Hello, and welcome back to State of Emergency, a limited-run newsletter about how disasters are reshaping our politics. I’m Jake Bittle, a reporter for Grist, and I’ll be writing this newsletter along with my colleague, Zoya Teirstein.

It’s almost a truism that disasters offer an opportunity for positive change. That’s the idea behind President Joe Biden’s promise to “build back better” after the coronavirus pandemic, and it’s also the reason FEMA has poured billions of dollars into post-disaster adaptation projects. But in the five years I’ve spent covering climate disasters, I have almost never seen a place change for the better after a big flood or wildfire. Displaced victims scatter to hotels and rental apartments, developers and local lawmakers rush to rebuild everything the way it was, and no one gets any safer or more resilient even as the underlying risk increases.

The suburbs of Boulder, Colorado, which lost more than a thousand homes to the devastating 2021 Marshall Fire, are an exception to this rule. After the fire, a young council member named Kyle Brown leapt at the chance to fill a vacancy in the state Legislature, running on a promise to speed up the languishing rebuild. After taking office, he worked with survivors to draft and pass a suite of landmark bills that protect fire survivors and ensure future wildfires do less damage. In just one term, Brown has helped make Colorado a national leader on fire resilience.

As I reported this week, passing these bills required Brown to take on a host of powerful institutions at the state Capitol — insurance companies, banks, mortgage servicers, landlords, and even homeowners associations. He might never have succeeded were it not for the tireless advocacy of a group called Marshall Together, which brought hundreds of fire victims from neighboring towns together on the workplace messaging app Slack. The founder of the group, a lawyer named Tawnya Soumaroo, conceived it less as a charity or neighborhood association than a political lobby: She studied up on housing and insurance law, collected stories from her displaced neighbors, and lobbied legislators the way a trade group or farm bureau might do. As the fire survivors flexed their political clout, industry groups backed off, and Brown’s bills passed with overwhelming bipartisan support.

Extreme weather events don’t just destroy homes and buildings, they also alter how people relate to each other and to their government.

These Boulder suburbs are denser and wealthier than many wildfire-prone areas, and it’s likely thanks to that privilege that residents such as Soumaroo had time and resources to organize after the disaster. But many of the biggest reforms they passed are forward-looking rather than retroactive, which means the survivors of the Marshall Fire won’t benefit from them. Future fire victims in Colorado, though, will enjoy strong protections from predatory behavior by mortgage lenders and insurance companies, which could mean the difference between rebuilding in one year or five years.

It’s a powerful example of the dynamic we’re going to explore in this newsletter: Extreme weather events don’t just destroy homes and buildings, they also alter how people relate to each other and to their government. In Boulder, unlike in so many other places, that change was for the better.

