This story originally appeared in New York Focus, a non-profit news publication investigating how power works in New York state. Sign up for their newsletter here.

It takes about an hour to drive to the Canadian border from the tiny town of Croghan, New York. The area is heavily forested, on the edge of the sprawling Adirondack Park, and in the event of a wildfire, local volunteers bear responsibility for controlling and containing the blaze — even if it’s on state land. So far, they’ve had success.

“We’re lucky up here,” retired firefighter Steve Monnat told New York Focus. “When it gets dry, it doesn’t last very long.”

In his nearly five decades with the Croghan Volunteer Fire Department, Monnat never encountered a wildfire larger than a few acres. Few in New York have. But with the climate, that may change.

As heatwaves intensify and weather patterns swing between periods of heavy precipitation and prolonged drought, New York’s favorable, wildfire-stifling conditions may soon turn. Some argue that the present lack of fire increases the risk of deadly blazes in the future, and that intentional controlled burns are the best preparation. Others find the prospect too destructive, too risky.

“It is very likely that fire frequency and fire regimes are going to change here in the northeast, and that the chances of wildfire are going to increase,” said Andrew Vander Yacht, an ecologist at the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry in Syracuse. Extensive droughts and rising temperatures may dry forest fuels, he said, increasing the likelihood and severity of wildfires — unless New York burns the fuels first.

The state boasts 18.6 million acres of forested land, much of it publicly owned or constitutionally protected. Though many states perform extensive controlled burns to mitigate the risk of wildfires, New York prohibits the practice in its two largest forested regions. One of them, the Catskill Park, is nearly the size of Rhode Island. The other, the Adirondack Park, is larger than the Yellowstone, Everglades, Glacier, and Grand Canyon national parks combined. And unlike in those national parks — or the forested regions now burning in Canada — hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers live in and around state-protected woodlands.

Relatively few are on staff to manage them. New York employs about 130 forest rangers to cover 4.9 million acres of land — over 36,000 acres per ranger. They don’t just care for the state’s forests; their duties include law enforcement and search and rescue. Forest ranger attrition has plagued the state’s Department of Environmental Conservation for years, and some fear these personnel strains could inhibit the agency from carrying out a more involved fire management strategy.

In Croghan, about 50 volunteer firefighters put out the flames in town and on dec land alike. They range from high school students to senior citizens, some of whom maintain their membership solely to participate in the department’s social functions and no longer respond to emergencies. In the event of a major forest fire, they would need to call for additional help from downstate.

Fortunately, the department has not faced a major forest fire in living memory. “Never happened,” said Monnat. “Hopefully it never does.”

Not only does New York have a wetter climate than wildfire-prone regions of Canada and the American West, but the state’s tree species tend to be less susceptible to fire.

“Canada has large remote tracts of spruce, fir boreal forest,” dec spokesperson Jeff Wernick told New York Focus. “New York has some boreal forest in the Adirondacks, but it is segmented. New York has more temperate hardwood forests, which are a lot less susceptible to the types of fire Canada is having, especially after the spring green-up.”

Art Perryman, a longtime ranger who recently returned from fighting forest fires in Nova Scotia, is less sanguine. This summer, unprecedented wildfires in the historically wet Canadian province burned over 58,000 acres of land and displaced over 6,000 people. Perryman said that the similarities between Nova Scotia and the Adirondacks disturbed him.

“They have a very similar climate to us in terms of rainfall,” Perryman told New York Focus. “They’re essentially at the same latitude as us here in the Adirondacks and the fuel type is not all that different.”

Without consensus on whether proactive wildfire prevention measures — like underbrush-clearing burns — are prudent or feasible, the state’s plan is unchanged: Keep suppressing the blazes as they come.

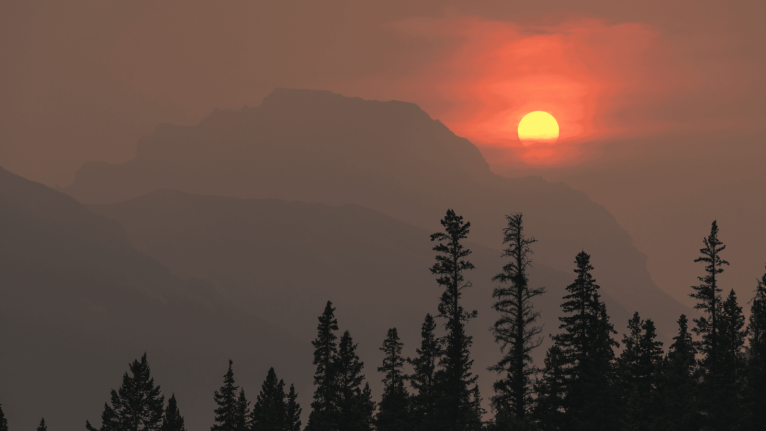

Before Canada’s wildfire smoke started to blow down this summer, forest fires rarely troubled New Yorkers. Wildfires seldom burn more than 3,000 acres in New York per year, passing mostly unnoticed by the state’s population.

That wasn’t always the case. In the early 20th century, upstate wildfires decimated hundreds of thousands of acres every year, poisoned waterways, and blanketed New York City in ash. Rampant logging littered forests with fuel, and the state’s booming railway industry provided ample sparks. In 1903, New York suffered 643 wildfires that together burned over 450,000 acres of land.

