You know what a park looks like. It’s a green place, full of grass and trees, that lets people enjoy nature. And you know what a national park looks like: bigger, and even more naturey, than a city park. Except you don’t, apparently, because virtually every leading New York politician is calling on President Obama to create a national park that would be little more than a street corner.

Technically, what they want is a national monument, which like national historic sites and national seashores and so on falls under the National Park Service’s jurisdiction. The corner in question is on Christopher Street, in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village. Long identified with New York City’s gay community (although no one but bankers and movie stars can afford to move there now), the neighborhood incubated the modern gay rights movement. Specifically, at the Stonewall Inn, a bar on Christopher Street, in 1969, patrons fought back against a violent police raid. The surrounding streets featured protests and riots in the days that followed. In 1970, on the first anniversary of the Stonewall riot, the first LGBT Pride march in U.S. history started on Christopher Street.

But the Stonewall Inn is a bar. How do you make a park out of a bar? You don’t. Rather, you turn the sidewalk in front of it and the city-owned pocket park across the street into a national park. Christopher Park — a fenced-off little garden with a bronze statue of Civil War general Philip Henry Sheridan and an oval of half a dozen benches — looks only slightly more like a national park than the bar itself. It is best known to most New Yorkers as a respite for the homeless. “That park that all the bums fill up?” said a friend of mine upon being told the subject of this story. “That’s amazing. I used to see a shrink near there and I’d never wait in that park. I’d rather stand on the sidewalk somewhere.”

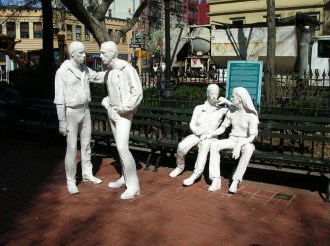

So would a physical monument to honor the gay rights movement be erected there? Not necessarily. A national monument is first declared, then designed. A physical monument could be proposed beforehand, but it hasn’t been yet. For one thing, the park already features two white statues depicting gay and lesbian couples, and the intention is to keep them. For another, space on the site is extremely limited.

So if the national monument status is merely notional, why bother with it at all? The answer is partly bureaucratic and partly philosophical. Bureaucratically speaking, it would move management of Christopher Park from the New York City Parks Department to the National Park Service. “What that does is it brings the storytelling and historic interpretation capacity and, frankly, brilliance of the national parks department to the gay rights story,” says Cortney Worrall, northeast regional director for the National Parks Conservation Association, an advocacy organization focused on protecting and enhancing national parks.

The National Park Service manages many sites that are primarily about historical storytelling — battlefields, for example — and so it would be well-positioned to do the same with gay rights on Christopher Street. It might lead walking tours of the neighborhood, or create a mobile app with a self-guided walking tour. It might post new signage that more dramatically tells the story of what happened in the area; currently there is only a small sign hidden behind a bench. There are precedents for this kind of national monument. Little Rock Central High School, in Arkansas, is a national historic site because of its high-profile role in school desegregation, but it has not been turned into a museum. “The high school still functions,” notes Worrall. “The park service does tours in the high school while kids are in class. What happened is interpreted outside of what you would consider a normal parklike experience.”

On a more philosophical level, creating a national monument — however abstract — would demonstrate national reverence for the achievements of the gay rights movement. The civil rights movement has the Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail in Alabama, and there is a Women’s Rights National Historical Park in Seneca Falls, N.Y. The fight for gay rights deserves the same recognition.

And by creating the park, you open the possibility of it growing into something more physically substantial over time. The New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park is dispersed over 13 blocks in the center of New Bedford, Mass. It has grown since its founding in 1996 to include buildings that now serve as a museum and a visitor center. National parks, says Worrall, “evolve into their final or best existence. The hope is that the designation happens and that’s a catalyst for fundraising to acquire another location in Greenwich Village that serves as a visitor center and archives of the uprising.”

So what happens now? Rep. Jerry Nadler (D-N.Y.), the congressman whose district encompasses the neighborhood, has joined with Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.) in introducing a bill to create the Stonewall national monument. National parks and monuments can be created by an act of Congress, but the current Republican-controlled Congress is about as likely to create Stonewall National Monument as it is to pass a carbon tax.

The president also has the authority, under the Antiquities Act of 1906, to create national monuments by presidential proclamation. Don’t expect President Marco Rubio to do that in 2017 either. Even though Nadler and Gillibrand introduced a bill, their realistic hope is that President Obama will designate the monument while he’s still in office. “President Barack Obama has advanced the arc of gay rights and the last 17 months that he is in office provides a window,” says Nadler spokesman Daniel Schwarz. We’ve seen that national monuments can be well-integrated into the urban fabric, and it seems fitting that America’s first urban president in a century could create this one.