Ghosts of Polluters Past

As new soil tests reveal the pervasiveness of lead contamination, one California barrio continues its long struggle for justice.

By Yvette Cabrera Jan 13, 2022 This project is published in partnership with Voice of OC.

The hot, dry Santa Ana winds that whip through Orange County’s Logan barrio are fierce and temperamental. In the mid-20th century, they’d deliver gusts forceful enough to wreak havoc throughout the Southern California region, destroying orange crops, uprooting trees, downing power lines, and upending lives. But in the Logan neighborhood, one of the city of Santa Ana’s poorest barrios at the time, children like Cecelia Andrade Rodriguez eagerly awaited the wind’s arrival in the fall.

On days when the winds rushed through Logan, Andrade Rodriguez and her friends would race to gather carton barrels discarded by a business in the neighborhood, which at the time was squeezed between a pair of railroad tracks and adjacent to the Interstate 5 freeway. She remembers how she’d drag a barrel to the fence in the Logan Elementary School yard, then crawl into the tube and wait for a gust of wind to blast her across the playground. The children sailed as far as the winds would take them, letting their imaginations carry them to places that they couldn’t go, outside the boundaries of this tiny barrio, home to generations of Mexican Americans who helped build the city.

Logan has been described as the Plymouth Rock of Santa Ana, a predominantly Latino city now home to about 335,000 people, because it’s where the city’s earliest Mexican and Mexican American residents settled. But it’s also an apt analogy for a barrio that has weathered many storms — political battles that the Andrade family and generations of Logan residents have fought in order to defend their homes against the industrialization that surrounded and eventually infiltrated their neighborhood. They would eventually win many of those battles, against the odds. Despite those efforts, the development of the barrio would leave a toxic legacy that still plagues them to this day.

There was a time, in the 1970s, when a proposed extension of one of the city’s busiest thoroughfares, Civic Center Drive, was slated to cut through the heart of Logan and split the barrio in half. Led by Andrade Rodriguez’s mother, Josephine “Chepa” Andrade, who was born and raised in the barrio and served as spokeswoman and president of the Logan neighborhood association, residents went to war against the city and eventually blocked the extension. A parcel of land that was saved by the effort was subsequently christened “Chepa’s Park.”

It was the first of many battles — fought first by Chepa and then by her son Joe, Andrade Rodriguez’s younger brother and the current neighborhood association president — where residents faced off with the city to preserve the soul of their community.

So firmly rooted in the life that the barrio offered its residents, families like the Andrades lived and died on this land — in some cases literally on Logan’s streets, where Chepa’s father suffered a fatal heart attack while walking home from work. Logan offered not just familial ties, friendship, and support, but also a respite from the racism and discrimination that Mexican Americans faced in other parts of Santa Ana, which was once segregated across social spaces like movie theaters, where Mexicans were forced to sit in the balconies. Uptown neighborhoods used racially restrictive covenants in residential deeds to prevent Mexicans and other people of color from living in the city’s most exclusive neighborhoods.

Located on the easternmost edge of Santa Ana, Logan was often overlooked when it came to city services. While the city’s strictly residential tract home neighborhoods had ample backyards and wide, paved streets, these were largely absent in Logan and other working-class Latino barrios in the industrial sections of town. Neighborhood residents relied on ingenuity to make neighborhood improvements — for example, covering Logan Street with apricot pits in the early 20th century to tamp the dust and cover holes in the road. Then, in the early 1930s, the barrio petitioned the city to pave its two primary thoroughfares, Logan and Stafford streets, but was forced to raise the money to cover the cost. The residents ultimately celebrated the paving of their roads with a street dance.

Most Logan families survived on meager earnings, and life along the railroad tracks was never peaceful. Picture frames hung askew on living room walls due to the constant rattle of the trains. Over the decades, Logan’s residents confronted racism and discrimination by creating a self-sufficient world within the barrio that offered opportunities for community members: hosting festivals to raise money to build a church, convincing the city to convert vacant lots for the creation of Chepa’s Park where children could play, and calling on the school district to provide busing so students wouldn’t have to cross major intersections to get to class. Parents proudly enlisted their sons in the military during World War II and planted victory gardens to survive the war’s food shortages.

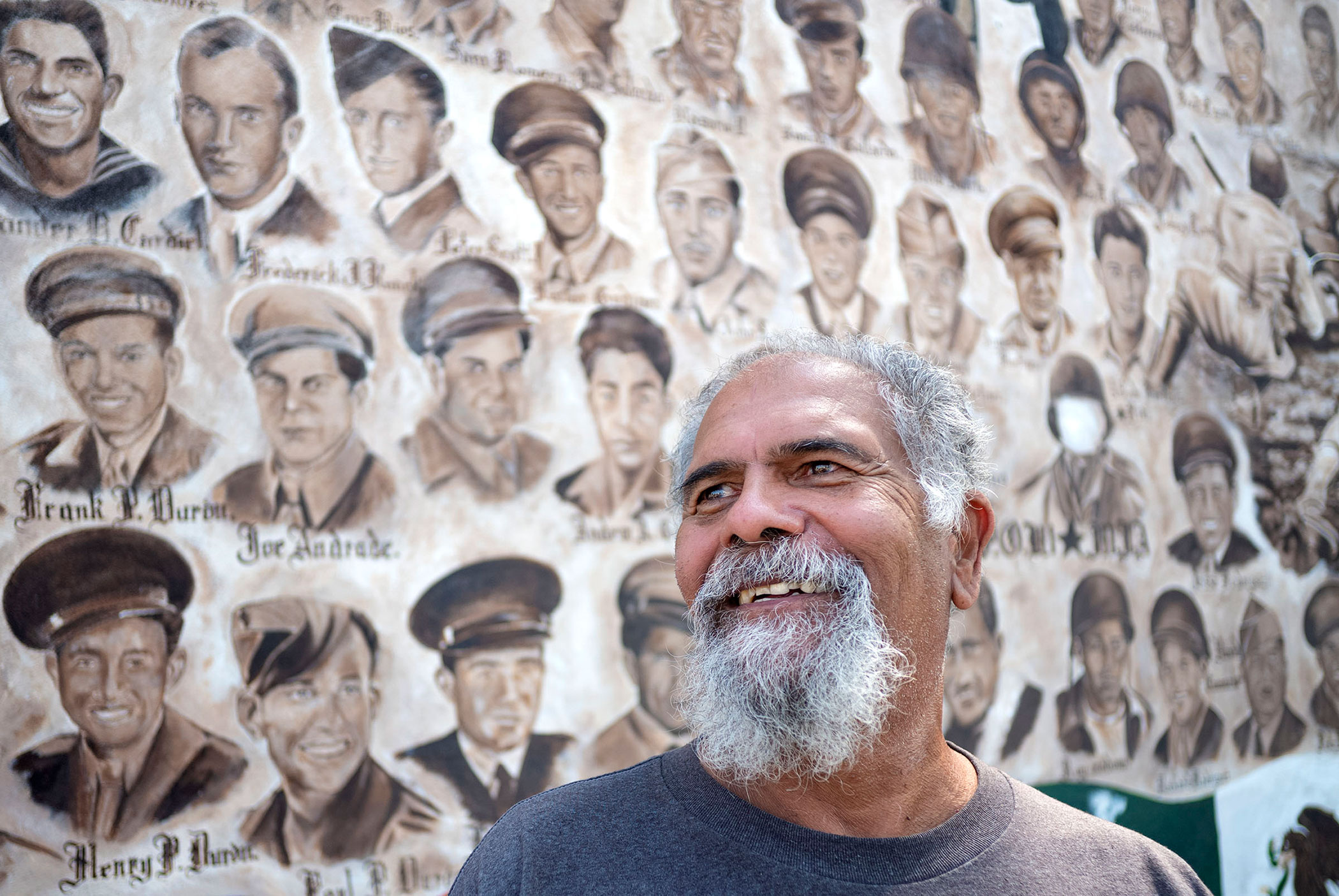

That tradition of neighborhood pride was on full display on a clear, sunny Saturday morning last September, when Logan’s current and former residents trickled into Chepa’s Park for their first reunion since the COVID-19 pandemic began. The reunions have been held annually for more than two decades, and they are above all a celebration that the community has survived the city’s attempts to eliminate the barrio altogether. “We’re Back!!” declared last year’s reunion flyer, which described the barrio as a place “where memories are made and history is cherished.”

“Being born here, right down the street, your heart’s always in it,” Joe Andrade told me last fall. In 2004, Andrade was taken under the wing of one of Chepa’s long-time fellow activists, Logan native Sam Romero, now 87. Together, Romero and Andrade began mapping and tracking neighborhood businesses that they saw as environmental nuisances, calling on Santa Ana to take a tougher stance against firms that violated city ordinances. For example, they fought to regulate an auto paint shop that operated late into the evening, overwhelming the neighborhood with noxious paint fumes as residents tried to sleep.

It was the first of many battles the two men would fight together.

