into treaties without the Senate’s support, but the U.S. has never engaged with the Paris Agreement as a treaty. President Obama joined the accord via executive order, President Trump withdrew using the same method, and President Biden re-joined the agreement last month via, you guessed it, executive order. “In the imaginary world where this would be adjudicated, say in the courts, there’s no way it would be understood as a treaty,” Pielke said.

The bill preventing taxpayer dollars from being used to rejoin the agreement is also offbase. The Paris Agreement is an “agreement to agree,” Pielke said, which means no American dollars are actually funding the thing itself. Money will come into play domestically in the U.S. if legislators pass bills aimed at helping the nation meet its emissions-reduction targets under the Paris Agreement. And the U.S. has already paid approximately $1 billion into the United Nations Green Climate Fund to help poor nations deal with the consequences of climate change, but there is no financial requirement of joining the Paris Agreement in general. “Somebody says we’re going to cut funding for Paris, it doesn’t even mean anything because there is no such thing,” Pielke said.

For Quillan Robinson, vice president of government affairs at the conservative environmental group the American Conservation Coalition, the Daines and Blackburn legislation is a missed opportunity. “What I would like to see is for Republicans to criticize the Paris accord and say, ‘This is not actually an effective measure,’ and then propose what we are going to do,” he said. “Because, as we know, a vast majority of Americans want to see climate action.”

Some Republicans are coming up with a climate strategy beyond obstructing Biden’s agenda. Last weekend, two dozen House Republicans attended a secret climate summit in Salt Lake City, Utah. The point of the summit was to begin formulating a Republican response to rising temperatures. Outside groups including the Heritage Foundation, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the Audubon Society, and the American Conservation Coalition, the group Robinson works for, held events to educate members of Congress on climate and environment issues.

The summit was attended by Republicans who have been involved in climate policy at the federal level before as well as representatives new to climate change. Garret Graves of Louisiana, the top Republican on the House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis; David McKinley of West Virginia, who introduced carbon sequestration legislation last Congress; and Blake Moore of Utah, a political newcomer, were among the 25 representatives in attendance. The Washington Examiner, which first reported the secret summit, said that representatives did not come away with a detailed policy plan, but Bruce Westerman of Arkansas, one of the organizers of the event, “promised future legislative action.”

On the Senate side, Mitt Romney from Utah, who has signaled he’s open to a carbon tax in the past, gave his strongest endorsement of such a pricing mechanism to date in a virtual event with the New York Times on Tuesday. “I’m very open to a carbon tax, carbon dividend, where there’s a tax on oil companies and coal companies and so forth,” Romney said. Lisa Murkowski, another moderate senator, has said she’d be open to a carbon tax too. It’s “worth putting on the table,” she said last October. Meanwhile, the incoming chair of the Senate Agriculture Committee said the committee will take up the Growing Climate Solutions Act, a bipartisan bill introduced by Senator Mike Braun of Indiana last Congress that would help farmers sell carbon credits into carbon trading markets, and move it to the Senate floor for consideration.

Pielke reads these developments as hopeful signs that Blackburn and Daines aren’t representative of the entire GOP. “If the Marsha Blackburns of the world are distracted by the shiny object of Paris and meanwhile more serious efforts are done trying to build support for policy that’s fine, let them have their dead horse to beat,” Pielke said. He’s more focused on moderates in Congress who may soon be ready to reach across the aisle on this issue. “The reality is, if we’re to succeed, we’re going to have to put forward policies that can get substantial bipartisan support,” he said.