Kathy Lenniger was running her dogsled team one day along her usual route in Fairbanks, Alaska, when she suddenly splashed into overflow, fresh water spilling on top of the snow. Surprised and chilled, she returned to the parking lot, where a lanky man was loading a sled with science equipment. Nicholas Hasson, it turned out, was studying thawing permafrost — research that could shed light on the streams and sinkholes that recently materialized around Lenniger’s property and all around town.

Lenniger lives in a log cabin in Goldstream Valley, a spruce-lined swale with a rolling view of the Northern Lights near Fairbanks. “It’s the birthplace of American permafrost research, actually,” said Hasson, a Ph.D. student at the nearby University of Alaska Fairbanks, or UAF. During World War II, the military feared the ribbons of dancing light were interfering with its radar, so Congress passed an act in 1946 establishing the Geophysical Institute at UAF. Soon, scientists were investigating the strange phenomena in the sky and drilling boreholes around Goldstream Valley to study the frozen ground beneath their feet.

Since then, temperatures in Fairbanks have shifted so much that the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration officially changed the city’s subarctic designation in 2021, downgrading it to “warm summer continental.” As the climate warms, the ancient ice that used to cover an estimated 85 percent of Alaska is thawing. As it streams away, there are places where the ground is now collapsing. Many of the valley’s spruce trees lean drunkenly. Sometimes, only a thin layer of soil covers yawning craters where the ice has vanished, what Hasson calls “ghost ice wedges.” Its absence has already fundamentally changed how — and where — people can live.

Birch trees, left, bend as the ice below them melts near the University of Alaska, Fairbanks. Collapsing trees are one of the more visible signs of permafrost; as ice thaws, the ground can slump, moving enough to overwhelm trees with shallow root systems. Right, Caution tape surrounds a large sinkhole caused by melting permafrost. Photos by Sean McDermott / Grist.

When Lenniger built her cabin several decades ago, she didn’t expect she’d need to regularly jack up her foundation. But for the last several years, she said, “if I have some water on my counter now, it rolls in this direction. It’s like, ‘Oh yeah, it’s sinking again.’” At first, she tried to fill the sinkholes popping up around her property with bones from the meat she fed her sled dogs, but eventually the pits grew large enough to strand a backhoe. Despite living in perhaps the most-studied permafrost valley in the country, Lenniger didn’t know how much worse her troubles might get — until Hasson offered to help.

On a muggy afternoon last summer, Hasson prepared to try to find out why Lenniger’s cabin was sinking. He pulled on a backpacking frame he’d jury-rigged to receive very low-frequency radio waves from antennae in Hawaii, recording the modulations of the electric field to map the permafrost beneath the duff. The colors of the aurora come from the charged particles of solar wind, which collide with oxygen and nitrogen in the Earth’s ionosphere and create a glowing halo. The free electrons from these collisions can reflect radio waves, helping Hasson understand how permafrost is thawing below the surface. Combined with a $40,000 laser he dragged behind him on a plastic sled he’d nicknamed “The Coffin,” Hasson is able to link surface methane emissions to the ice disappearing underground.

As he scrambled off Lenniger’s driveway into the brush, Hasson explained, “It’s just like an MRI — we’re able to scan and see where water is flowing.” Walking across her yard, he found a new underground river had formed under a corner of Lenniger’s home, which explained why her land had caved in.