At the reunion, one of Chepa’s best friends, Helen Parga Moraga, sat at a picnic table with Andrade at her side as he ticked off a list of recent victories he and Romero had secured from the city, including installing speed bumps residents had been requesting for 50 years for along several highly trafficked streets. Soon, Lincoln Avenue, near where the Santa Ana winds once swept Cecelia Andrade Rodriguez away in her carton barrel on the Logan playground, will get a major facelift with new sidewalks, curbs, and sewer lines, as well as artificial vines to cover the chain-link fence that now serves as a barrier between the street and the railroad tracks.

Nothing could have pleased Parga Moraga more than to see her best friend’s son take over where his mother had left off in the battle to save Logan. “He’s a fighter,” she said as Andrade described an effort to eliminate congestion on Lincoln Avenue, one of the barrio’s main thoroughfares.

“Oh, I hope I’m alive! I want to see that,” Parga Moraga exclaimed upon hearing the plan. “Really, God give me life until then!”

Andrade told her that every time he fixes a problem in Logan, he remembers his mother and — his eyes glancing upward toward the sky — says: “Another one, mom.”

It’s been nearly a century since the city zoned the already-established residential barrio of Logan for industrial use. Today, the neighborhood’s soil bears the cost of that decision. It absorbed the environmental degradation of each era that thrust Logan into modernity. As the neighborhood’s agricultural roots gave way to industry, products like petroleum, aviation gasoline, lead ore, heavy metals, chemicals, herbicides, and pesticides came and went on the Santa Fe and Southern Pacific railroad lines — but a part of them never left.

The soil would become a repository of proof illustrating how generations of a Mexican barrio were poisoned by lead and other noxious pollutants. Residents knew little about this soil contamination, despite the city’s environmental assessments calling for a deeper exploration of potential lead exposure in the neighborhood in the late 1970s. Comprehensive citywide soil test results were not publicly available until 2017, when I published an investigation that found hazardous levels of lead in the soil in neighborhoods across Santa Ana, which today is Orange County’s second-largest city. To follow up, I conducted hundreds of additional soil tests over the course of 2018 and 2019 in neighborhoods that, like Logan, carried the burden of the city’s industrialization.

More than half of those tests returned lead levels that the state of California considers unsafe for children.

Today, the Logan census tract is identified as a “disadvantaged community” by the state Environmental Protection Agency’s environmental health screening tool because it’s among California’s most pollution-burdened areas. While generations of Mexican Americans battled the encroachment of industry in the Logan barrio and won several major victories, Romero and Andrade concede that they’ve yet to achieve their ultimate goal of restoring Logan to what it once was: a residential neighborhood untainted by industrial contamination. The neighborhood remains filled with scrap yards, recycling centers, auto repair shops, and other industrial and commercial businesses that continue to take their toll on the neighborhood.

“A lot of these businesses don’t care if you get any sleep or not,” said Romero, who recently moved elsewhere in Santa Ana. “You had the big cement trucks running all over the neighborhood, and they’re still doing that. So the quality of life went down the tubes.”

The transformation of Logan from an agricultural, residential hamlet to a barrio surrounded by toxic emissions was no accident. It was determined by city leaders who made zoning and land use decisions throughout the last century that purposefully changed the very nature of Logan and its surroundings. For years, however, the ramifications of those decisions were buried in the dust, leaving residents exposed to soil lead particles that are perpetually resuspended in the air the residents breathe. For years, Logan’s residents have celebrated their history as a barrio, but many never imagined that their past could also come back to haunt them.

As in other urban centers across the country throughout the 20th century, city leaders’ decisions transformed Santa Ana’s built environment, leaving a cumulative legacy of lead contamination in neighborhoods where Mexicans and Mexican Americans were forced by segregation, discrimination, and historical social norms to live during the first half of the 20th century — and where Latino residents continue to reside today.

The fight to restore Logan could one day make the neighborhood healthier to live in, but without a massive remediation effort, the barrio will always carry the stain of its industrial past.

Urban residents in every corner of the U.S. unknowingly live in neighborhoods burdened by toxic contaminants. Most of this residue escaped regulatory scrutiny — the Environmental Protection Agency didn’t comprehensively regulate toxic releases until the late 1980s — and indeed most cities never even bothered to measure these pollutants.

Instead, the work was left to the occasional academic researcher.

In their 2018 book Sites Unseen: Uncovering Hidden Hazards in American Cities, sociologists Scott Frickel and James Elliott outline how the failure to map what they describe as “relic” industrial sites leaves communities in the dark about potential contamination hot spots seeded by businesses that leave behind hazardous byproducts. Using historical industrial directories dating as far back as the 1950s in four American cities, Frickel and Elliott discovered that more than 90 percent of sites where hazardous industry (defined as businesses that perform work known to release toxic chemicals and heavy metals) has operated over the past half-century have become “lost, hidden from view,” and ignored by federal, state, and municipal agencies.

While large polluters such as oil refineries tend to draw the most regulatory scrutiny, Frickel and Elliott’s research concluded that the other types of trouble spots go “unnoticed administratively and legislatively.” They also found that the vast majority of manufacturing facilities and businesses in the directories are small operations with few employees, but they have historically numbered in the thousands in any given city, popping in and out of existence about every eight years on average.

“There is a lot of turnover on these sites, so over time you’re going to get a whole witch’s brew of contaminants,” said Frickel, a professor at Brown University. “You’re going to get different kinds of industry piling on top of one another over time.”

Regulators typically don’t require businesses below a certain size threshold to report emissions. For example, the federal Toxic Release Inventory Program requires reporting from facilities with 10 or more employees that also manufacture or process toxins at volumes greater than 25,000 pounds per year. Thus, according to Frickel, smaller businesses like welding shops tend to fly under the radar. Because the number of historically industrialized sites across the country is so vast — and continues to expand — potentially contaminated soil is a systemic problem, and one that is not being tracked by most regulatory agencies.

Among the most insidious contaminants of this “witch’s brew” is lead. Its use in everything from bullets to car batteries, from aviation fuel to automobile fuel, has allowed it to pervade every aspect of our urban lives and environment — so much so that the social historian Christian Warren has concluded that America’s cities have become “veritable lead mines” as a result. “This lead will not go away by itself — after all, one of the element’s chief attractions has always been its incorruptibility,” he wrote in his 2000 book Brush with Death: A Social History of Lead Poisoning.

A 2018 study published in the medical journal The Lancet estimates that lead exposure is responsible for more than 400,000 deaths annually in the United States, a number that’s 10 times what scientists previously estimated and comparable to deaths attributed to tobacco smoke exposure. The higher mortality estimate was due to the study’s finding that low-level environmental lead exposure has been a largely overlooked risk factor for death from cardiovascular disease, which could be responsible for nearly two-thirds of the deaths attributed to lead exposure.

“It is not surprising that lead exposure is overlooked. It is ubiquitous, but insidious and largely beyond the control of patients and clinicians,” concluded Bruce Lanphear, a professor of health sciences at Simon Fraser University in Canada, and his co-authors in the study.

Five decades ago, Clair C. Patterson, a California Institute of Technology geochemist who pioneered techniques to measure lead levels, warned that legacy lead contamination would come back to haunt cities. He argued that Americans’ blood lead levels were unsafe, and his findings provided key evidence for environmental activists who successfully sought to remove lead from gasoline.

Subsequent scientific research has shown that the use of lead in gasoline, lead-based paint, smelters, industrial emissions, and other factors have led to a buildup of soil lead contamination in the interior of America’s cities over the past century. The phasedown in the use of leaded gasoline that began in the 1970s led to drastic reductions in Americans’ blood lead levels over the past five decades, but scientists warn that blood lead levels still remain unnaturally high.

In 1980, Patterson predicted that much of lead’s damage had already been done. “Sometime in the near future it probably will be shown that the older urban areas of the United States have been rendered more or less uninhabitable by the millions of tons of poisonous industrial lead residues that have accumulated in cities during the past century,” Patterson wrote in a National Academy of Sciences report. Sure enough, according to Lanphear’s study, despite the striking drop in blood lead levels over the last 50 years, these amounts are still “ten times to 100 times higher than people living in the preindustrial era.”

