This is part of a series of posts on distributed renewable energy that will be posted to Grist. It originally appeared on Energy Self-Reliant States, a resource of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance’s New Rules Project.

I had a conversation with a wind developer yesterday and was talking about the difference between putting together large projects (over 80 megawatts) compared to distributed generation wind projects (80 megawatts and under). I mentioned that we have a deep interest in understanding the economies of scale of renewable energy projects and he replied, “Economies of scale are bull****.” He noted that large wind projects require significant development costs that smaller projects don’t encounter (including many more landowner negotiations and permits) and that installation and maintenance services are sufficiently widespread for any sized project to find services.

It’s not entirely true that bigger projects have no economies of scale, but these two charts illustrate the larger point: Most economies of scale in solar photovoltaic (PV) and wind power are captured at a relatively small size.

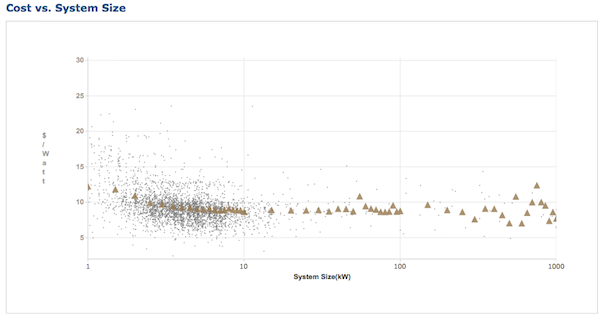

The first chart is from the California Solar Statistics website, and draws on data from over 70,000 solar PV installations in California since 2005:

Clearly, solar PV installations of 10 kilowatts have captured more of the economies of scale for solar PV. Costs may fall slightly for much larger projects, but the smaller number of projects makes it hard to see trends (interesting note: there seem to be as many > 100 kilowatts solar projects costing over $10 per watt as there are under $8 per watt).

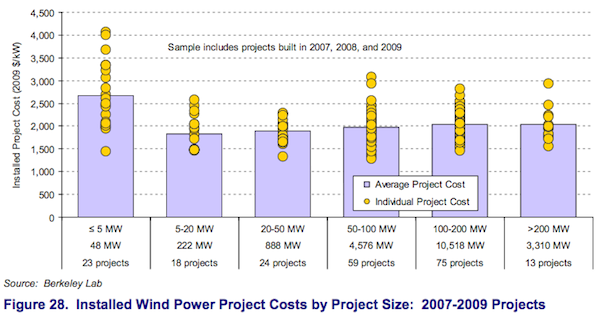

The second chart comes from the 2009 Wind Technologies Market Report by Ryan Wiser and Mark Bolinger (which is a must-read):

The wind data is even more striking, with the lowest average project cost found in the projects with just a handful of turbines (5-20 megawatts of capacity), with costs steadily rising for larger projects. Certainly there’s an advantage to having more than one turbine, but less so for growing the project much larger than 10 turbines.

This data should inform renewable energy policy. If modest-scale, distributed renewable energy projects capture most (or all) economies of scale, then the opportunity to place these projects close to load may reduce the need for new, long-distance, high-voltage transmission lines. It means more renewable energy can come online faster and with fewer political battles.

These smaller-scale projects are also the appropriate size for local ownership (which provides twice the jobs and one to three times the economic impact of absentee ownership), allowing more the economic benefits of renewable energy development to accrue to the host community.