Dear Umbra,

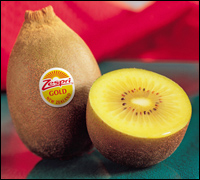

Yesterday in the grocery store I saw a “golden kiwi.” Is there really such a thing? It was over twice the size of a regular kiwi and the familiar fuzz was not there. It was almost as smooth as a nectarine. When I inquired of the produce representative, she told me that it was a “natural” unaltered fruit and that I could taste it if I wanted to. Naturally, I declined. I am very leery of this strange new fruit. And have you seen the pluot? It looks somewhat like a transparent Macintosh apple crossed with a plum of some sort. Truly, that’s a strange fruit.

Can you shed some light on some of the new fruit that has been showing up lately?

Winnie

Houston, Texas

Dearest Winnie,

Yes. The “new” fruit you see at the store or market is either fruit already common in another part of the world and just making its way to our shores or fruit newly developed by horticulturists. (It’s not, as you might fear, genetically modified. As far as I’ve been able to suss out, papayas are the only GM fruit that might be sold in the produce section of your local grocery vendor.)

Who are you calling funny-looking?

Photo: Zespri International Ltd.

The kiwifruit (the one you know and love) is itself a good example of a “new” old fruit. Native to China, Actinidia deliciosa was brought to New Zealand early in the 20th century, where it was known as Chinese gooseberry. Chinese gooseberries, renamed kiwis after the New Zealand bird, started making real inroads in the U.S. in the 1950s. They were considered new here, but were old to folks living in the Yangtze valley.

The pluot, in contrast, is an example of a fruit newly developed by horticulturalists. This strange-sounding fruit is a plum-apricot cross laboriously developed by physically cross-pollinating trees and patiently waiting for a viable fruit.

Likewise, the gold kiwi is also a product of horticultural breeding. New Zealanders took fruit seeds from wild vines in China that produced small yellow kiwis and spent 11 years, beginning in 1987, cross-pollinating and grafting them with green kiwi vines in order to create the sweeter gold kiwis that are now showing up in your fair city. Grafting, an ancient technique, can be crudely described as cutting a twig from one tree and sticking it into a hole in another tree. The twig provides the fruit, the tree provides the fuel. Every commercial apple you’ve ever eaten came from a grafted tree. It’s our little way of controlling nature to make sure we get an edible fruit.

On occasion, a new fruit will appear on its own. The first nectarine appeared as a “sport,” or freak, peach. Enterprising orchardists began grafting off that sport, and my favorite stone fruit was the result.

When you see a “new” fruit or veggie, don’t be mistrustful. Careful selection and purposeful manipulation of pollination are as old as agriculture. Supermarket broccoli has been selected and bred for machine harvest and shelf longevity. It was a “new” broccoli once. Although we may criticize aspects of modern agriculture, it would be ridiculous to pretend we could (or should) go back to hunting and gathering — or to assume that all of it was bad for us and bad for the environment. New fruit isn’t necessarily an ecological menace. And it’s often quite tasty.

Juicily,

Umbra