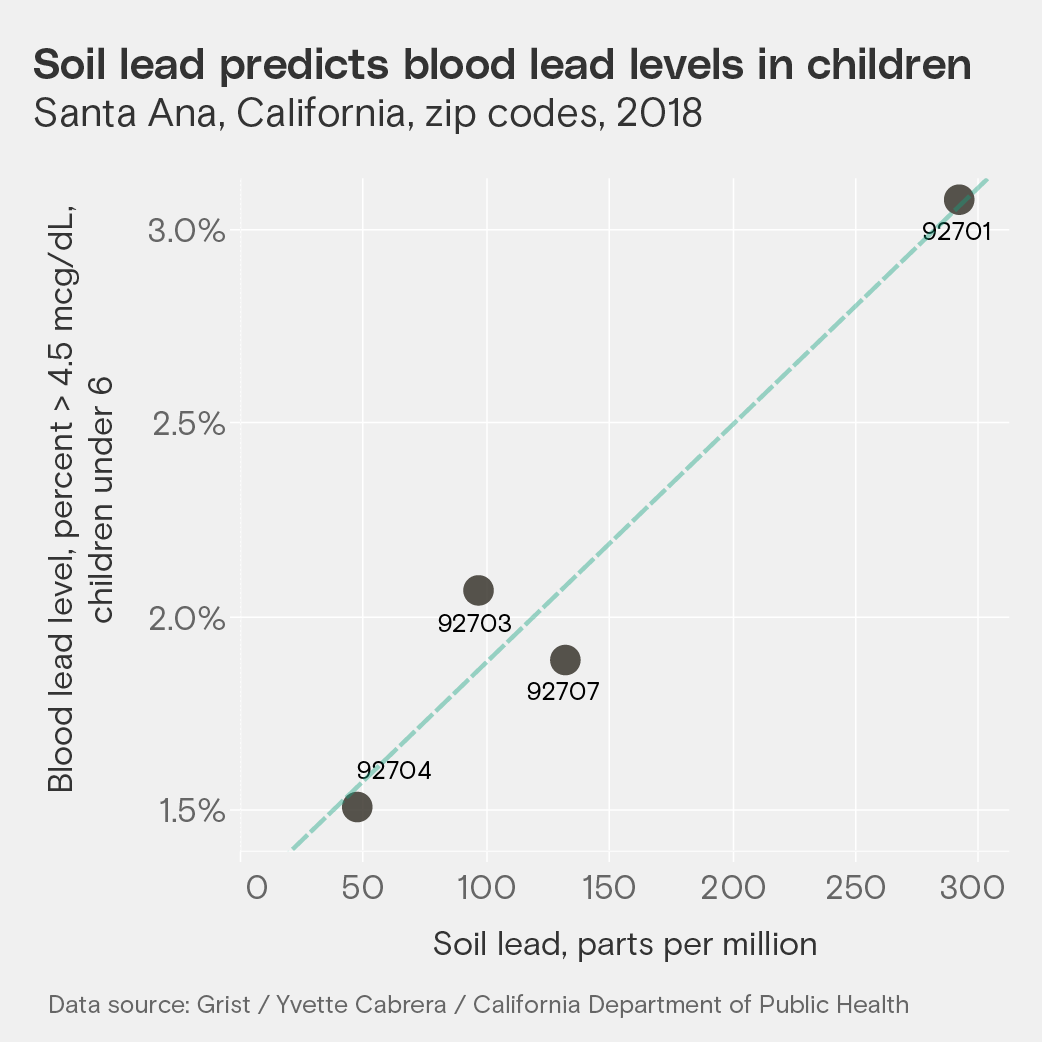

Comprehensive, citywide soil lead mapping in urban centers has been limited, for the most part, to the realm of university researchers in a small number of cities. Nobody had mapped Santa Ana until six years ago, when I went door to door in the city’s predominantly immigrant and low-income neighborhoods with an X-ray fluorescence analyzer, which produces X-rays to measure the lead content of soil. I found lead in nearly a quarter of more than 1,000 soil tests. In addition, I discovered that the ratio of Santa Ana children who had dangerous levels of lead in their blood exceeded the state average by 64 percent. Latino children represent the majority of children who are lead-poisoned statewide, according to public health data.

To follow up on that investigation, in 2018 and 2019 I conducted more than 600 soil lead tests in residential areas of the city that were zoned for industry or are adjacent to industrial areas. Fifty-five percent of those tests, which were conducted on residential properties and public spaces, showed lead concentrations that exceeded the level that the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment considers dangerous for children: 80 parts per million. Nearly 9 percent of those tests showed lead concentrations higher than 400 parts per million, the federal standard set in 2000 by the Environmental Protection Agency as hazardous for children in residential play areas. (It should be noted that, in 2012, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said that lead is not safe at any level in children’s bodies.)

The combined soil lead tests clearly point to where the greatest concentration of hazardous lead soil contamination is found in this 27-square mile city of 335,000 people: in neighborhoods like Logan, French Park, and Lacy, which are situated in the historic urban core of the city. Many of these neighborhoods are low-income, densely populated, and predominantly Latino — as is all of Santa Ana, a majority-Latino city (nearly 78 percent) that skews young, with about 27 percent of the population under the age of 18.

In response to my first investigation, a coalition of residents, advocates, and academic scholars has spent four years raising community awareness about the dangers of lead exposure in the city. In 2020, the coalition released a study that corroborates my findings, highlighting how children in Santa Ana’s poorest areas are at a higher risk of being exposed to lead soil contamination. The study, led by a team of researchers at the University of California, Irvine, analyzed more than 1,500 soil samples collected throughout the city and found a higher incidence of lead contamination in the city’s poorest neighborhoods and areas with the highest percentages of young children, residents without health insurance, and renters.

Although regulations like the national ban on lead in gasoline and the phase-out of lead paint have significantly reduced lead in the environment — and with it, levels in Americans’ blood — the legacy contamination has not been addressed comprehensively, leaving large deposits of lead in neighborhoods with a history of high-density traffic flow and industry, according to one of the nation’s top experts on soil lead contamination, Howard Mielke of Tulane University’s School of Medicine. At the federal level, existing laws primarily focus on regulating the present and future production, use, and disposal of chemicals, but they don’t offer solutions to intervene in already-contaminated areas unless polluted sites are large-scale.

“We’ve reached a point where [children’s blood lead levels have] come down enormously, but not evenly for the whole community,” said Mielke. “There are still the communities that are in the interior of the city where the highest traffic flows were in the past, or lead industry, incinerators, a combination of lead aerosols — all cleaned up, but it’s still in the environment and it’s still exposing children at unacceptably high levels.”

One of the challenges, according to Mielke, is that while much work has been done to decrease water contamination and reduce air toxics, soil is typically ignored as a potential source of contamination. While the U.S. has a national Clean Water Act and a Clean Air Act, there’s no federal Clean Soil Act to address soil contamination comprehensively. Further, at the local level, not enough is done by public health care agencies to proactively pinpoint hot spots of soil lead contamination by using existing childhood blood lead level data, Mielke said.

“Unfortunately, public health has been in denial,” said Mielke. “They don’t seem to connect the dots. If you put something in the air, ultimately it will contaminate the ground.”

“In some ways, what we are experiencing is uninhabitable cities,” he added. “It’s very tragic.”

The soil lead contamination in Santa Ana is not unique. Soil lead mapping conducted by researchers across the country and around the globe shows that soil contamination is pervasive and widespread. A recently published study found that lead particles deposited in London’s soil by leaded gasoline throughout the 20th century continue to pose a threat to Londoners as contaminated dust is recirculated in the air near highly trafficked streets. In the U.S., Mielke and others have mapped soil lead levels in small and large urban centers like Baltimore, New Orleans, Minneapolis, Chicago, Detroit, and Pittsburgh, noting the same trend — that, as in Santa Ana, there are higher levels in the interior cores.

Further, racial and class disparities among children with elevated blood levels have persisted since the height of leaded gasoline use in the mid-20th century, with higher numbers of Black, Latino, and low-income children suffering from elevated levels. Harvard University sociologist Robert Sampson has shown that, while the risk of lead exposure is higher in poor neighborhoods, it’s even higher in racially and ethnically segregated neighborhoods. In a 2018 article in the Annual Review of Sociology, Sampson and his colleagues examined blood lead level differences across small neighborhoods in Chicago. Even when controlling for factors such as poverty, housing, and population density, they found that Black neighborhoods still had higher levels of lead exposure.

Sampson also discovered that even within these neighborhoods there was variation in the blood lead levels, which he attributes to the local manufacturing history. He found that lead exposure rates are higher in neighborhoods that have mixed industrial and residential uses, much like Logan.

“You have this phenomenon where you have residential units smack up against, like a battery shop, a paint [shop], or an industrial shop. Some people are kind of shocked actually at that, but it was not unusual,” Sampson said. “It’s still not unusual.”

Like his mother, Chepa, Joe Andrade was raised in Logan. As a young adult, he moved away for more than a decade but ultimately returned to settle on Logan Street, where he’s now raising his grandchildren and running the neighborhood association in a no-nonsense style: no fees, no bureaucracy, just a determination to protect the barrio.

“If we have something to fight for, we get together and we take care of business,” he told me.

Landmarks may be lost over time, and memories can fade, but for people like Andrade, whose family history is intertwined with protecting the barrio, the battle scars remain. The few, dedicated families of Logan who persisted are a story of a people who paid the cost of modernization while being segregated from the very progress that Santa Ana hoped to achieve.