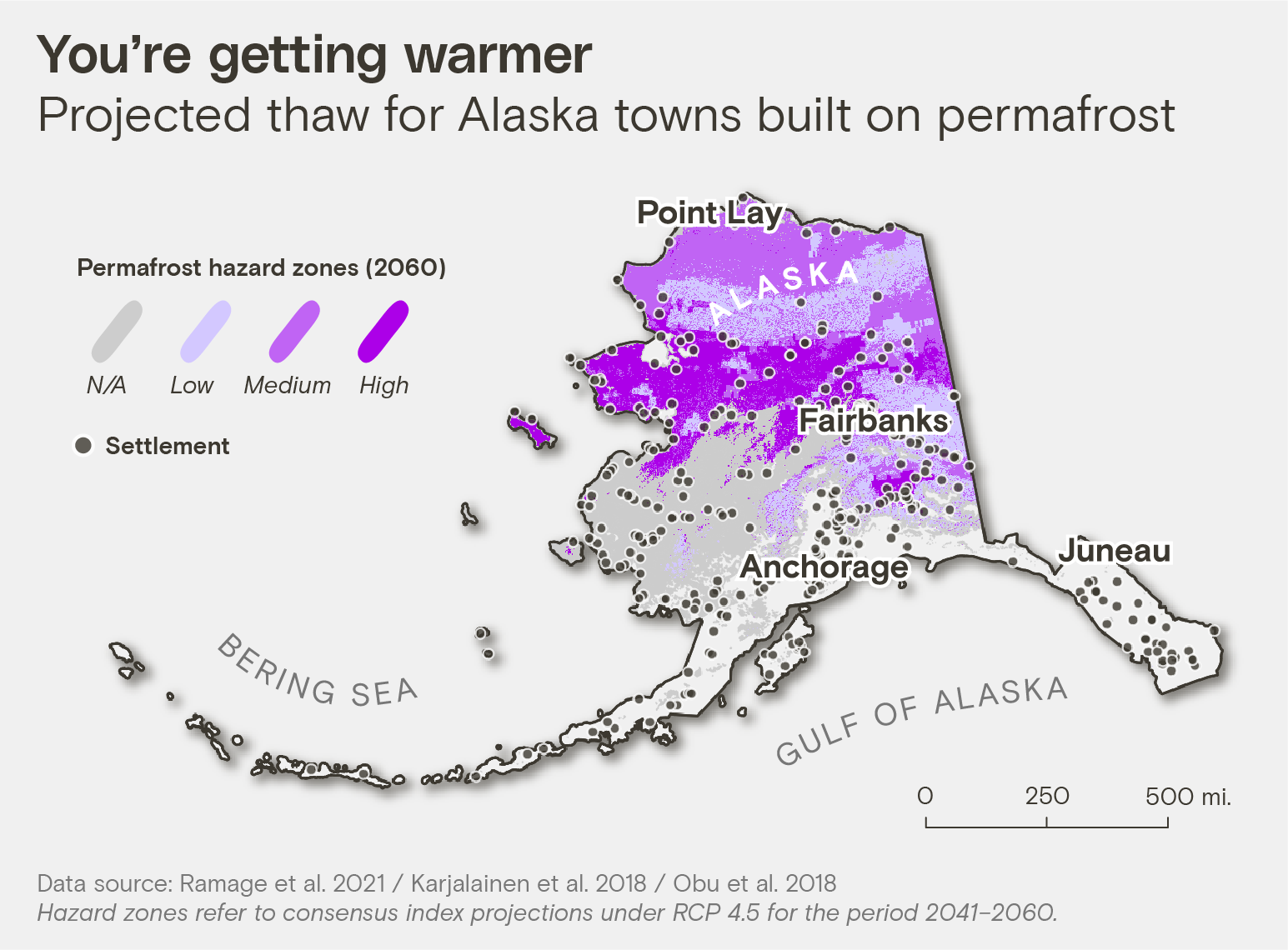

The permafrost around Fairbanks is discontinuous; jagged pieces of it finger north-facing slopes and enfold the low-lying valleys. Yet potential homebuyers who want to avoid it are left to guesswork. “There’s no comprehensive map of permafrost,” said Kellen Spillman, the director of the department of community planning for the Fairbanks North Star Borough. For those like Lenniger, whose properties later develop thaw-related problems, there’s little recourse, either from insurance or the government. The University of Alaska Fairbanks, home to much of the state’s permafrost research, has itself struggled with recurring sinkholes on its roads and parking lots. “We have invested funding to rebuild,” said Cameron Wohlford, director of design and construction at the school’s facilities, “only to have them fail.”

