To judge by recent Supreme Court decisions, the world didn’t know much about climate change a half century ago.

In 2007, when the court ruled that the Clean Air Act of 1970 gave the Environmental Protection Agency the flexibility to regulate carbon dioxide emissions, former Justice John Paul Stevens wrote, “When Congress enacted these provisions, the study of climate change was in its infancy.” Writing a dissent in a 2022 case looking at similar questions, Justice Elena Kagan argued that back in 1970 when Congress created the act, legislators gave the EPA the flexibility to keep up with the times, tackling problems (i.e., climate change) that couldn’t be anticipated.

Naomi Oreskes, a historian of science at Harvard University, saw those opinions as a sign of how little people understood about the past. “I remember just being mortified by that,” she said. To be sure, at the time of the first Earth Day in 1970, people were more worried about the immediate effects of smog than the long-term, climate-altering consequences of burning coal and oil. But Oreskes knew that scientists had been working to understand how carbon dioxide affected the global climate since the late 19th century. So she set about writing what she thought would be a short paper to correct the record.

In the process, Oreskes, along with other researchers at Harvard and Duke University, uncovered a lost history. As they searched troves of historical documents, they found plenty of other people were concerned about a warming planet, not just scientists, in the years before 1970. “We discovered a universe of discussions by scientists, by members of Congress, by members of the executive branch,” Oreskes said, “and the more we looked, the more we found.”

Her paper ballooned into an 124-page analysis, soon to be published in the journal Ecology Law Quarterly. And it’s only part one of the findings. Oreskes has found more than 100 examples of congressional hearings that examined CO2 and the greenhouse effect prior to the adoption of the Clean Air Act, evidence she plans to spell out in part two.

The research adds weight to arguments that Congress intended to give the EPA a broad authority to regulate pollution, including greenhouse gas emissions — a matter that has become more important, the authors say, in the aftermath of the West Virginia v. EPA decision in 2022 that limited the agency’s ability to regulate power plant emissions. The court’s conservative majority invoked a new argument called the “major questions doctrine,” requiring a very clear statement from Congress to authorize regulations that have “vast economic and political significance.”

Oreskes’ paper demonstrates that members of Congress, when discussing the Clean Air Act in 1970, were aware that addressing climate change could have significant economic consequences, for energy production and the automotive industry, for example. Oreskes hopes the paper will “put the lie to the myth that has been propagated that the Clean Air Act had nothing to do with carbon dioxide” and spur conversation among lawyers, judges, and legal scholars.

By the mid-1960s, climate change was already becoming a matter of concern to the federal government, the new analysis shows. A 1965 report from the National Science Foundation found that the ways humans were inadvertently changing the world — through urban development, agriculture, and fossil fuels — were “becoming of sufficient consequence to affect the weather and climate of large areas and ultimately the entire planet.”