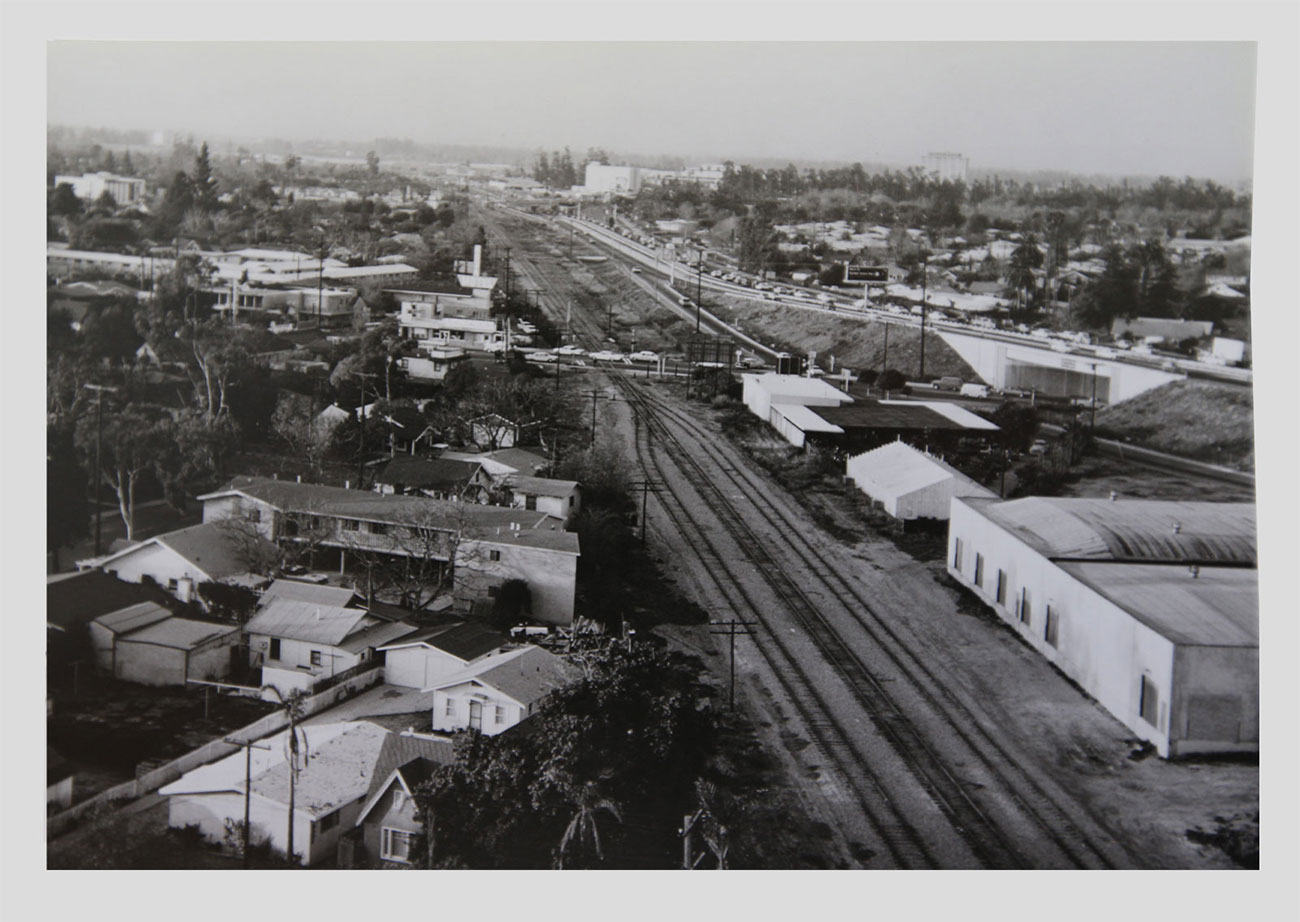

In the late 19th century, Logan attracted the Mexican and Mexican American railroad workers who helped build the Santa Fe and Southern Pacific railroads. The Southern Pacific — the first railroad to Santa Ana — was completed in 1877, nine years before the city was incorporated. Before the turn of the century, the Santa Ana Chamber of Commerce was outlining its vision of the city as the urban center of the region — a vision that became reality over the next century. Local publications described Santa Ana as a “sitting queen in the midst of this smiling valley of happy homes and fruitful lands.”

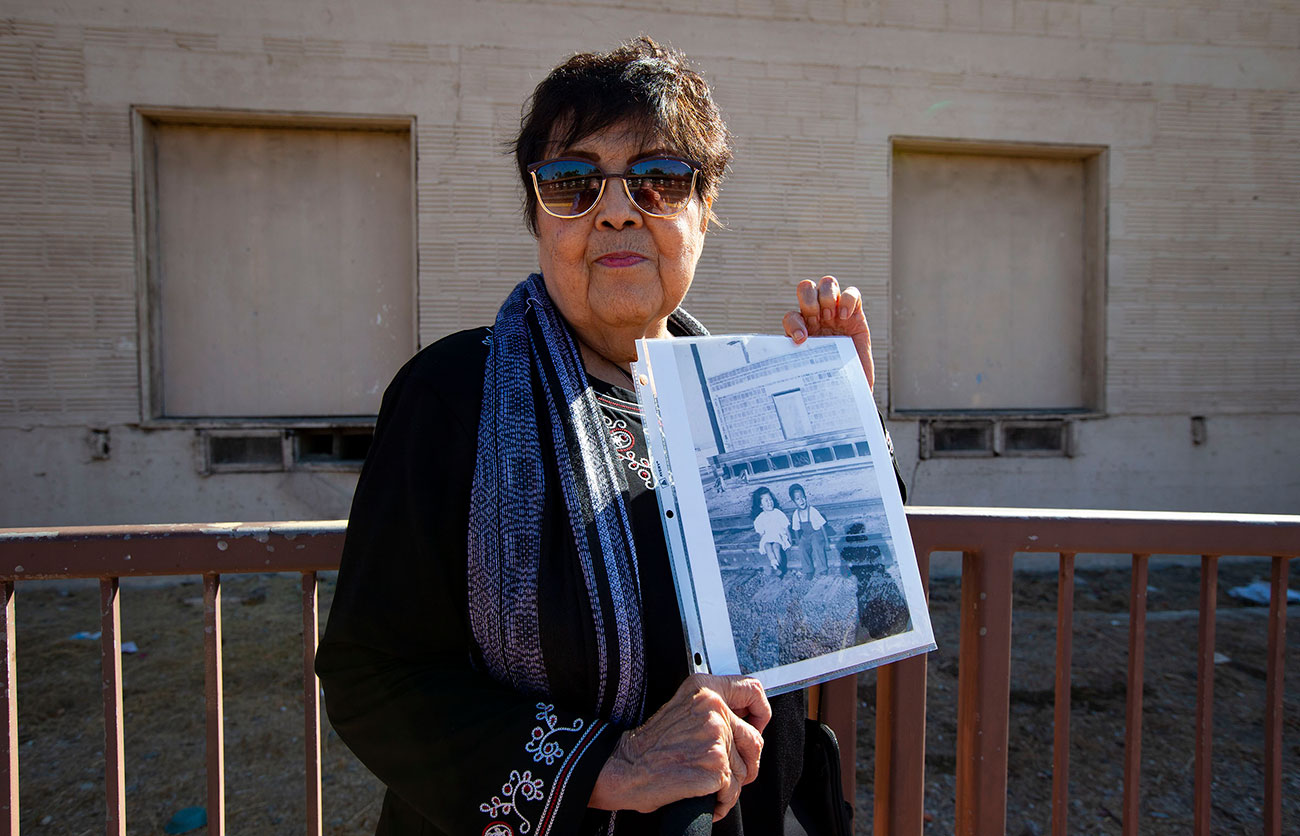

Though Logan, an agricultural area, was originally settled by European Americans, the residential neighborhood “became Mexican because it was one of the very few places that Mexicans could actually live and buy,” said Mary Acosta Rodriguez Martinez Garcia, who compiled the history of her neighborhood into a book, Santa Ana’s Logan Barrio: Its History, Stories, and Families.

“We had everything here that we needed,” said Garcia, whose mother, a seamstress, worked seasonally packing oranges and walnuts from the area’s agricultural groves. The scent of oranges trailed her in the summer, followed by the fragrance of walnuts in winter. The natural alchemy of the neighborhood was hard to duplicate, and it’s why children who grew up in Logan often returned. They couldn’t find that chemistry elsewhere.

The east side of the town became a distribution hub for agricultural goods and a burgeoning manufacturing center, with working-class neighborhoods built along the railroad tracks. During the first decade of the 20th century, according to historian and anthropologist Lisbeth Haas, Santa Ana’s Mexican Americans — California-born Mexicans or Mexicans who had migrated to the U.S. before 1870 — settled exclusively in those multi-ethnic neighborhoods, including Logan, which were zoned for residential use in an early city ordinance. By 1910, 40 percent of Logan’s households had Spanish surnames.

“The important thing about the barrios is they became very specific sites of commerce and culture and family life, and are really thought of as a really positive space in those days,” said Haas, a history professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Nevertheless, the barrios were essentially abandoned in terms of urban development, she noted. Many didn’t have sewers until the 1960s and lacked other basic amenities.

Historical documents from that era show that racially restrictive covenants in residential deeds prevented Mexicans, Blacks, Asians, or “any person or persons not of the Caucasian Race” from occupying, leasing, or renting homes in neighborhoods north and immediately northwest of downtown Santa Ana, which were distanced from the industrial zones. At Grist’s request, Orange County archivists searched for and found evidence of half a dozen such covenants in Santa Ana. One from 1941 restricted “African, Mongolian, Japanese, Asiatic, Spanish, Mexican, or Indian races or their decendants [sic]” from occupying lands and properties in a tract called Westwood Park. The earliest racial covenant uncovered was part of a grant deed signed in 1921, while the latest was signed in 1943, just five years before the U.S. Supreme Court ruled such covenants unenforceable.

