It’s something of a miracle that Turkey Creek, Itâ€

In more recent years, Turkey Creek has suffered almost constant environmental and corporate threats, including natural (but likely human-fueled) disasters like Hurricane Katrina, and politicians and developers who ignore the people and animals who inhabit the place, victims of the geography of erasure.

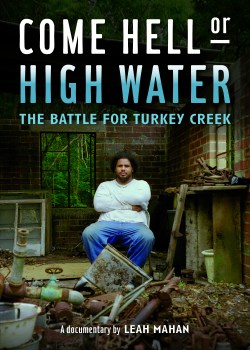

A just-released documentary, Come Hell or High Water: The Battle for Turkey Creek, distilled from 12 years of footage, is the story of this Gulf Coast community’s survival. The 56-minute feature from filmmaker Leah Mahan premiered Oct. 13 at the New Orleans Film Festival, where it walked away with the Audience Award for Documentary Feature. (Disclosure: I worked with Mahan on the Bridge the Gulf blog project in 2012.)

A just-released documentary, Come Hell or High Water: The Battle for Turkey Creek, distilled from 12 years of footage, is the story of this Gulf Coast community’s survival. The 56-minute feature from filmmaker Leah Mahan premiered Oct. 13 at the New Orleans Film Festival, where it walked away with the Audience Award for Documentary Feature. (Disclosure: I worked with Mahan on the Bridge the Gulf blog project in 2012.)

On a deeper level, the film is an exploration of a topic I’ve explored on Grist before and plan to continue covering: How civil rights activists become environmental activists, and vice versa — if there was ever really a difference to begin with.

The narrative in Come Hell or High Water is mostly told through the eyes of Derrick Evans, a burly Turkey Creek native son with an ever-expanding passion for and vocabulary of preservation. He tells us early in the film that his “great-grandfather’s grandfather” founded the community, named after an actual creek in Gulfport where wild turkeys roamed, in the late 19th century.

The documentary begins in 2001, when Evans lived in Boston, teaching history to middle school and college students. In one of the opening scenes, we see Evans working with a black teen on a city lot Evans converted into a garden. When his younger helper accidentally pulls collard greens while weeding, Evans puts the mistake into historical context: “These are the results of the Great Migration,” he says, referring to the massive, early 20th century exodus of African Americans from the South to seek jobs and escape Jim Crow.

Collard greens were a cultural staple of African American lives in the South. But for Evans, the consequence of black people’s southern uprooting to northern concrete jungles is that they were separated from nature and the land they cultivated when in Africa, and later as enslaved Africans, and finally as free share-croppers and farmers.

This lost heritage, and an insatiable urge to research his Mississippi ancestors, calls Evans back to Turkey Creek where he finds that developers have built over the community’s cemetery and plan to do the same over nearby wetland that has protected the community from flooding for decades. What unfolds over the next hour is Evans’ transformation from historical archivist to activist, as Evans works with fellow community members over the course of a decade to protect a community that believed itself free until Gulfport planners and developers encroached upon its natural landscape and residents.

Evans was an environmentalist when he was teaching the shorty in Boston the difference between collards and weeds. But in Turkey Creek, it’s not just an issue of educating someone about botany — it’s about pushing back against the will and intentions of those who want to wipe his home slam off the map.

Gulfport City Councilor Kim Savant, who helped draft a 25-year expansion plan for the city, tells Mahan, “It never occurred to me that there was actually a community there [at Turkey Creek].” Gulfport Mayor Ken Combs (now deceased) calls the black Turkey Creek residents “dumb bastards” for opposing the plan, because … you know, jobs. His quote makes the front page of the local newspaper.

Nor do Gulfport officials think much of the creek itself, where generations of black residents fished to feed their families, learned to swim, and were baptized. Savant says the creek, which is now polluted by runoff from expanding Gulfport commercial operations like its airport, is not a creek at all, but a “drainage channel.”

The main developer, Butch Ward, says the land he wants to pave over isn’t actually wetlands because … well just because he says so: “It’s somebody else’s definition of a wetland.” That “somebody else” is the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, which designated much of the Turkey Creek watershed, including a large part of Ward’s private property, as wetlands, meaning he will need permits to develop on them.

The labeling exercises here show that it is often wealth and power that claim lingual correctness in these land struggles, and it’s not just semantic. City plans and policies are created and approved based on this language. If a city councilmember says Turkey Creek is just a toilet bowl, then it’s easy for them to flush it away.

The documentary shows Turkey Creek residents speaking up, though, using their own empowering language, claiming the land as their home. Gulfport talk radio host Rip Daniels calls Turkey Creek “an environmental marvel … not a trench.”  The community recruits the Sierra Club, Audubon Society, and other environmental groups to demonstrate that the creek is also critical habitat for rare plants and birds.

“It’s not drainage,” says Evans. “It’s about the irreversible consequences of pro-development tunnel vision in a wetland that is historically valuable and endangered.”

The language of power and oppression is omnipresent in Come Hell or High Water, and it doesn’t get any better as Katrina pounds Gulfport in 2005. Still no better when the BP oil disaster happens five years after that. The documentary captures Turkey Creek’s responses to all of these tragedies — and a few remarkable victories against the powers that be.

By the end of the film, the difference between Evans’ civil rights and environmental advocacy is academic, at best. Filmmaker Mahan told me that during Evans’ 12-year mission in Turkey Creek, he became a certified master naturalist through classes provided by the Audubon Society. In the last quarter of the movie, Evans is talking about the “facultative properties” of plant life and how they are indicative of wetland presence, despite how developers label the land.

It’s not civil rights jargon by any stretch, but like civil rights philosophy, it pushes back against the language of oppression.