This post originally appeared on the Great Energy Challenge blog, in partnership with National Geographic and Planet Forward.

John Maynard Keynes, a giant in modern economic theory, famously wrote, “Most, probably, of our decisions to do something positive, the full consequences of which will be drawn out over many days to come, can only be taken as the result of animal spirits.”

This notion, laid out in his seminal book, The General Theory of Employment Interest and Money, was meant to push back on the notion that people behave in an purely economically rational manner, that many of our decisions are based not solely on a cool weighting of probable costs and benefits, but also on “spontaneous optimism” to act.

So professionally, we’ve known at least since Keynes wrote this in 1936 that sentiment and gut instincts drive a lot of our decisions. Score one for common sense.

Practically, what this means is that if people feel bad about their economic prospects, that “spontaneous optimism” is likely to be absent. This is why, for example, many of us think the Recovery Act was so critical. Cutting taxes can be a good way to get people to stimulate the economy: lower the cost of creating jobs, and businesses are more likely to create them.

But the decision to invest in a new factory doesn’t just depend on the cost of the investment, which lowering taxes can help reduce, but also on how much it’s expected to return. And when our animal spirits drive our expectations into the ground, cutting taxes is almost useless. If someone thinks there’s not going to be any market for widgets and that economic disaster might be right around the corner, then even completely eliminating the taxes on labor to make widgets or on the profits from selling them won’t be enough to get someone to build a widget factory.

A few weeks ago, I wrote about a report from Deutsche Bank that, among other things, outlined what they thought markets would need to see for clean energy investments to take off. Basically, they boiled it down to TLC: Transparancy, Longevity, and Certainty.

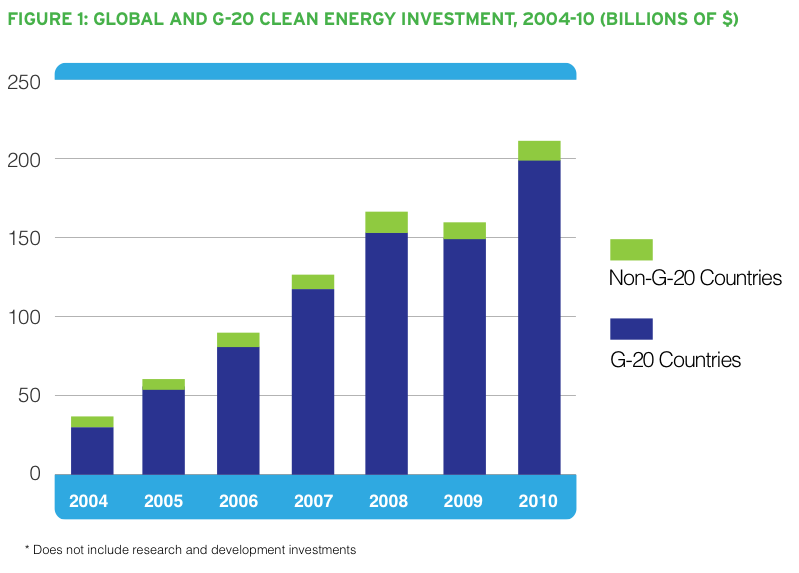

Last week, the Pew Charitible Trusts showed what happens when markets don’t see those things. Their report, “Who’s Winning the Clean Energy Race,” had some great news. In 2010, over $240 billion was invested in cleantech worldwide. That’s an increase of about 30 percent from 2009 levels. About $198 billion of that was in G20 nations (the 20 largest economies), an increase of 33 percent over 2009.

This is great news, of course, because it says something about the state of our global animal spirits. Coming off a terrible economic year in 2009, this shows that business sentiment is improving in clean energy industries and probably overall as well. No one is going to invest in new energy capacity if they think economies are going to continue their free fall. And significant amounts of those energy investments are going to clean alternatives.

The bad news, of course, is what’s happening in the U.S. After slipping from first place to second place in 2009, we fell again from second to third last year. 2010 was a decent year for clean energy investments in the U.S.: our $34 billion of investment was a 50 percent increase. And while it seems unlikely that we’ll fall to fourth behind Italy next year, there’s also very little chance that we’ll overtake either Germany or China to regain second.

The problem goes back to the absence of TLC in our clean energy policy. The Pew report highlights policies like renewable energy standards and feed-in tariffs as important drivers of clean energy investment. It shouldn’t be surprising that China is setting aggressive long-term targets for itself and that Germany pioneered the idea of feed-in tariffs which help guarantee economic returns to clean energy investments over the long haul.

How about the U.S.? We’re actually going backwards. Last year was a pretty good one, but a lot of that was driven by recovery spending, which is running out. Congress is looking for way to cut support for renewable energy and efficiency programs. The only predictable policy signal Congress seems willing to send clean energy markets at the moment is that they can’t count on predictable policy signals from Congress. Faced with these policy prospects, other markets just look a lot more promising for clean energy investments.

Put all of this together, and 2011 is looking a lot more like 2009 than 2010 of the U.S. clean energy industry. While the rest of the world is getting dressed up for the clean energy party, it looks like the U.S. is going to stay home and wash its hair. In the clean energy world, countries like Germany and China are the real party animals, while the U.S. runs the risk of becoming increasingly confused and dispirited.