Santa Ana planning commission records show that the commissioners were strategically approving and denying zone changes that placed a heavier industrial burden on eastside barrios that were near the downtown central core. In 1929, records show that the commission was pressured by the Santa Fe Railroad and Richfield Oil companies to consider zoning a portion of the Logan barrio for heavy industrial use.

This moment could be seen as Logan residents’ first fight against city officials, as planning commission minutes indicate that residents opposed this zoning change, and the commissioners backed off and denied the zoning request in June of that year. The win was short-lived, however: A month later, the planning commission did an about-face and voted unanimously to rezone the entire Logan barrio to heavy industry. In other parts of the city, by contrast, the planning commission showed an unwillingness to place industry within residential neighborhoods, denying permits to operations like welding shops and protecting other neighborhoods of single-family homes from being rezoned to allow for oil drilling.

By the end of World War II, Santa Ana had more than 50 industries and only two industrial areas. The boundaries of the two zones fell squarely around existing Mexican barrios in the city, including Logan. As the city pushed to attract more industry in the following decades, the commission’s zoning decisions would have dramatic long-term consequences for the Latino residents in those neighborhoods.

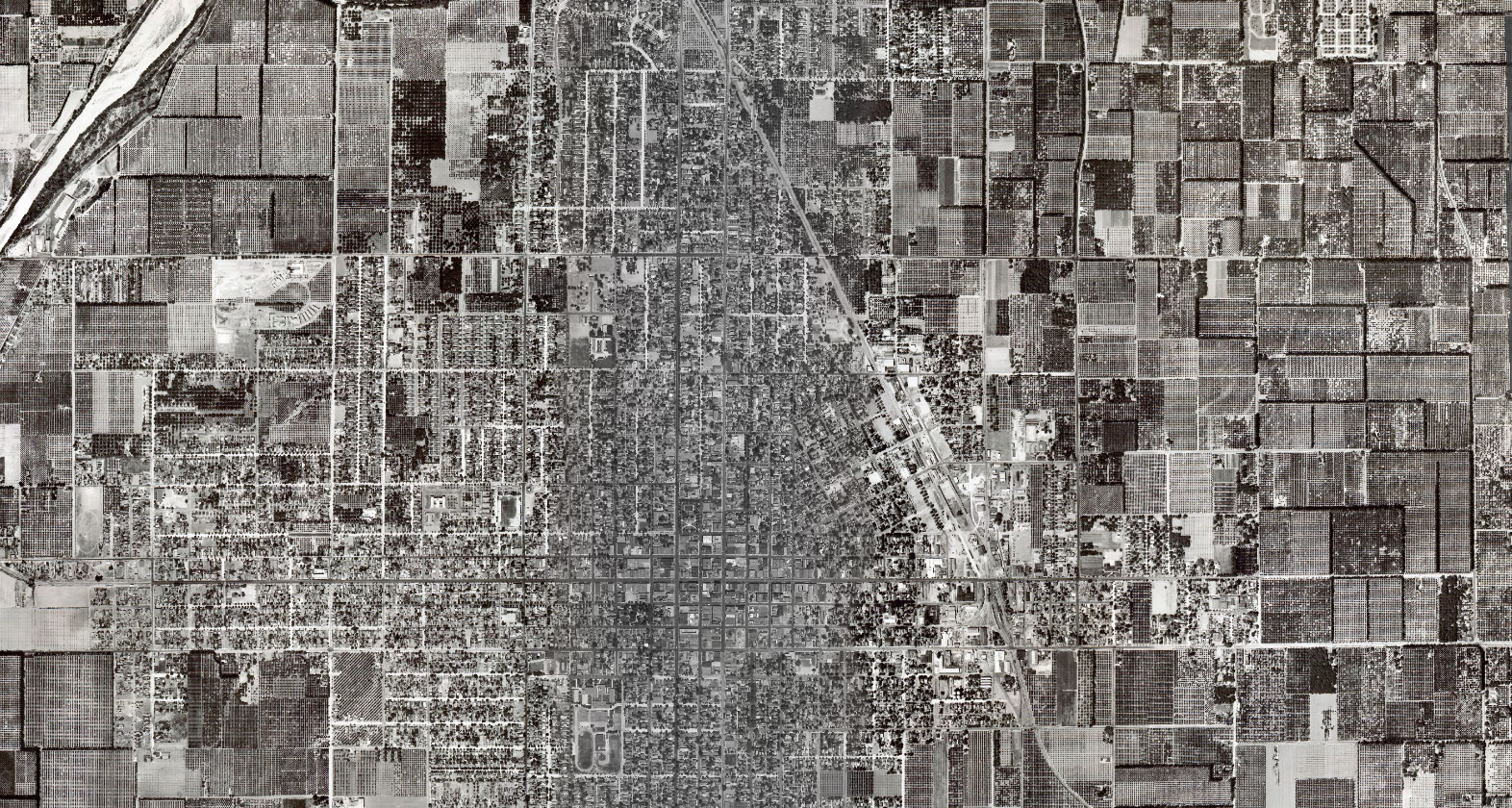

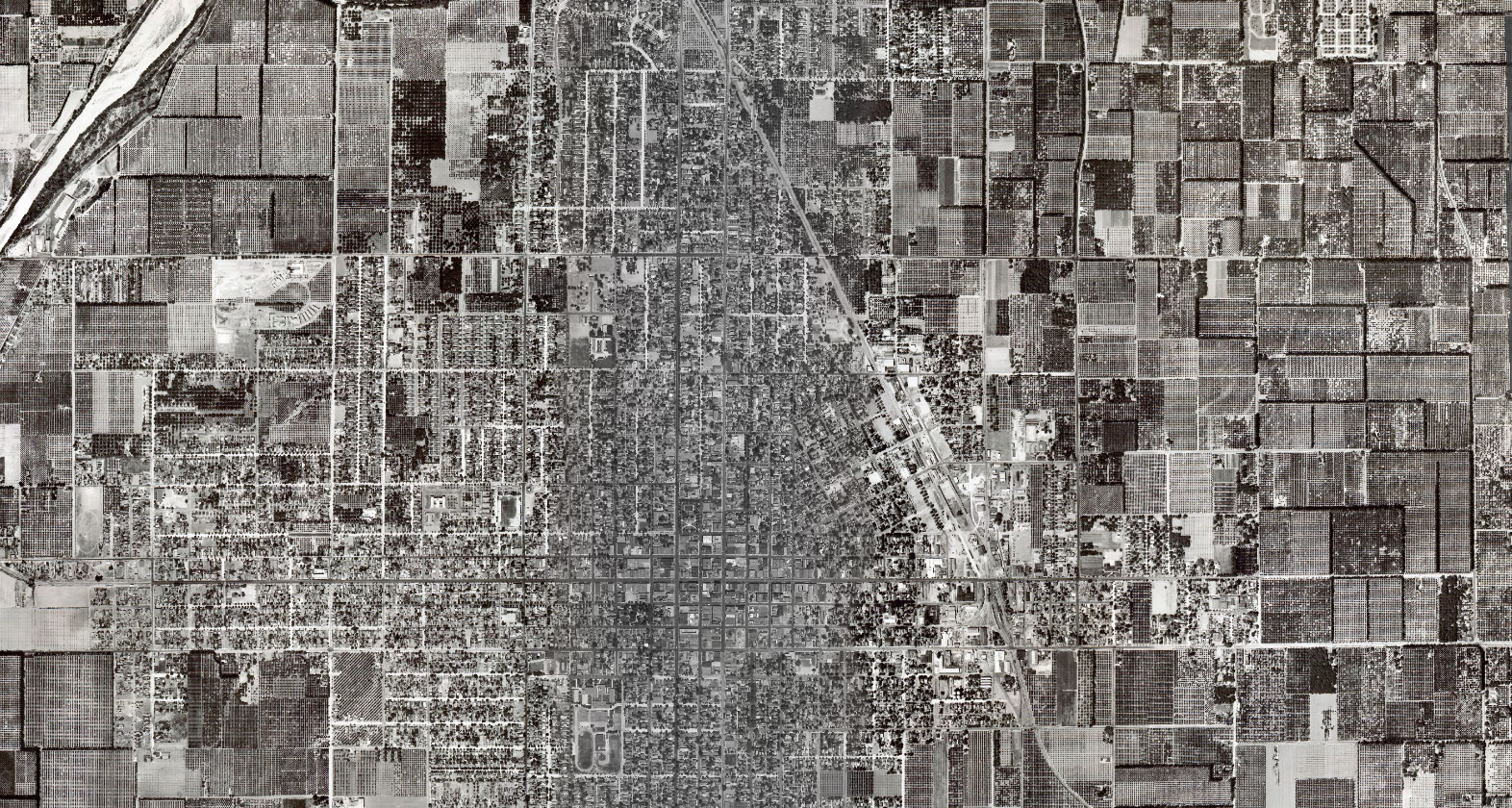

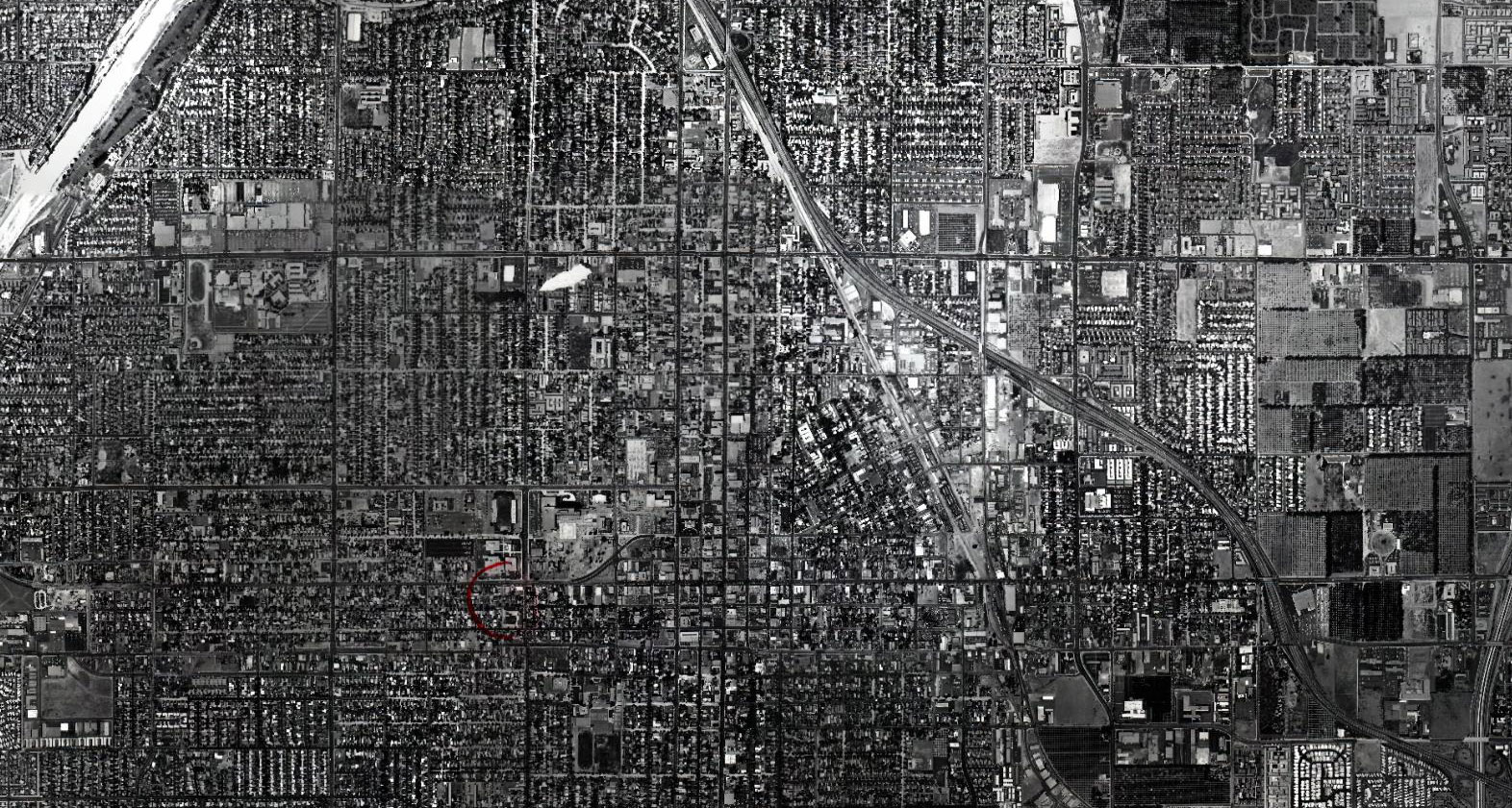

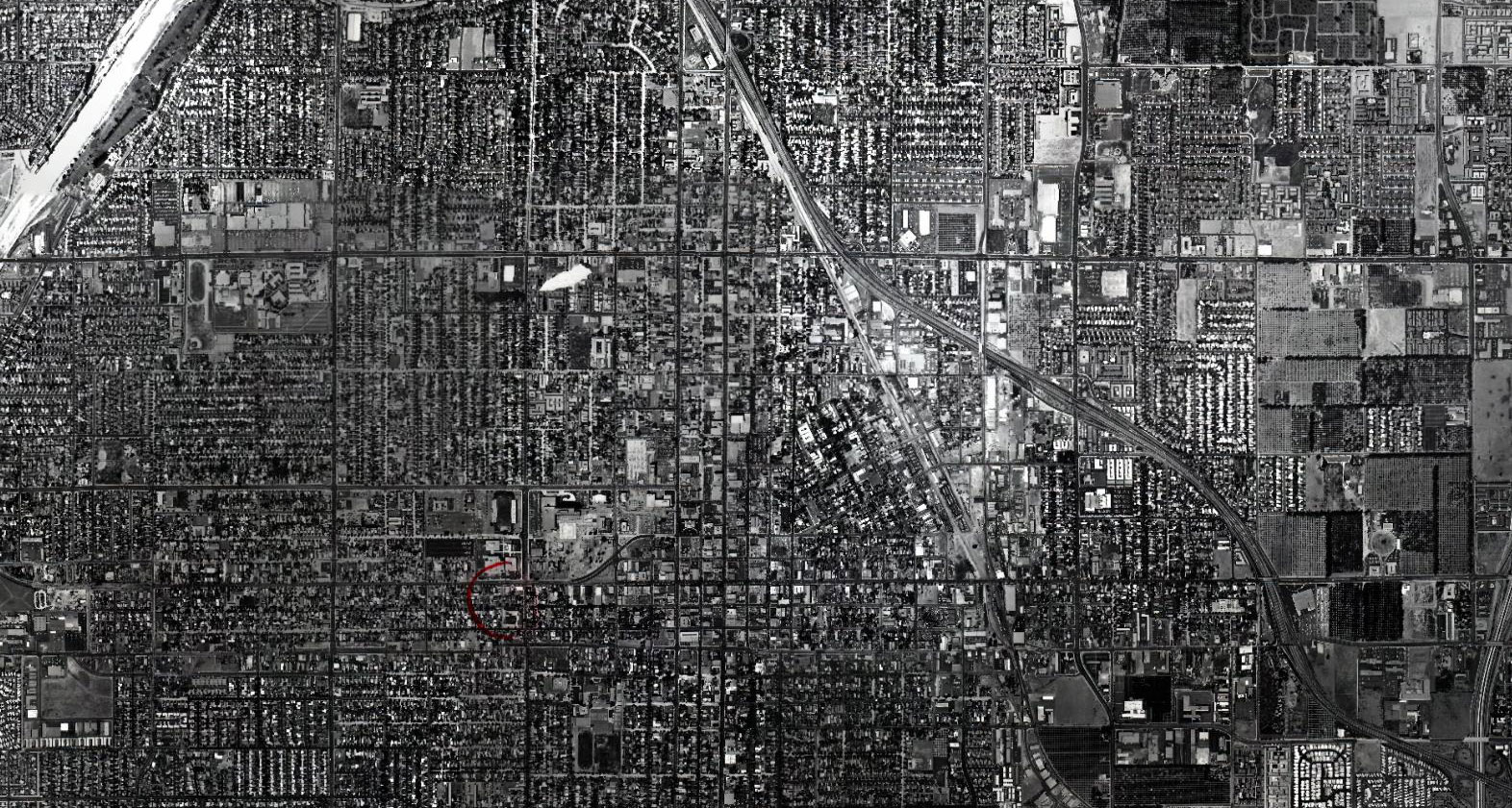

1931

1931

1947

1947

1953

1953

1960

1960

1970

1970

1980

1980

1990

1990

