The world of biofabrication, where the organisms, cells, and molecules of life form the basis of our built world, is a weird and wonderful place. There’s furniture made of fungi, inks manufactured by microbes, lab-grown bones, and 3D-printed tissue. There are home bioreactors full of protein-rich algae and clothes cultured from animal cells. It’s the kind of biological utopia once relegated to science fiction, but now, thanks to advances in biotechnology and genomics, it’s becoming a reality.

To fashion designer Suzanne Lee, it’s a revolution that’s a long time coming.

“Once you start to understand what (biofabrication) could mean for reducing natural resource use,” Lee says, “you just think, ‘Wow. Why would we not be using biology?’”

Lee is the chief creative officer at Modern Meadow, a Brooklyn-based startup that’s growing slaughter-free leather from living cow cells. She’s also the director of a biofabrication consultancy called Biocouture and the founder of Biofabricate, an annual gathering for scientists, technologists, artists, designers, and investors who want to bring biological materials into our everyday lives.

“It’s just the dawning of a whole new bioeconomy,” Lee says.

[grist-related-series]

For Lee, that new bioeconomy came to light back to 2002, when she had a “serendipitous” encounter with a biologist and engineer in an art gallery, who told her that it was possible to make textiles using microorganisms. At the time, Lee was doing research for her book Fashioning the Future: Tomorrow’s Wardrobe, about the futuristic and high-tech fashions that people would be wearing decades from now. Microbe fabric certainly sounded sci-fi, so she decided to look into the idea.

Before long, Lee had fallen down the biofabrication rabbit hole. She began conducting her own experiments growing clothes from the bacteria and yeast found in a kombucha starter culture. The process was simple — just put the microbes in a bath of green tea, feed them sugar, and then wait a few weeks while they digest that sugar into cellulose fibers. Here’s Lee discussing the project for CNN:

[protected-iframe id=”baf5ef2b7f9f659e02e28d9bd42374c4-5104299-15574887″ info=”https://i.cdn.turner.com/cnn/.element/apps/cvp/3.0/swf/cnn_416x234_embed.swf?context=embed&videoId=tech/2011/05/27/natpkg.ted.suzanne.lee.biocouture.cnn” width=”416″ height=”374″]

The home-grown jackets made headlines around the world and made Lee into a TED fellow, but the designer-turned-amateur scientist knew that the method would never scale up enough to compete with the cotton industry. So when the experiment was over, Lee began exploring other early-stage biofabrication efforts. She found so much going on — not only with bacteria and yeast, but also with fungi, algae, and even animal cells — that she decided it was time to bring the community together to figure out where this all was going.

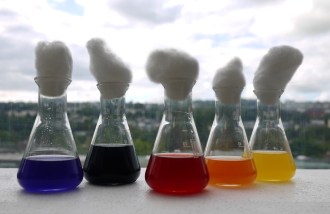

A startup called Pili Bio is engineering bacteria to make colorful pigments. The company emerged out of a biohackerspace in Paris, and its founders hope to replace the toxic, oil-based, and non-recyclable inks and dyes currently on the market.Courtesy of Biofabricate

“There’s a greater story to be told here, which is: What are these new tools? What are the new materials? What does this mean for the future of our everyday lives?,” she says. “And the people who tell those stories are the designers and companies who are thinking about reimagining materials and manufacturing.”

Last year, Lee brought those people and companies together for a one-day biofabrication bonanza in New York City. Biofabricate was smaller than a lot of other biotech conferences with about 250 attendees. The conference focused on the consumer applications of what might, in a different context, come off as somewhat dry and unapproachable science: genetic manipulation, cell culturing, materials engineering. The event also featured a design exhibition and a pop-up DIY biolab, courtesy of Genspace, New York City’s community biolab.

Designer Eric Klarenbeek 3D prints structures like this stool out of living fungi. His goal is to create products that have a negative carbon footprint. Courtesy of Biofabricate

“The power of an event like Biofabricate is that you bring together people in one room who wouldn’t ordinarily be networking with one another — scientists go to science conferences, designers tend to go to design conferences,” Lee says. “But this is a very unique day, where we put them all in one room and they all get blown away by what one another is doing.”

