A California startup backed by the shipping giant Maersk wants to turn America’s farm waste into clean fuel for mammoth container ships. The company, WasteFuel, is working to build facilities across the country that produce “bio-methanol” from corn husks, discarded wheat straw, and other agricultural scraps — a low-carbon fuel produced in tiny volumes today.

Bio-methanol from these facilities would then travel by rail car to major ports, Trevor Neilson, chairman and CEO of WasteFuel, told Grist. Methanol-powered deep-sea vessels on, say, the U.S. West Coast would be able to refuel before sailing to China, Japan, or Vietnam with containers full of pet food, cotton, and scrap metal.

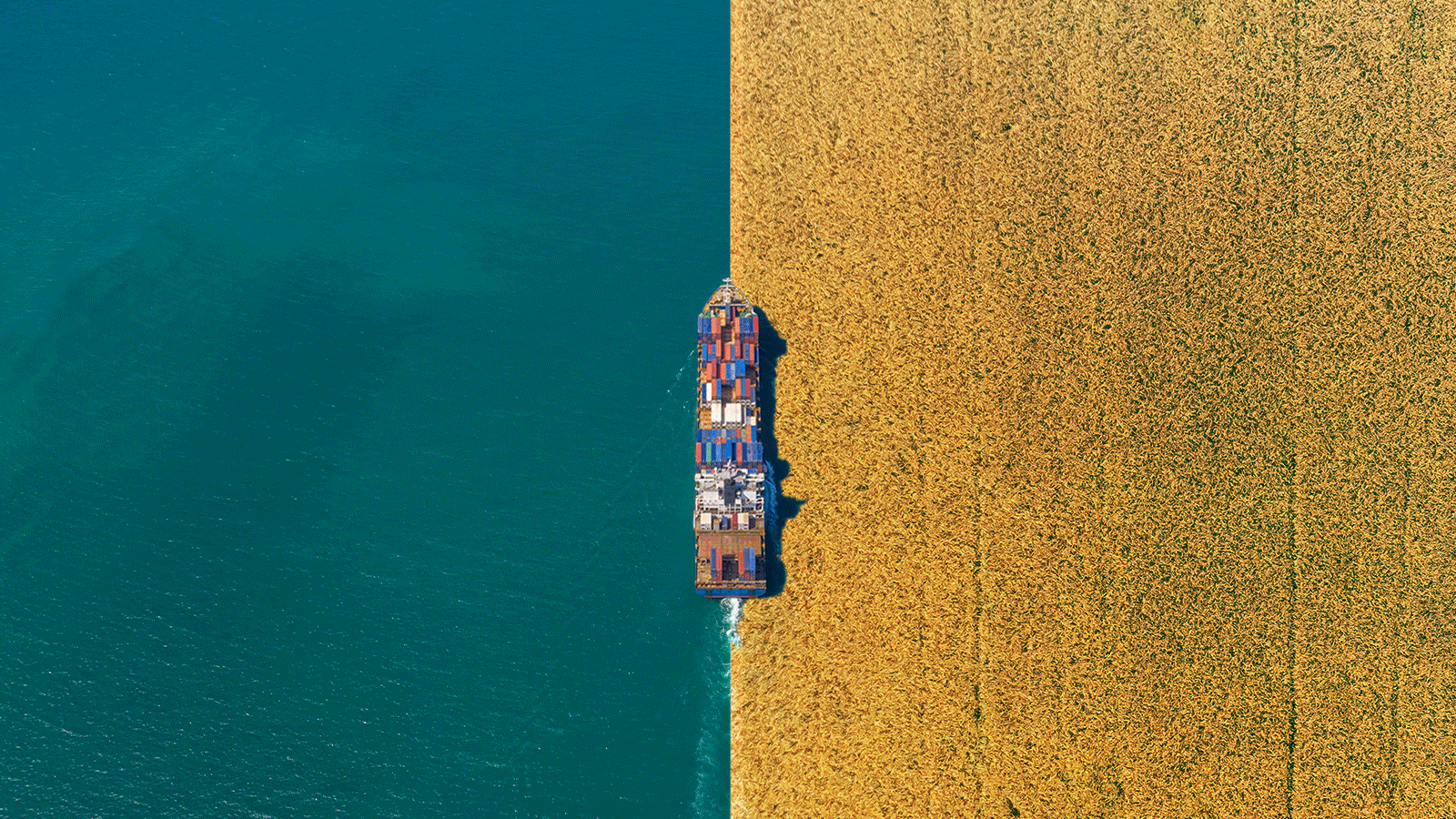

WasteFuel’s plans are part of a larger effort to cut emissions in the global shipping industry, whose vessels run almost exclusively on fossil fuels. Cargo ships contribute nearly 3 percent of the world’s annual greenhouse gas emissions — a number expected to climb as global trade expands. Within shipping, about 80 percent of emissions come from deep sea vessels. These oceangoing ships are particularly tricky to clean up because they often sail for weeks and cover thousands of miles between refueling, and have limited space on board for fuel tanks or battery banks.

“We have a huge opportunity to address the hardest aspects of decarbonization,” including long-distance and heavy-duty transportation, Neilson said from his home in Malibu, which overlooks the ship-clogged waters of Southern California. Record congestion around the ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles has driven a spike in air pollution from idling vessels and truck traffic.