A focus on fire

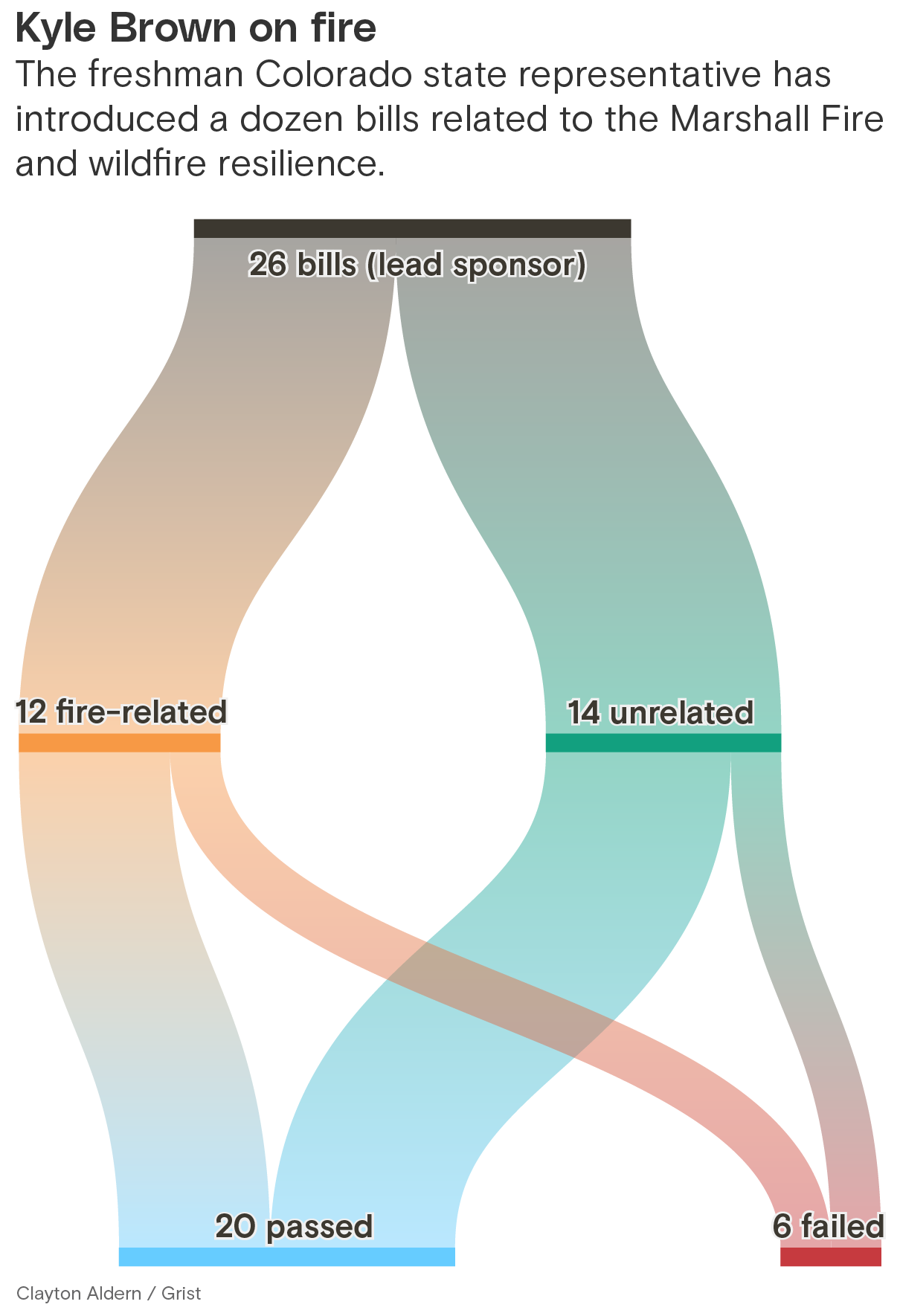

Kyle Brown was the lead sponsor on 26 bills during his first term as a Colorado state representative, and half of those concerned either the Marshall Fire recovery or future fire resilience. Even though these bills challenged established industries like insurance and banking, almost all of them passed, and with bipartisan support. Brown had just as much success with his fire legislation as he did with other legislation on more anodyne subjects, such as bingo permitting and virtual marriage ceremonies.

Read the full story on the surge of lawmaking that followed the Marshall Fire.

What we’re reading

Should Biden do more on heat?: U.S. Representative Rubén Gallego, a Democrat running in a close race for Senate in Arizona, blasted the Biden administration for not doing more to tackle the threat of extreme heat. Read more

Read more

Oregon wildfires become a campaign issue: As wildfires in Oregon burn thousands of acres, a Democrat challenger in the congressional district that surrounds Bend is attacking incumbent Representative Lori Chavez-DeRemer for voting against billions in wildfire-protection funding. Read more

Read more

Hurricane déjà vu in Florida: Hurricane Debby drenched northwest Florida last week, striking the same areas hit by Hurricane Idalia last year. The hurricane also brought flooding to Tampa as early voting began in Florida state primaries. Read more

Read more

Hot-weather voting in Tennessee: Election officials in Shelby County, which includes the city of Memphis, said hot weather was dragging down voter turnout in a primary election for state and local races in the area. Read more

Read more

Tim Walz, climate veep: Minnesota governor Tim Walz hails from a state that is immune from many big climate disasters, such as hurricanes and wildfires. But as my State of Emergency co-writer reports, Kamala Harris’ running mate has an impressive record of passing big green laws in his purple state. Read more

Read more