Homeowners around Alaska’s second-largest city are facing expensive repairs, or even having their properties condemned. Hasson eventually traced the river running beneath Lenniger’s property to her neighbor’s, where the owner, Judy Gottschalk, reported that her septic pipes had broken as the ground settled. “My well went out this winter, too,” she said. Not knowing where else the ghost ice lies, Gottschalk has been nervous about putting in a new septic system. The drilling and construction required to replace it would cost her as much as $45,000, more than she originally paid for her house. “Everyone I know is having problems with their housing,” Lenniger said.

As parts of Alaska set record high temperatures in December, Fairbanks closed out 2021 with a destructive ice storm, causing roofs to collapse. A warmer Arctic is also a wetter Arctic, accelerating the breakdown of permafrost, explained Tom Douglas, a senior scientist for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory, in Fairbanks. “For every centimeter of rain, we see about one centimeter of additional top-down thaw,” he said. On average, Fairbanks now sees about five more weeks of rain than it did in the 1970s.

“In my 47 years here, I’ve never seen these kinds of conditions before,” Lenniger said. She has a lot of practice finding creative ways to take on Alaska’s hurdles: Before phone lines went in, she and her partner used homing pigeons to communicate while mushing, though she said she was unfazed when the birds were devoured by owls. But now, the rapid changes are testing her ability to cope. “Every day, it’s like now what will happen?”

Just as the earth clings to its former shape, leaving a record of where ice used to be, the very language used to describe these changes is revealing. The word permafrost, after all, is simply an abbreviation of “permanently frozen ground.” Much of Alaska’s permafrost is tens to hundreds of thousands of years old, first frozen when Goldstream Valley was grazed by mammoths. Now, that sense of immutability is slipping. “It was thought to be permanent — that any changes happened on a scale of tens of thousands of years,” said Vladimir Romanovsky, a professor emeritus of geophysics at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and a leading permafrost researcher.

Many variables influence permafrost’s stability, like how cold it is, how deep it runs, and the quantity of soil moisture, or its “ice richness.” In some parts of Alaska, ice extends nearly a half-mile below the surface, while in others, it has formed the landscape itself, sprouting tundra-covered ice hills called pingos.

Since 1993, Romanovsky has been taking field data from stations around the state, recording their increasing temperatures. At all of the 350 stations, soil temperatures have warmed substantially, and thaw is inching down to deeper depths. On the North Slope, one of Alaska’s coldest ice-rich regions, “when we started it was about -8, and now it’s -4 degrees Celsius, so we’re already halfway to zero,” he said. Dramatic changes will increase once this melting point between frozen and liquid is hit. He predicts that within 40 years, the Slope will be “at a critical threshold in normal, undisturbed conditions.”

Off the North Slope, this tipping point will be reached sooner. Any time soil or vegetation is disturbed — as the Army Corps of Engineers discovered in 1942 while trying to build a highway to Alaska — permafrost has a tendency to disintegrate into truck-swallowing mud. It’s a similar story with roads built in recent decades. Jeff Currey, materials engineer for the northern region of Alaska’s Department of Transportation & Public Facilities, explains that as ice wedges degrade under the state’s highways and airports, the asphalt heaves and drops, creating a dangerous roller-coaster effect. Because Alaska has relatively few roads across its 665,000 square miles, the ones it has are critical connections.

“Warming temperatures are contributing to increasing maintenance and damage,” Currey said. “Anecdotally, we’re having to fix the same places more frequently, and more intensively.”

Mitigation measures can help, from the low-tech approach of using gravel to channel cold air against embankments to high-tech thermosiphons, tubes that channel warmth aboveground during the winter to help keep the soil frozen. But Alaska’s budget for maintenance is largely dictated by the state legislature, and Currey calls the annual $330 million allotted to the northern region in recent years “inadequate.” Currey explains the average road is typically built to last around 30 years, but that’s largely based on expected traffic, not whether the road will be thermally stable. An independent study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences estimated that, as a result of climate change, the state will have to spend billions more on maintaining and repairing public infrastructure by the end of the century. Despite budget shortfalls, Currey predicts that “maintenance efforts simply have to increase.” In many cases, “we’ll tolerate rougher and worse roads than we do now — that will just be the economic reality.”