For shipowners, bio-methanol is a promising alternative to dirty bunker fuel, because it can be used by converting engines in existing vessels. The problem is, only a handful of relatively small facilities make the fuel worldwide. Bio-methanol is also expensive to produce, costing up to seven times more than conventional methanol from fossil fuels, according to the International Renewable Energy Agency.

The first of WasteFuel’s planned bio-methanol facilities is expected to be completed within a few years, Neilson said, though the company hasn’t disclosed a location yet. Along with bio-methanol, WasteFuel plans to produce other low-carbon fuels for airplanes and freight trucks made from landfill garbage in the Philippines and Mexico, respectively.

For bio-methanol and other biofuels to play a meaningful role in reducing shipping emissions, clean fuel producers will need to drastically boost output and slash costs in the coming decades, said Eric Tan, a senior research engineer at the U.S. National Renewable Energy Laboratory, or NREL, in Colorado. “Scalability is very important,” he said, “and the fuel cost has to be competitive.”

In a recent study, Tan and his colleagues found the United States has ample amounts of feedstock that could be turned into biofuel — enough to supply a significant share of the global shipping industry’s annual needs by 2040. With technology improvements, supportive government policy, and more efficient ways of sourcing raw materials, U.S. producers could achieve the “critical mass” needed to make a dent in shipping’s carbon footprint, researchers said.

Companies will need to start using such fuels soon in order to stay on track for global climate goals, according to industry experts. The International Maritime Organization, the U.N. agency that regulates global shipping, aims to reduce the industry’s total emissions by half compared with 2008 levels by mid-century, and to fully decarbonize by 2100.

Last week, a group of giant retail companies including Amazon and IKEA said that, by 2040, they would only import goods on ships using zero-carbon fuels, including hydrogen and ammonia made with renewable electricity.

Shipping analysts say it’s not yet clear which low- and zero-carbon technologies will prevail as companies work to meet such targets. That uncertainty has prompted some shipowners to postpone ordering new vessels for fear of betting on the wrong solution.

Maersk, by contrast, is betting at least $1.4 billion on methanol-powered ships and supplies.

The toxic alcohol is primarily used to make chemicals for paints, plastics, and cosmetics, and nearly all of it is produced with natural gas or coal. When burned, methanol produces little air pollution. Only about two dozen ships use, or will soon use, methanol for fuel — mainly methanol-carrying tankers that draw supplies from their cargo holds. (In the 1990s, U.S. passenger cars like the Ford Taurus and Dodge Intrepid were built to use a methanol-gasoline blend before the fuel fell out of favor.)

From a climate perspective, however, methanol from natural gas is worse than commonly used fuels, like marine gas oil. So Maersk and other shipping companies are focusing on developing both bio-methanol and “e-methanol,” made with renewable electricity. According to the International Council on Clean Transportation, bio-methanol from plant biomass can reduce “well-to-wake” lifecycle emissions by 70 to 80 percent compared with marine gas oil.

In August, Maersk said it ordered eight mega container ships capable of running on methanol, with the first to join its fleet in early 2024. The Danish shipping company also plans to operate a methanol-burning vessel in Europe in 2023. The company has acknowledged one huge complication to those plans: Only about 220,000 metric tons of green methanol are produced annually, compared to the 330 million metric tons of fuel the shipping industry consumes every year.

“It will be a significant challenge to source an adequate supply of carbon-neutral methanol within our timeline to pioneer this technology,” said Henriette Hallberg Thygesen, CEO of Maersk’s fleet and strategic brands division, in a statement earlier this year. (The company did not return requests for comment.)

Maersk is backing WasteFuel and other fuel producers to fill the gap. In September, the company announced that it had invested in WasteFuel for an undisclosed amount, a move that made the shipping giant WasteFuel’s largest investor and put a Maersk executive on the startup’s board. Maersk is also investing in another clean energy startup, Prometheus Fuels, and has signed a contract to buy e-methanol from a facility planned in Denmark.

WasteFuel is talking to around 30 agricultural waste owners in and outside the United States and plans to eventually license existing technology from other developers, Neilson said. Bio-methanol can be made by fermenting organic materials in an anaerobic digester, or subjecting materials to high temperatures to produce synthetic gas, then processing it in a reactor. The latter process is especially capital- and energy-intensive, and neither is widely used in large commercial operations. “The question of scale is one that we all have to address,” he acknowledged.

According to Maersk, green fuels like bio-methanol will be two to three times more expensive than oil-based marine fuels. But because ships are so huge and carry so many containers on their decks, the final cost to consumers will be something like an extra 50 cents on a pair of running shoes, Neilson said.

There are other barriers to scaling up bio-methanol and other biofuels, said Tan, the NREL engineer. Collecting, cleaning up, and storing feedstock adds significant expense for fuel producers. And as chemical companies and airlines turn to biofuels to reduce emissions, the competition for waste feedstocks will heat up.

Neilson said that building bio-methanol facilities close to places where waste is collected, such as farms or landfills, can help reduce the cost of securing the raw materials. It also ensures that corn husks, food scraps, and garbage are fresh when they enter the facility, an important step because decaying organic materials emit methane. The sooner waste hits the system, the more methane can be turned into fuel — and the less winds up in the atmosphere as a potent greenhouse gas.

Noting the challenges facing WasteFuel, Neilson said a key difference between past and present attempts to boost bio-methanol supplies is that major companies are increasingly responding to pressure from activists to tackle climate change.

“That shifts the economics,” he said. “People in finance, people in consumer products are listening.”