Let’s turn NIMBYs into YIMBYs.Photo: Eddie CodelThis post originally appeared on Energy Self-Reliant States, a resource of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance’s New Rules Project.

Let’s turn NIMBYs into YIMBYs.Photo: Eddie CodelThis post originally appeared on Energy Self-Reliant States, a resource of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance’s New Rules Project.

Last month, Grist’s Jess Zimmerman noted sarcastically that “Money is a miracle cure for ‘wind turbine syndrome.'” It is. And environmental advocates frustrated by the (spurious?) health and aesthetic complaints raised by not-in-my-backyard (NIMBY) actors would do well to consider why.

The implication of her post (and this attitude in general) is that we can’t green our energy system without sacrifice. Getting to big carbon reductions will require enormous new renewable energy development and it will often happen in places where land was previously undeveloped (note: see this counter-argument). The folks who live there, the NIMBYs, need to do their share.

It’s awfully easy to offer sacrifice when you’re not on the altar. And it’s worth considering what’s really behind the “syndrome.”

In a recent study by the ever-methodical Europeans, they found that opponents to new wind and solar power have two key desires: “people want to avoid environmental and personal harm” and they also want to “share in the economic benefits of their local renewable energy resources.” It’s not that people are made physically ill by new renewable energy projects. Rather, they are sick and tired of seeing the economic benefits of their local wind and sun leaving their community.

In a recent study by the ever-methodical Europeans, they found that opponents to new wind and solar power have two key desires: “people want to avoid environmental and personal harm” and they also want to “share in the economic benefits of their local renewable energy resources.” It’s not that people are made physically ill by new renewable energy projects. Rather, they are sick and tired of seeing the economic benefits of their local wind and sun leaving their community.

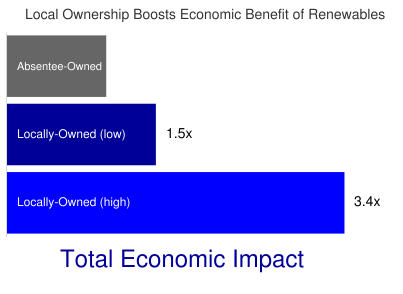

Such opposition is perfectly rational, since investments in renewable energy can be quite lucrative (private developers and their equity partners routinely seek 10 percent return on investment or higher). And the economic benefits of local ownership far outweigh the economic colonialism of absentee owners profiting from local renewable energy resources.

Of course, NIMBY-ism only sometimes manifests itself as an economic argument, and there’s a good reason for that, too. In the project development process, there are precious few opportunities for public comment, and almost all of them represent up-or-down votes on project progress. None offer an opportunity to change the structure of the development to allow for greater local buy-in or economic returns. And no project will be halted simply because it isn’t locally owned. Projects can and have been stopped on the basis of health and environmental impacts. Enter Wind Turbine Syndrome.

There are alternatives. In Germany, Ontario, Vermont, and Gainesville, Fla., local citizens can use a renewable energy policy — a feed-in tariff — that offers them a guaranteed long-term contract if they become a renewable energy producer. This contract guarantees a reasonable, if small, return on investment and helps them secure financing. In Germany, the program’s simplicity means that half of their 43,000 megawatts of renewable energy are owned by regular farmers or citizens.

In Ontario, the provinicial clean energy program specifically requires project developers to use local content, guaranteeing a higher economic benefit for the province in exchange for its robust support for renewable energy. The program is forecast to generate 43,000 local jobs in support of 5,000 megawatts of new, renewable energy.

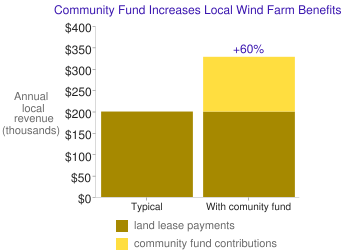

In the United Kingdom, public officials are piloting a “community wind fund” program for all new wind projects. Under the program, each wind project must pay in £1,000 per megawatt (~$1,600 per megawatt) per year, for 25 years, into a community fund where the project is located.

The impact for the community is significant. Compared to the typical land leases (often $5,000 per turbine for the host landowner), the community fund payments would increase local revenue by over 60 percent, with the additional funds spread to the entire community rather than just the lucky turbine hosts.

The impact on turbine owner net revenue is small but not negligible, reducing the net present value of the project by about 3 percent.

The impact on turbine owner net revenue is small but not negligible, reducing the net present value of the project by about 3 percent.

It’s not that any of these policies represent the silver bullet for local opposition to new renewable energy projects, but they do address the underlying problem.

The truth is that many people are frightened of being left behind by the clean energy revolution or angry that their local resources are tapped without commensurate local benefit. They find that there’s no way to be heard in the (democratic?) process without resorting to tangental arguments about health and viewsheds.

NIMBY has been misunderstood by the clean energy community. It is not a knee jerk, it’s a market failure.

When citizens see a new wind or solar energy project, it shouldn’t be from the sidelines. They should see it from the front seat, where they have hitched their wagon to environmental and economic progress by investing in a local energy project.

Our energy policy should make that possible. It doesn’t.

Federal tax policy makes it very difficult to share renewable energy tax incentives among multiple investors. Federal and state tax-based incentives preclude many local organizations (nonprofits, cities, schools) from owning wind turbines or solar panels. And utility billing rules make it nearly impossible (in most states) to share the electricity output from a shared project that isn’t utility-owned.

There are brilliant examples of entrepreneurs overcoming these barriers to install community-based projects. Developer Dan Juhl and others have a record of success with community wind in Minnesota. The Clean Energy Collective is piloting a new community solar program in Colorado.

There are even some policy ideas bringing hope. Virtual net metering laws in eight states allow for sharing electricity output. Colorado’s solar gardens bill enshrines a small amount of community solar.

But the theme is one of triumph over adversity, with local ownership the exception rather than the norm. And without better energy policies that give locals a chance to buy in, the wind turbine syndrome epidemic will likely continue.