In 1953, as the expansion of the industrial pockets took root, the city announced an amendment to the zoning ordinance prohibiting the construction of new dwelling units or major additions to dwellings in industrial zones like Logan. Even after a 1969 zoning amendment permitting improvements and expansions on existing homes, few residents applied for such permits, conducting little rehabilitation on their homes and not building new homes for more than a quarter of a century.

In a 1982 oral history interview conducted as part of a project with California State University, Fullerton, Chepa Andrade described how the residents were caught off guard when the city first zoned the neighborhood as industrial in 1929. Many residents only learned about the decision when a sign was posted in the neighborhood, she said. When the 1953 prohibition preventing residents from improving their homes took effect, the condition of the barrio’s housing spiraled downward. “The city has been trying to get rid of the neighborhood,” Chepa said. “They’ve been trying to get rid of us for years and years.”

As homes fell into disrepair, the city condemned them. “A lot of the folks around there, once their houses were condemned, they had no alternative — so they had to move,” said Romero. His father was one of the few residents fortunate enough to be able to renovate his home without a loan after he became the first Latino to get a job paving roads with the city’s public works department, a job that paid him a higher wage than most of his neighbors.

Shortly after the city implemented the zoning amendment, the Logan barrio and the neighborhoods surrounding it were struggling. Data from the 1960 U.S. Census show that the eastside of Santa Ana was further entrenched in poverty. That year, the census tract encompassing Logan had the highest percentage of Mexican-born people in the city: Nearly one-third of its population had a Spanish surname. The residents had a median education level of seven years and a median family income of $4,993. The census also found that nearly half of the population with Spanish surnames occupied housing that was either deteriorated or dilapidated.