Prior to the arrival of European settlers, New York’s indigenous inhabitants used prescribed burns to clear underbrush. According to Les Benedict and Jessica Raspitha of the St. Regis Mohawk Tribe Environment Division, which manages the reservation’s 6,800 acres of forested land along the Canadian border, controlled burns aren’t just part of their people’s past. Soon, they may use them again to clear invasive phragmites — a common type of dry, grassy reed — that have spread throughout their tribal forests.

“The reeds grow very close together,” Raspitha told New York Focus. “They push out all the native vegetation that would grow around it.” If left undisturbed, phragmites multiply and accumulate from year to year — providing rich fuel for fires.

Forest managers like Benedict and Raspitha see controlled burns as a useful tool, yet they remain off limits in the Catskills and Adirondacks.

“We are so ignorant when it comes to fire management in New York state,” Ryan Trapani, director of forest services for the nonprofit Catskill Forest Association, told New York Focus. “I wish we were burning more.”

Not all environmentalists agree. For John Sheehan, director of communications for the conservationist nonprofit Adirondack Council, wildfires do not, and will not, pose a significant enough threat to justify controlled burns.

“We had 60 wildfires last year that burned almost a thousand acres in the Adirondacks,” Sheehan told New York Focus. “You double that you’re still not talking even a tiny fraction of the 6 million [acres] we have inside the park.”

Mismanaged, controlled burns can have devastating effects. In 2022, the us Forest Service lost control of a fire it’d set in New Mexico, accidentally destroying over 300,000 acres of land and displacing tens of thousands of people.

Benedict and Raspitha understand the risks and said their division will not perform any controlled burns without proper authorization, training, and preparation. “You need trained experts,” Benedict said.

A single controlled burn requires at least three people to perform. New York may not have the staff. The state’s forest rangers have expressed concerns that they do not have enough personnel to perform their existing duties, let alone any new ones.

“There’s not enough rangers,” said Dave Holden, an environmental activist and longtime resident of the Catskills region. “They’re underfunded for regular operations.”

But if you ask Perryman, the state has the money. He estimates that New York receives about $7,500 each time a ranger deploys out of state to fight wildfires, which he believes should finance a dedicated wildfire protection fund.

“It’s a pittance for New York state,” Perryman said. “But it’s very important … for our program and being ready for these large, destructive wildfires.”

Vander Yacht, who runs suny’s Applied Forest and Fire Ecology Lab, is also in favor of controlled burns. He points to a 2021 study that predicts the frequency of wildfires in New York will more than double by the end of this century.

The Catskills’s oak forests pose the greatest risk of burning in the near future, Vander Yacht said, and a major forest fire in the Adirondacks is less likely. But a blaze in that region could wreak immense destruction due to dense growth and underbrush accumulation — made possible by decades without fires.

Other states, including California, Florida, Vermont, and Pennsylvania, liberally employ prescribed burns to mitigate the risk of wildfires. In New York, they’re far less common, but not unheard of.

Sheehan lives in Albany, and he acknowledges the regular use of controlled burns near his home to mitigate the risk of wildfires in the Albany Pine Barren. But he worries that human intervention in New York’s protected forests could disturb the natural conditions that have long suppressed wildfires.

“Really the only period of time that we had major wildfire problems inside the [Adirondack] park was after a period of long deforestation,” Sheehan said, pointing to the dark history of exploitative logging in the 19th and early 20th centuries. “The forest floor got exposed to sunlight in ways that had never happened before, not because trees fell down or something in a storm, but because they were hauled away.”

In 1885 — spurred by the rapid decimation of the state’s woodlands — the New York state legislature established the Forest Preserve, which grew to include millions of acres in the Catskills and Adirondacks. Nine years later, at the 1894 constitutional convention, the Forest Preserve gained even stronger protections.

Article xiv of the New York state constitution states that the Forest Preserve “shall be forever kept as wild forest lands.” Sheehan believes the “forever wild” clause prohibits controlled burns in the Catskills and Adirondacks. Vander Yacht and Trapani also expressed doubts that the state constitution allows such measures in protected forests. But in a 1930 case, the state’s top court found that the “forever wild” clause exists to protect state forests, and therefore permits “all things necessary” to preserve those forests, including “measures to prevent forest fires.”

Wernick, the dec spokesperson, said state environmental conservation law grants the agency “broad statutory authority” to suppress fires on state lands, and that the dec may determine which fire suppression strategies — including controlled burns — are appropriate and warranted.

The dec does not currently allow prescribed burns in the Catskills and Adirondacks, and it hasn’t shown any inclination to use them in the future.

Some of the agency’s frontline staff are pushing to change that. Leading a group of rangers who helped fight this summer’s Canadian wildfires, Perryman plans on lobbying dec leadership to revamp the agency’s wildfire prevention policies — advocating for the use of prescribed burns, additional training for rangers and firefighters, and an update for the state’s aging inventory of forest firefighting equipment.

Perryman told New York Focus he reached out to dec Commissioner Basil Seggos, but he has yet to receive a direct response.

Even absent major forest fires, volunteering with a rural fire department is “a busy little way of life,” according to Monnat. Holden worries that unless New York revamps its wildfire management policies, the state’s firefighters may find themselves much busier.

Holden acknowledges that many voters and policymakers remain unconvinced that New York needs to do more to mitigate the risk of wildfires in the state’s protected forests. His pitch is short and to the point.

“What would you rather have?” Holden asks. “Us clearing your property, preventing it from burning up? [Or] would you rather have firefighters coming on your property, whether you want them or not, because it’s burning up?”