Last year’s conference focused heavily on how to grow structures from fungi. A company called Ecovative, which uses fungi to make compostable packaging material, even picked up a new client at the event, Lee says. And EpiBone, a company figuring out how to grow human bones in a bioreactor, scored a new investor, she says. The conference was such a success that Entrepreneur named it one of the top nine conferences worth attending in 2015.

This year, Lee and the rest of the Biofabricate team — fellow designers Amy Congdon, Annelie Koller, and Emma van der Leest — decided to keep the gathering small, after attendees from last year had requested that they maintain the intimate atmosphere. The sold-out event went down last month in the same cozy Times Square conference room.

Seattle-based startup Pembient is making 3D-printed rhino horns out of keratin powder — the same stuff that real rhino horns are made of. The team eventually plans to incorporate manufactured bits of DNA and other molecules found in real horns in order to make their product indistinguishable from what’s currently on the market. By providing a lab-grown alternative, the team hopes to reduce poaching.Courtesy of Biofabricate

The entire design exhibit at the conference was made out of recycled cardboard — an attempt by Lee to make the event waste-free.

“When you look at commercial exhibitions, they’re the last things on Earth that’s sustainable. There’s so much disposable rubbish, and I hate that. We have an anti-swag policy. If it’s not compostable, you can’t give it away at our event,” Lee says. “Even when people try to do it in a more eco-friendly way, and they give you some kind of organic cotton tote bag or whatever, they’re missing the point. The point is you don’t need it in the first place. It’s actually less about the material it’s made from than the throwaway culture that we’re trying to counter.”

So you won’t get a free bag at Biofabricate. You may not even get any paper. “We try and do everything digitally as much as possible,” says Lee.

These home bioreactors contain micro-algae that feed on ambient light, heat, and CO2 and grow into a nutrient-rich food source. Designers Jacob Douenias and Ethan Frier created the bioreactors, which are now on display at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Pittsburgh. Courtesy of Biofabricate

For Lee, one of the high points of this year’s conference was when Isha Datar of New Harvest, a nonprofit that supports research into sustainable animal products like lab-grown meat and leather, moderated a discussion between Oron Catts, an artist and researcher who has been playing around with lab-grown animal products since the ’90s, and Andres Forgas, the CEO of Modern Meadow.

“It was a kind of coming together, a conversation between someone who articulated this about 20 years ago with someone who founded the first company to be doing it for real today,” Lee says.

While Modern Meadow is still a few years away from having a commercial product, Lee already sees much more potential for lab-grown leather than the home-brewed cellulose she was making a few years ago. For one thing, leather is already a high-priced commodity item, she points out, so people will be willing to pay a premium for it. Plus, growing fabric from cells means you have much more control over the properties of the material than when harvesting it from animals.

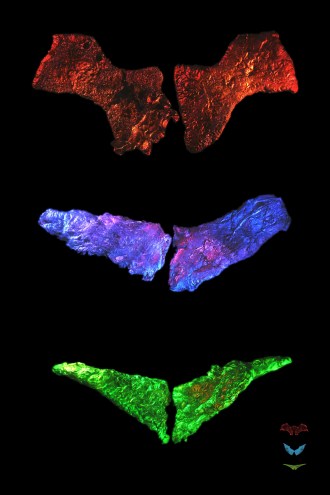

Artists Oron Catts and Ionat Zurr made these “pig wings” from lab-grown pig bone tissue. Their intent was to make people contemplate the future of lab-grown tissue transplants, both animal and human. Courtesy of Biofabricate

The company is also working on food products and already has an experimental “steak chip” that Lee describes as a cross between a potato chip and beef jerky. Like the leather, the meat is grown in a lab from a sample of living cells. Catts, Datar, and Forgas shared one of these steak chips on stage, Lee says, though the product is also a few years from market.

All in all, Lee says she thinks the public is ready for a biofabricated future, especially when it comes to fashion. People are becoming increasingly aware of the environmental costs of textile sourcing, the energy demands of manufacturing, and the poor treatment of garment factory workers, she says, and want to know that the industry is doing the best with the fewest resources. One company that Lee says is probably closer to market is the California-based Bolt Threads, which engineers yeast to replicate spider silk.

“The fashion industry really has woken up. There’s been so much bad press,” she says. “There are a lot of brands who are really trying to think about how they can do things differently.”

And if that means leather jackets — the iconic symbol of all things badass — will be coming from science labs, not slaughterhouses, then the sustainable revolution truly has begun.