That year, construction of the Santa Ana Freeway was completed. The highway not only reshaped the physical landscape of the region — some Logan families had already been displaced to make way for freeway construction — but also introduced new industries as well as toxic traffic emissions during the height of leaded gasoline use in automobiles throughout the U.S.

A 1963 visual survey conducted by the city noted a change in character in the central city area, where neighborhoods were deteriorating, where people of color lived, and where buildings were old and poorly maintained. For example, an industrial corridor just south of the Artesia barrio is described as a “no-man’s land of industry, yards and green houses,” while another industrial and heavy commercial strip in Northwest Santa Ana is described as “unattractively developed” in a large “Mexican area.” The city described the housing in Logan as poor and noted the neighborhood’s open storage yards and deteriorating buildings.

In 1969, the city lifted the ban against home improvements and expansions, but residents told city officials that they still faced resistance from banks who weren’t eager to make loans in a neighborhood that was still zoned industrial. By the early 1970s, the barrio had over 130 single-family and apartment units as well as more than 30 industrial or commercial properties, including metal works, auto salvage shops, and lumber supply businesses. One resident, whose property shrank when the state appropriated a portion through eminent domain for the construction of the Interstate 5 freeway, told the Los Angeles Times that her house rattled when the trains passed, and she didn’t like how the nearby junkyard burned tar on Saturdays.

By 1970, about 8 percent of the acreage in the area around Logan was dedicated for manufacturing industries. At the time, the vast majority of the land was zoned for either light or heavy industrial use, while only 1.4 percent was zoned residential. The industrial businesses at that time employed between 1,200 and 1,400 people, but few of those firms employed Logan residents. A 1970 housing condition survey found that many homes had fallen into disrepair, with only six units in sound condition; only 10 percent of the dwellings were worth more than $10,000.

City documents from that era showcase citizen concerns that Santa Ana’s eastside residential neighborhoods were bearing the brunt of the city’s industrialization, describing these areas as having the “highest degree of inter-mixing” of single-family homes with commercial and industrial uses. In 1972, the Santa Ana Human Relations Commission submitted a resolution noting how grievously the Logan community had suffered at the hands of past planning commissioners due to zoning decisions and the introduction of industry to the barrio.

Those fateful decisions would lead to an explosive level of turnover of polluting businesses in Logan in the latter half of the 20th century. A Grist analysis of businesses that churned through Logan from the early 1960s to 2014 shows that a majority of those businesses no longer exist, and have been replaced by new commercial or light industrial businesses. The problem, according to Brown University’s Frickel, is that even as environmental regulations were put in place at the local and national level during the late 1980s to monitor polluting industries, this business-by-business approach cannot account for pollution and contamination left behind by businesses that have closed up shop.

“Our laws regulate individual pieces of property and adjudicate those claims on a case-by-case basis, so it’s the wrong scale,” said Frickel.

Despite the challenges of living in an industrialized neighborhood, Logan residents tended to put down roots, settling in the barrio for long periods — the mean length of residency at the time was nearly 20 years — “indicating a high degree of community stability,” the 1970 housing survey found. The cohesiveness of the neighborhood was hard to duplicate, and it’s why children who grew up in Logan, like Joe Andrade, often returned.

In the early 1970s, Logan residents began organizing. They realized that the city intended to split the neighborhood in half by extending Civic Center Drive East through the heart of the barrio. Sam Romero said the proposed road extension opened residents’ eyes to just how little regard the city had for the neighborhood.

Logan residents would defeat the Civic Center Drive plan, forcing the city to reroute the thoroughfare around the barrio. That kicked off a period of organizing against zoning and land use planning decisions to further defend the barrio from industrial encroachment.

In 1976, as part of a redevelopment project to “revitalize” Santa Ana’s downtown area, city planners recommended that Logan be incorporated into a project to construct an industrial park. A consultant also proposed phasing out residences in Logan altogether. The irony was not lost on Chepa, who told the Los Angeles Times that when she was a child, the barrios were the only place where Mexicans could live: “Now they’re saying we can move out of here, can live anywhere we want. But we can’t, not with the (housing) prices the way they are. Where can we go?”

Latino community activists from across the city came together and were trained by professional organizers from the Oakland Training Institute, an organization founded by Jesuit priests. Eight neighborhoods, including Logan, joined together by 1977 to create the Santa Ana Neighborhood Organization, or SANO. In her book Postsuburban California: The Transformation of Orange County since World War II, Lisbeth Haas described the tactics that the Logan barrio used to protest the revitalization plan as a crucial part of a grassroots movement that redefined municipal politics and brought the struggle for civil rights straight to city hall. The residents called on local leaders to address the political and economic implications of urban development for the city’s Latino working class. “For the first time, a Latino neighborhood defined itself to the public and press, making its history and the organization of community life the grounds on which the neighborhood should be saved,” Haas wrote.

Romero, who was part of the negotiating team representing Logan during discussions with the city, said residents sprang into action, attending city council meetings, protesting, and pressuring city leaders. Even his mother, who at the time was about 70, went before the city council to declare: “If you move me, I will die.”

By 1977, when the barrio had 130 residential units and 20 industries, residents were calling on the city to phase out those businesses by removing the neighborhood’s industrial zoning designation altogether. The city resisted. The councilman who represented Logan told the Santa Ana Register that the zoning change was not the answer, claiming that if it happened, many residents wouldn’t be able to afford to upgrade their homes, or would choose not to upgrade. Meanwhile, Chepa rallied Logan residents by “banging on doors.” She was able to fill the city council chambers.

In 1979, after two years of debate, organizing, protests, pamphlet-waving, marches, and meetings, the Santa Ana City Council approved a plan to rezone portions of Logan from industrial to residential. At the time, Romero praised the decision, noting in a Los Angeles Times article that the plan would ease the way for families to seek low-interest loans to upgrade their homes. The existing industrial businesses would be allowed to remain, but the new ordinance also established a residential zone — a striking victory that the Los Angeles Times noted was an about-face that had occurred only once before in modern Orange County history.

“We’re not going back to sleep like we did the other times,” Romero, then the newly-elected vice president of the SANO coalition, told the Times. “And the city knows it.”

As the Logan residents began to reclaim parts of their barrio, city documents indicate that Santa Ana’s leaders knew about potential soil lead contamination that had stemmed from the neighborhood’s multiple industries, as well as leaded gasoline emissions from the Interstate 5 freeway. A 1978 environmental assessment done as part of a general plan amendment to rezone Logan outlines how the neighborhood was located in a part of town where lead concentrations were consistently high. The report noted that, in order to avoid carbon monoxide and lead pollution near the freeway, “it would be helpful to perform field tests to determine the fall-off of concentrations of these contaminants with distance.”

In response to a request from Grist, the city of Santa Ana searched for but could not locate any records indicating that these field tests were conducted in response to the 1978 report’s recommendation. That report also said that, at the time, airborne lead concentrations were declining and would continue to do so as lead was phased out of gasoline. However, if Logan was converted to residential use, the report cautioned, more people would likely suffer from lead exposure.

And that’s exactly what happened.

The 1980s saw a construction boom of high-density apartment complexes on Santa Ana’s east side, which increased the population in the very areas that had long borne the brunt of industrialization — and where Grist’s own testing found elevated levels of lead in the soil. In essence, by allowing private developers to replace single-family homes with high-density apartment complexes, the city effectively increased the number of children exposed to lead and other contaminants. One survey of a Logan ZIP code by the nonprofit Latino Health Access in 1996 showed that, on average, about half the residents there were younger than 20.

Nevertheless, long-time neighborhood dwellers continued to fight with city officials to preserve the residential qualities of their neighborhood. As late as 1987, the city’s planning manager predicted that Logan would someday be “completely industrial.” By that point, the neighborhood was about evenly split between residential and industrial zoning, according to Deputy City Manager Rex Swanson. He told the Orange County Register that Logan had all the markings of an industrial area: “The only thing that has made it a neighborhood is that people have lived there and wanted to stay.”

And they continued to want to live away from polluting businesses. In 1994, residents rose up to oppose a car salvage yard that had proposed opening near the Interstate 5 freeway. The last thing residents wanted was more noise and more traffic, they argued at the time. Ultimately, the salvage yard withdrew its request.

The next year, Romero was again in front of the city council advocating for a residential-only designation for the neighborhood. In an Orange County Register story, some council members were quoted as saying they “didn’t think they’d ever find a final solution to a problem that began before they were born.” They also pledged to try to be fair to both sides. Ultimately, the neighborhood would remain mixed-use — though Romero and Joe Andrade have worked with the city to convert various individual industrial parcels back to residential use.

“The idea has always been that we’ll try to revert Logan back to purely residential,” Romero told me.

The mixed-use nature of the Logan neighborhood has burdened residents with exposure to pollution, health problems, and a bevy of annoyances. So in addition to working to make Logan more residential, local activists must also battle to ensure that nuisance businesses comply with existing regulations. The city may have heard their calls to change the “business-as-usual” approach in recent decades, but ultimately, those who live there now still pay the price for the decades that it was an industrial hotspot.