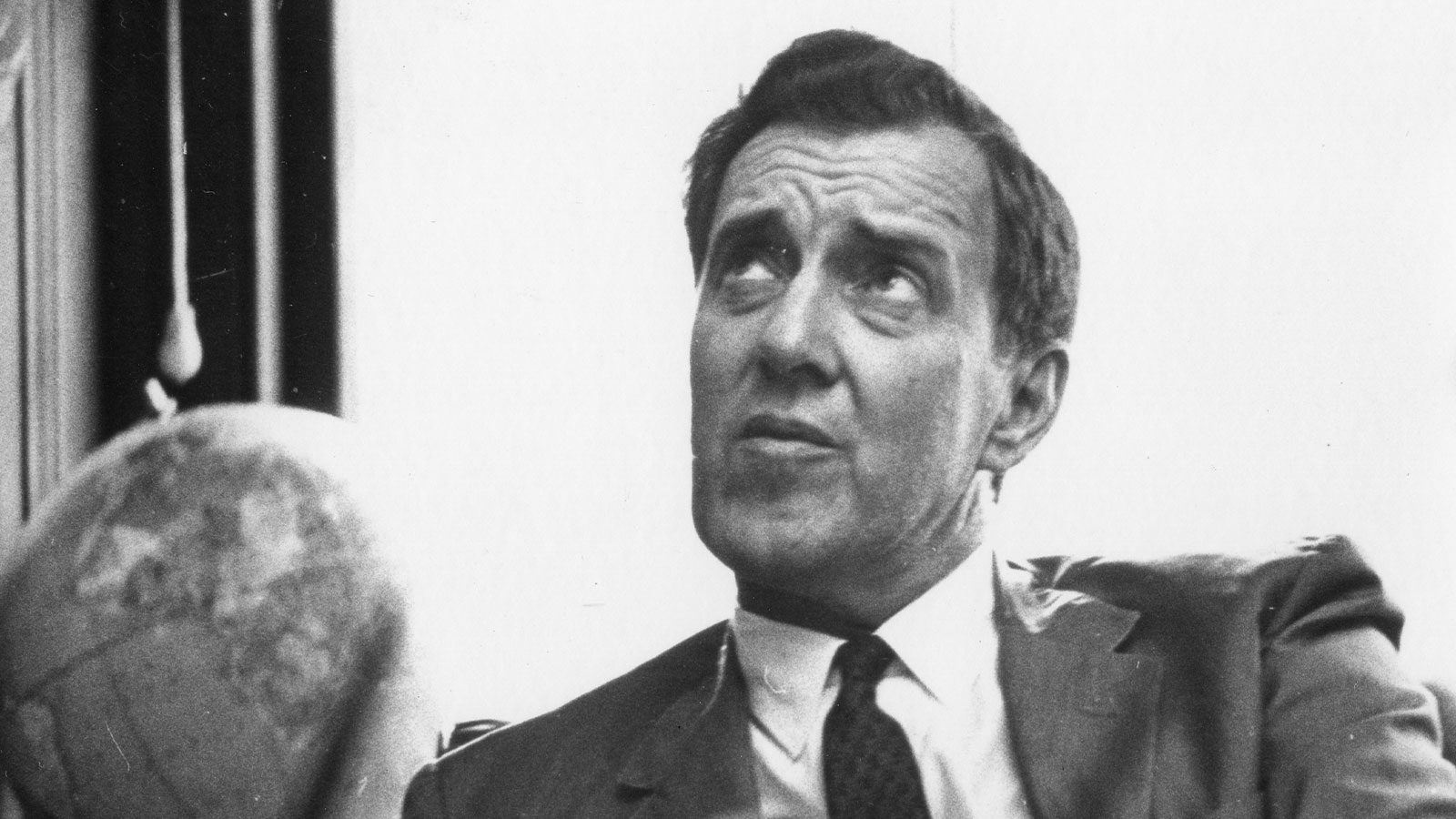

And the science was well-understood by many members of Congress, Oreskes and her colleagues discovered when they looked through the papers of Edmund Muskie, a Democratic senator from Maine who helped write the Clean Air Act, located at Bates College. The documents show that Muskie was deeply involved in conversations about climate change with scientists, and his staff tracked coverage of the topic closely in the press. In 1970, Muskie warned his fellow senators that if air pollution went unchecked, it would “threaten irreversible atmospheric and climatic changes.” (The Clean Air Act allows the EPA to regulate air pollutants that endanger public health, specifically including effects on weather and climate.)

Scientists generally recognized carbon dioxide as a pollutant in the 1960s, albeit a different kind of pollutant from the gases and particulate matter that were contributing to thick smog that dimmed cities in the middle of the day. By 1970, President Richard Nixon’s task force on air pollution proclaimed in a report that “the greatest consequences of air pollution for man’s continued life on earth are its effects on the earth’s climate.”

Oreskes and her team also unearthed documents from the National Air Pollution Control Administration — a federal agency established in 1968, later folded into the EPA — at a repository of federal records near Saint Louis. “Almost everyone has completely forgotten about NAPCA, if they ever even knew it existed,” Oreskes said. The head of the agency, John Middleton, testified in congressional hearings leading up to the Clean Air Act, discussing carbon dioxide and the potential economic impact of regulations, she said.

Ominous warnings of climate change had also reached the wider public. In 1958, Frank Capra, the famous filmmaker, produced an animated movie, The Unchained Goddess, that warned that just a few degrees of temperature rise could cause the seas to rise, so that tourists in glass-bottom boats would one day see “the drowned towers of Miami through 150 feet of tropical water.” It was shown to almost 5 million children in classrooms across the country. On The Merv Griffin Show in 1969, Americans were warned that a rapidly heating Earth could melt the polar ice caps. The next year, an article in Sports Illustrated, a magazine seemingly far-removed from environmental concerns, explained the science of climate change in detail, advising people “not to take 99-year leases on properties at present sea level.”

The Oreskes paper aims to provide the history and context that the court’s major questions doctrine seems to require. Despite this flood of historical evidence, Ann Carlson, an environmental law professor at UCLA, says she doubts the Supreme Court will take it into account. “I think if this court continues to display the hostility that it has displayed to environmental regulation, it can find ways to do so, whether or not there’s evidence that Congress understood that carbon dioxide was a pollutant under the Clean Air Act,” said Carlson, who previously directed fuel economy regulations for the Biden administration. The conservative justices have plenty of other lines of reasoning they could use to strike down regulations, she explained.

Oreskes acknowledges that it’s “an uphill battle with the present court,” but says that the paper will help strengthen the arguments of lawyers working to push forward climate cases.

Why has so much of this history been overlooked? Oreskes pointed to the “general historical amnesia of Americans.” As the politician Adlai Stevenson once put it, “The trouble with Americans is that they haven’t read the minutes of the previous meeting.” Even people working in environmental protection seem to have lost track of what happened, Oreskes said, perhaps because the EPA of the 1970s focused its limited attention on the acute pollutants that posed an immediate threat to public health — leaving the previous concern over CO2 tucked away in archives.