Around Fairbanks, elevating buildings to keep their heat from leaking into permafrost or designing structures to be adjusted isn’t new. Re-leveling houses as a cheap way to adjust to moving ground is an Alaskan tradition. “My grandparents used to chase the corners on their cabin when it moved, like everybody,” said Aaron Cooke, an architect and researcher at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory’s Cold Climate Housing Research Center, who has worked on these issues in many communities around the state. But with climate change, the old engineering tricks that helped keep permafrost frozen aren’t sufficient. “The ground is changing, even if you do everything right.”

To understand the scale of the impact when it starts to melt, Cooke said, you have to understand that “to someone in the north, the natural state of the ground, the default status of Earth, is frozen. And thousands of years of culture are built on that knowledge.” While the impacts of permafrost thaw — subsidence, flooding, sinkholes, and landslides — mimic the devastation of natural disasters, the Federal Emergency Management Agency isn’t responsible for permafrost damage, and it’s difficult to get covered by homeowner’s insurance. “How fast does a disaster need to move for a department that handles disasters to address it?” Cooke asked.

Romanovsky predicts that within a decade, the destruction in most parts of Alaska will get worse. “I’m worrying about my house as well,” he said. But regions with continuous and ice-rich permafrost, like those in northwest Alaska, will see the worst damage. “It will be the major problem driving relocation,” he said, “but these changes need to be understood at high resolution — for each village, for each house, you need to know what to expect.”

Where the Chukchi Sea bites into the North American continent, ice loss has driven thousands of walruses to the beaches of Point Lay, in northwest Alaska within the Arctic Circle. The predominately Iñupiat community, home to around 300 people, is wrestling with the loss of ice, too: In 2016, the lake they relied on for drinking water disappeared overnight after the ice wedge it rested on eroded, forcing the town to pump water from a nearby river. This year, one of the town’s holding tanks failed, spilling almost a million gallons. “Apparently, permafrost was melting under us,” said Lupita Henry, the Native Village of Point Lay’s former tribal president. “There are cracks in homes, doors that can’t close, houses that are so angled they seem unlivable.”

Now 40 years old, Henry was a young girl when the town’s first underground sewer lines were put in; many of them have since broken as the ground settled. The borough government recently installed new electric poles, which are already starting to lean. Like in many rural Alaskan communities, there’s a shortage of housing, but Henry said the thawing permafrost makes it difficult to build or even get a loan for a new home. “Where do you get your insurance? Through which bank can you finance to even get your home fixed?” she asked. “When the ground is falling underneath you, what do you do?”

In 2018, the state recognized a new hazard: usteq, a word from the Alaska Native Yup’ik language that describes the catastrophic land collapse stemming from thawing permafrost, and the erosion and flooding it entails. As sea ice disappears, the coast has been battered by intensifying storm surges, speeding the breakdown of permafrost under the shore. Riverbanks are corroding from thaw, changing everything from the chemistry of the groundwater to its distribution and movement. Permafrost, Henry said, “is linked to everything — our homes, water sources, food sources, vegetation.”

Point Lay is now working with researchers on a Navigating the New Arctic project, funded by the National Science Foundation, to try to determine the best engineering for building on its ice-rich and unstable ground. It’s all complicated by the fact that the remote town can only be reached by plane or barge, making construction more difficult. Even before the pandemic, supplies were regularly delayed. “All of the problems overlap,” said Jana Peirce, the project’s coordinator. Point Lay can apply to FEMA’s Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities program for help in adapting to permafrost thaw; the federal agency is now proactively trying to intervene, because the cost of responding to emergencies is, on average, six times more expensive than mitigation. But to do so, Point Lay will need an up-to-date hazard mitigation plan, and to form a plan, they need to know where the ground ice is, and how it might melt. “While there is no question that planning is important for smart adaptation,” Peirce said, “for a small community already living in crisis, this is just another hurdle.”

In the 2019 Alaska Statewide Threat Assessment, which set out to summarize the risks permafrost presents, Point Lay is ranked as one of the top three communities under threat from permafrost thaw. Yet aid has been slow in coming. “You tell them you need a water source, that your land is melting underneath you — how many meetings do I have to have until I’m given funding?” Henry asked. In March 2022, Point Lay became the first town in Alaska to declare a climate emergency, acknowledging the threat to their existence.