Even in recent decades, as science has provided more evidence to justify transitioning polluting industries out of the neighborhood to protect human health, the residents have yet to convince the city to help right a wrong that scarred the barrio so long ago. “We tell the city, ‘What you guys did, the bad things you did to the neighborhood — all we’re asking is that you go back and put the neighborhood the way it was when we were kids,’” said Romero.

The contamination hollows out the victories, of course, but Logan remains a tight-knit community its residents are proud to call home. After years of hearing it from the barrio, Chepa Andrade explained in her oral history interview, the city appeared to learn a lesson: to leave the neighborhood alone. “They don’t dare come and touch us anymore,” she said. “We’re too united.”

That unity is apparent at Logan’s annual reunions, where residents proudly display photographs of the bygone years, dance to everything from doo-wop to Mexican ballads, and share plates of carne asada and lasagna.

In September, Romero arrived at Chepa’s Park carrying an armload of pan dulce. Glancing over the group gathered on the lawn, he tells me that with every year that passes “somebody is missing” from the reunion. He makes light of it, greeting a longtime pal with a sly, “You’re still alive!”

“So are you!” his friend retorts.

“Barely!” Romero answers with a chuckle.

The assembled kicked off the reunion by reciting the United States Pledge of Allegiance. Andrade stood up with his fellow residents, put his hand on his heart, and recited the words he’s known nearly his entire life in reverence of the only country he’s ever known: “one nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.”

For Logan residents, justice and equality have been elusive. Activating the neighborhood turned out to be the easy part. Going back in time to the era when orange blossoms and walnut orchards perfumed the air, when parents and children could breathe freely — that’s a challenge for tomorrow, for another generation, said Romero. “Hopefully,” he said, “in time this neighborhood will be back the way it was before.”

Romero, who is struggling with health issues, realizes his activist days are nearing their end. It’s time, he said, to pass the baton on to the next generation — though what keeps him up at night is wondering who exactly will take over for him and Andrade.

He’s not quite done yet, though, having just secured the recent concessions from the city to improve Logan’s infrastructure. It’s another victory that’s taught him never to give up. “We’re persistent. We raise hell,” said Romero, noting that he’s currently petitioning the city for new park playground equipment. “We’re getting results. They’re slow in coming, but they’re coming.”

Andrade has an idea who might take over for him and Romero, having recently brought in his adult son, Michael, to help organize. The younger Andrade is now working to make his father’s top priority a reality: ensuring that the neighborhood transitions back to 100 percent residential use. The barrio’s hope is that the city will establish a building fund to help rebuild the neighborhood by replacing industrial businesses with new homes.

Any effort to rebuild the Logan that once was would require cleaning up any contaminants found in the soil. In September, as part of an emergency resolution on climate change, the Santa Ana City Council pledged to address lead contamination throughout the city. Whether that includes remediating lead-contaminated soil remains to be seen.

Ultimately, if the transformation of Logan can improve the health of residents, Logan will have won, said Andrade, who has watched generations of Logan residents get cancers and battle heart disease and other health issues. His mother Chepa, who died of a heart attack while undergoing dialysis, was one of them.

Looking ahead, Andrade sees the future of his neighborhood with an eye toward the environment in which his grandsons, Nicholas, age 3, and Logan, 2, will grow up. On the day of the reunion, Nicholas scampered around Andrade, trailing his grandfather as he finished last-minute arrangements. Standing under a weeping willow tree, the child scooped up a handful of rocks and dirt and began sorting the rocks. Within minutes, he had dirt streaks on his face and hands. “I’ve got some rocks to paint,” he happily declared.

Naturally, lead contamination concerns Andrade. Despite how much he and his wife clean their house, there’s an ever-present layer of dust that seeps in from outdoors. “How can you [protect your children]?” he asked. “You can’t keep them in the house all the time.”

The Logan that Andrade sees today is not the Logan that he or his sister, Cecelia Andrade Rodriguez, remember from childhood. Andrade Rodriguez, now 71, lives nearby in the city of Garden Grove but still helps organize the annual Logan reunion. She dreams of one day returning to her old neighborhood for good. But she understands the risks of the contaminated environment. At 42, she was diagnosed with breast cancer, which her doctor told her was likely due to environmental causes.

In the 1970s, when her mother, Chepa, was fighting the city’s efforts to extend Civic Center Drive through the middle of Logan, Andrade Rodriguez said she was too young to understand the ramifications. But today, Andrade Rodriguez realizes how crucial her mother’s, her brother’s, and the barrio’s battles were to protecting Logan from further environmental degradation. Her hope is that she’ll make it back to Logan before she dies. “I do want to come back to Logan,” she told me. “Or I want to come as close as I can to Logan.”

But as long as the toxic dust remains in the earth, and as long as the Santa Ana winds whip through the streets of Logan, Andrade Rodriguez realizes that the only way to return to the cherished barrio of her youth is by letting her imagination carry her to a place that once was.

Read more about Grist’s soil testing methodology

Over two years in 2018 and 2019, Grist tested more than 600 soil samples across three Santa Ana zip codes to measure for the presence of lead. Ninety-five percent of the tests were conducted in the field with an X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analyzer, and 5 percent of the soil samples were sent to the Tulane University School of Medicine for laboratory and XRF analysis.

A representative from Massachusetts-based scientific instrument company Thermo Fisher Scientific trained Grist’s reporter, Yvette Cabrera, to operate an XL2 600 Niton XRF analyzer, which produces X-rays to measure the lead content of soil. The company loaned the XRF analyzer to Cabrera and calibrated the analyzer for soil testing.

The soil samples were collected in public spaces such as sidewalks and parks, community gardens, and residential yards with verbal consent from the occupant. The testing was conducted on bare soil throughout residential yards with a focus on areas where children would be likely to play. Grist also tested soil along the perimeter of yards near fences, as well as the areas near the outer walls of a housing structure.

The 601 soil samples tested with the XRF analyzer in the field had an average margin of error of 18 parts per million. Grist discarded any soil tests with incomplete scans, which could be caused by any disruptions that produced a movement of the XRF analyzer during analysis.

A small batch of soil samples were sent to the Tulane University School of Medicine laboratory of Dr. Howard Mielke, one of the nation’s leading experts on soil lead contamination, to confirm the accuracy of the XRF tests in the field. His lab conducted an agreement analysis and found that Grist’s soil samples and Tulane’s analysis had a very strong agreement of nearly 90 percent. “Essentially the two measurements are the same,” said Mielke.

The XRF tests measure the amount of lead in the soil, but they do not determine the source of the lead.

To create the Santa Ana soil map in this story, Grist combined the 2018-2019 Santa Ana soil tests with a series of tests conducted by Cabrera as part of a 2017 lead contamination investigation for ThinkProgress. For that investigation, Cabrera conducted more than 1,000 soil tests throughout Santa Ana in the fall of 2015 and spring 2016. The tests were done primarily in residential yards, but some were also conducted in parks, along bicycle trails, and near sidewalks. Those soil maps can be found here.

Clayton Aldern contributed data reporting to this story.

Original photography for this project was done by Daniel A. Anderson. Jacky Myint handled design and development. Teresa Chin and Mignon Khargie supervised art direction. Amelia Bates provided illustration.

This project was edited by John Thomason, Nikhil Swaminathan, and Kat Bagley. It was copy edited by Kate Yoder and Matt Craft. Angely Mercado handled fact checking. Myrka Moreno, Jacob Banas, and Sarah Pineda did additional promotion and production.

This story was produced in partnership with the McGraw Center for Business Journalism at the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at the City University of New York. This report was also made possible in part by the Fund for Environmental Journalism of the Society of Environmental Journalists, and by the Kozik Challenge Grants funded by the National Press Foundation and the National Press Club Journalism Institute.

A special thank you to Orange County Archivist Susan Berumen, Assistant Archivist Chris Jepsen, and Digital Archives Specialist Steve Ofteli, as well as the staff of the Santa Ana Public Library History Room, Vermont Law School’s Cornell Library, and the Sherman Library & Gardens in Corona del Mar for their expertise and assistance in archival research. The Josephine Andrade oral history interview is provided courtesy of the Lawrence De Graaf Center for Oral and Public History at California State University, Fullerton. The soil testing was made possible thanks to the generosity of Thermo Fisher Scientific, which provided an XRF analyzer on loan to conduct soil testing for this investigation. Aerial photographs of Santa Ana are courtesy Orange County Public Works.

Cover photographs:

- Mary Garcia’s cousins sit on railroad tracks in the Logan barrio in this vintage photo from her childhood in the 1950s. Courtesy of Mary Garcia

- Students from Logan Elementary, a segregated school, play football in the school yard in this photo from the 1940s. Photograph courtesy Mary Garcia

- Logan neighborhood association president, Joe Andrade, helps his grandson, Nicholas, on the front porch of his longtime Santa Ana home. Photograph: Grist / Daniel A. Anderson

- A 1964 aerial view of the train tracks and the Santa Ana freeway in the Greater Logan area. Photograph courtesy of First American Title Insurance Company

- Many years of drought have intensified dusty conditions in Southern California, exacerbating the dangers of lead particle inhalation from contaminated soil. On their daily walks to and from school, Santa Ana children risk exposure. Photograph: Grist / Daniel A. Anderson