There’s a war going on in Europe. Gas prices are sky-high. What’s an American to do? Well, search for electric vehicles, apparently.

According to Cars.com, online searches for new and used electric vehicles more than doubled in the roughly two-week period following the Russian invasion of Ukraine. That’s around the same time President Biden announced the U.S. would ban oil and gas imports from Russia, which produces a significant chunk of the world’s fossil fuels. As a result, gas prices across the U.S. have risen sharply, reaching an average of more than $4.30 a gallon, as of last week.

“When gas prices spike, searches immediately go toward more efficient vehicles,” Joe Wiesenfelder, executive editor at Cars.com, told E&E news.

Because they do not run on gasoline like a traditional combustion engine, electric vehicles, or EVs, spare their owners much of the stress associated with skyrocketing oil prices. The cost of charging an EV depends on a few factors, such as the model in question and the location you use to charge your vehicle. According to the Energy Department, a “tank” of electricity for a mid-size EV charged at home comes out to about $16. And, naturally, the benefits of EVs go beyond individual savings: Because electricity can be produced from renewable sources, EVs are appealing to drivers looking to mitigate their carbon footprints.

Even before the Russia-Ukraine conflict, electric vehicles were having something of a moment. Last summer, the “Big Three” American carmakers — Ford, General Motors, and Stellantis (the Dutch company that owns Chrysler) — announced it would aim for 40 to 50 percent of their new vehicle sales to be electric by 2030. Biden himself campaigned on the oft-repeated promise of 500,000 EV charging stations and announced plans for all federal vehicles to eventually go electric.

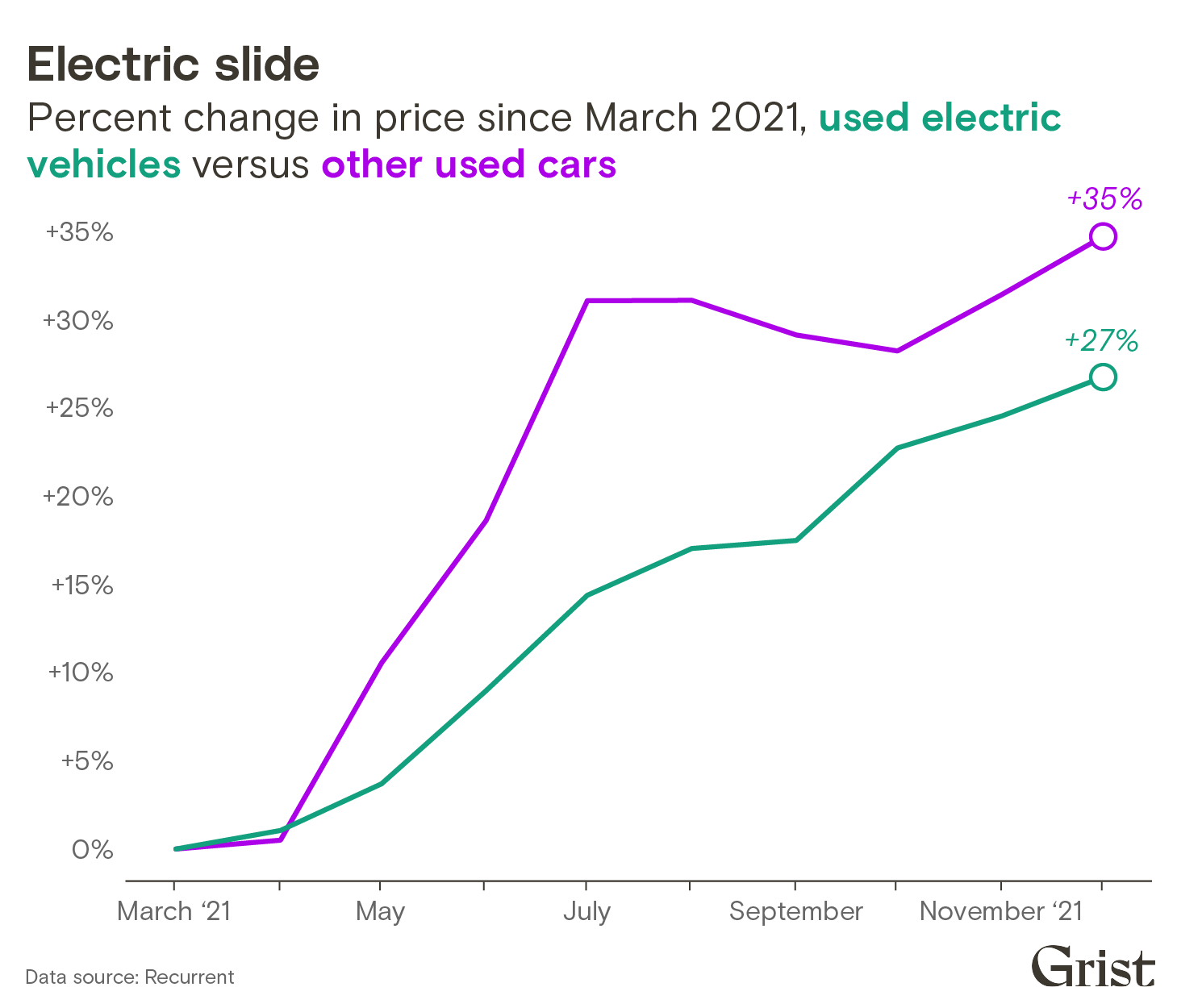

But despite those lofty goals, the path to widespread EV adoption has been surprisingly bumpy. EVs make up less than 1 percent of the country’s 250 million cars, trucks, and vans and only about 3 percent of new vehicle sales. One reason for the slow adoption may be cost: Although EVs are cheaper to drive, they are more expensive to buy upfront. That’s even true when you look at used vehicles. Over 70 percent of pre-owned EVs cost over $25,000. (The average price of a brand-new gas-powered vehicle in 2021 was just around $40,000.)

For lower-income people, the EV market is still largely out of reach. And supply chain issues have not helped the situation. Both used gas-powered cars and used EVs have gone up significantly in price since March 2021. And many of the federal and state programs designed to make EVs more appealing to consumers rely on tax credits, which disproportionately benefit the already wealthy. As a result, the energy savings from EVs are often only available to higher-income earners,

Electric vehicles have also met with some political resistance — even from within the Democratic party. At CERAWeek by S&P Global energy conference in Houston, West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin, indicated that he is “very reluctant to go down the path of electric vehicles” due to foreign policy worries.

“I don’t want to have to be standing in line waiting for a battery for my vehicle, because we’re now dependent on a foreign supply chain – mostly China,” he said.

While global supply chain issues pose real obstacles for EVs going forward, the Cars.com data seems to suggest many consumers disagree with Manchin’s reluctance to hop on the electric bandwagon. But for consumers who can’t yet afford to join those zero-emissions vehicle dreams, it’s more likely that they will have to turn to options to cope with the pain at the pump.