Towns across Alaska are facing similar challenges: The statewide threat assessment found that 89 of Alaska’s 336 communities are threatened by permafrost degradation. “The main barriers to addressing these threats include the lack of site-specific data to inform the development of solutions, and the lack of funding to implement repairs and proactive solutions,” Max Neale, senior program manager for the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium, wrote in an email. “We have yet to see significant engagement from state and federal partners to improve the efficacy and equitability of programs for communities facing climate change and environmental threats.”

In 2020, the U.S. Government Accountability Office found that federal assistance for climate migration has been ad hoc, and that the federal government is nowhere near prepared for the scale of relocation required. Cooke says temperate parts of the world simply don’t seem to have registered the urgency of Arctic change. He’s spent over a decade racing to help relocate Alaskan towns like Shishmaref or Kivalina, which, despite being deemed in imminent danger back in 2003, have not yet completed their move. But when he attends climate change conferences, “it’s very jarring to hear people still talking in the future tense.”

For many Alaskans, the emergency is already here. “If we can get a good idea of how much permafrost we’re sitting on top of,” Henry said, slowly, “we can try to get the federal government to help us with mitigation, or decide if we have to relocate.” Although facing a crisis, people in Point Lay are used to the idea of building for an uncertain future. “Don’t put any pity on us,” Henry said. “We’re strong people who survived thousands of years — and we will continue surviving.”

The scale of the problem is daunting, but there’s surprisingly little agreement on how much dealing with a thawing Arctic will cost. Over a dozen experts interviewed for this article admitted they weren’t sure how many Americans live on permafrost; a recent paper published in Population and Environment suggested a ballpark of around 170,000 people. Nor can anyone agree how much ice is where, much less how it might thaw.

Nearly a third of Arctic research is based on data from just two field stations: Abisko, Sweden, and Toolik Lake, Alaska. And researchers usually collect data during the Arctic’s short summer field season, even though winter conditions may look very different, making conclusions less accurate. For instance, recent studies have found that emissions of carbon and methane released by thawing permafrost have been drastically underestimated. There are 1.6 trillion metric tons of carbon currently stored in permafrost — twice what’s now in the atmosphere. New projections suggest that the amount of greenhouse gas emissions from permafrost could equal those emitted from the rest of the United States by the end of the century.

“It’s clear that the models are not capturing all the key pieces,” said Anna Liljedahl, a climate scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center, who is based in Homer, Alaska.

Research attempting to settle these questions generally falls into one of two camps. There’s top-down, like Liljedahl’s work with the Permafrost Discovery Gateway, which uses high-resolution satellite imagery to record thaw slumps and surface water changes. Machine learning and supercomputers have helped Liljedahl closely map visible ice wedges, creating a more comprehensive view of the Arctic, but can only infer what’s under the surface through identifying types of soil or vegetation.

The second approach is bottom-up: Romanovsky’s boreholes, for instance, deliver very detailed measurements from specific places, but researchers have to extrapolate to draw larger conclusions. Yet all permafrost is not equal. Take a type of permafrost called yedoma: frozen, silty muck from the Pleistocene era that releases 10 times more greenhouse gases than other types of thawing ice. Additionally, research indicates yedoma-rich regions may be warming the most quickly. So knowing how much yedoma there is, and where, is critical.

Scientists like Hasson hope to advance a third approach using airborne imaging spectroscopy, essentially mounting a fancier version of the laser on his sled to planes, a more efficient research method. This technique can detect large methane emissions, and Hasson can then use very low radio frequencies to identify what’s happening below the surface, identifying methane hotspots and providing information on the scale that infrastructure planning requires.

“The question is, why aren’t we doing this method at scale?” Hasson said. “Why am I not in a plane right now flying over Alaska?” The Department of Energy considers permafrost thaw and its emissions a threat to national security, and is partly funding Hasson’s research, along with NASA and the National Science Foundation.

Much is at stake. Dmitry Streletskiy, a geographer at George Washington University, explained that long before ice begins to thaw, warming decreases permafrost’s ability to support structures. In the spring of 2020, the 800-mile Trans-Alaskan Pipeline reported its first instance of “slope creep,” as thawing permafrost jeopardized its structural integrity. That’s likely what happened in the Siberian city of Norilsk a few months later, where thawing ruptured a huge fuel reservoir, prompting a cataclysmic diesel spill that dyed the region’s rivers blood-red.

Streletskiy started his career focused on ecosystems, but realized that “unless you put monetary values to things, it doesn’t get much attention. His most recent study found that 70 percent of major Arctic infrastructure is in areas that permafrost thaw could put at risk of damage within the next 30 years, increasing maintenance costs by $15.5 billion dollars, as well as causing another $21.6 billion in damages. And those are the paper’s most conservative estimates.

While Russia likely has the lion’s share of the world’s population living on permafrost, alpine countries like France and Switzerland will also see mountain slopes start to lose their stability, resulting in hazardous landslides. A recent study published in Population and Environment found that 3.3 million people currently live in settlements where permafrost will degrade by 2050, forcing many to relocate.

“Those who live on permafrost have a pretty good understanding of what will happen in 20 years — they don’t need scientists to tell them,” Streletskiy said. “It’s the people who live in D.C. or Moscow who need to pay attention.”

Up the rippling highway from Lenniger’s cabin in Goldstream Valley, Sam Skidmore shoveled dirt away from a vault door at his gold mine, the entrance to the deepest permafrost tunnel in Alaska. He’d decided to break his rule against opening it when the temperature was above freezing so Hasson could take ice samples. Skidmore stumped down into the darkness, his headlamp gleaming off ice crystals as he passed a wooly mammoth skull poking out of the wall. As they continued deeper, gravel beds betrayed warning signs of past eras, when dramatic warming transformed the landscape. “We’re literally walking back in time,” Skidmore said.

They descended between alternating layers of gravel and silt, passing eons when interior Alaska was an endless grassland steppe and eras when a changing climate shaped the landscape into more familiar forests. “Where we are now [in time], Homo sapiens hadn’t entered America,” said Skidmore, who is preserving the tunnel for research. He poked at a particularly pebbled section, saying it would take “a horrendous amount of rainfall to take all the trees and silt away and make a new layer of gravel like this.”

Today, the Arctic is again confronting dramatic change: As the region’s permafrost continues to thaw, some areas of Alaska will sink and get wetter, while others may dry out and burn, transforming habitats. Other studies show that permafrost under the ocean itself is thawing, reshaping the seafloor, forming craters the size of city blocks and elevating new pingos. For humans and animals alike, responding will be a balancing act, said Dmitry Nicolsky, a research associate professor at the Geophysical Institute in Fairbanks. Hazards will combine to create cumulative effects: As wildfires increase, for instance, people are told to cut vegetation away from their houses. “But making a safety buffer in Fairbanks might also cause permafrost degradation,” Nicolsky said.

Almost above Skidmore and Hasson’s heads, on the other side of the tunnel’s glistening roof, was one of the countless lakes that dot Alaska’s interior. In January at 40 degrees below zero, Hasson can drill into its frozen surface and light the escaping methane plumes into towering columns of fire. The lake is also releasing mercury, a toxic metal that could now be accumulating in Alaska’s water sources, as well as radon gas. Other ponds may emit neither, highlighting the importance of identifying not only where greenhouse gases are likely to be released, but new sources of hazards for human health.

Even in attempting to tally these changes, researchers may underestimate nature’s complexity. Liljedahl explained that when ice-rich tundra degrades, it can slump and become a pond. As it fills with moss, a very effective insulator, the underlying permafrost sometimes recovers, eventually filling up the depression with a bonus layer of new organic soil. “Instead of losing, it’s gaining,” she said. “We can’t lock ourselves into the idea that it can only go in one direction.”

Emerging back into the light, Skidmore stared out over the hills, where pockets of birch marked where mining operations disturbed the permafrost a century ago, creating pools and altering the forest. The catastrophic flooding revealed within his tunnel will happen again, he mused. “It’s only a matter of time.”