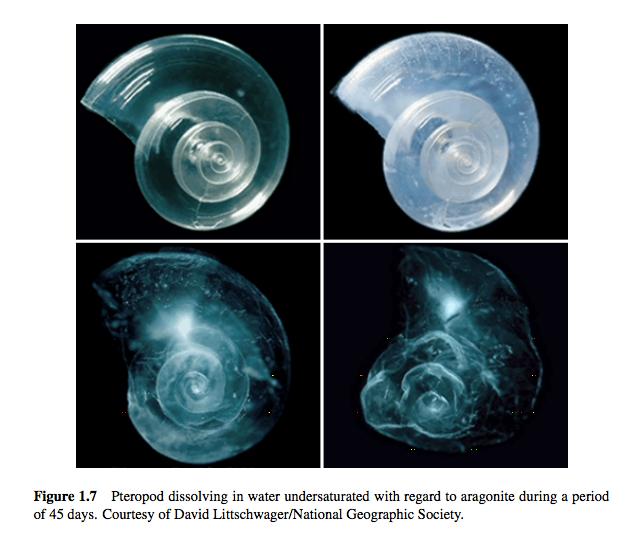

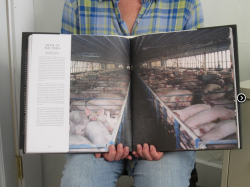

Mary Beth Sweetland, who oversees undercover investigations for the Humane Society of the U.S., holds a photograph of the kind of facility where her employees often work.

She may be the only boss in America who will tell you during a job interview that you really, truly, almost certainly don’t want the job. Go home and think about it, she might say. Reconsider if you need. Imagine what you’ll be doing.

The job, she’d tell you, will involve feces and dirt and animals too sick to move. It will be lonely, smelly, depressing, and exhausting. You’ll be spending weeks, perhaps months, inside an American factory farm — the kind of place that causes manure to leach into waterways and high concentrations of methane to spew into the air — witnessing alleged acts of animal cruelty and environmental degradation that you can do little, if anything, about. A hidden camera will be your only connection to the outside world, and she — your boss — will be your only confidante after you get off work, the only person who will understand if you break down, weep, or just want to quit.

Still want to be an undercover investigator for the Humane Society of the United States? If so, Mary Beth Sweetland, the organization’s senior director of investigations, would start investigating you. From her Vermont home, she’d make sure there’s very little trace of you on the internet, that your name is not associated with any animal rights cause, and that you pass a background check. If she’s confident that the country’s largest animal welfare organization can trust you with a sensitive undercover investigation, you’d be hired.

You’d then join a small band of gutsy risk takers trying to be the eyes and ears of the public inside agricultural facilities that are very much closed to the public. Right now, and at any given moment, a handful of HSUS investigators are working undercover — not only in factory farms but in puppy mills, laboratories, and zoos — and Sweetland is their den mother.

“I admire the heck out of them,” Sweetland said recently. “I should probably tell them that more. I wish they could get the recognition that’s due to them.”

Her investigators may be anonymous, but their work is not. Policy developments that have resulted from HSUS factory-farm investigations are well-known in agricultural circles:

- After mistreatment of cows was uncovered by a 2008 investigation at the Hallmark slaughter plant in Northern California, downed beef cattle — cows too sick or injured to walk — were banned from the food supply; they are now euthanized instead.

- When an undercover worker at the Bushway slaughterhouse in Vermont exposed mistreatment of young bull calves, the federal government approved a tentative ban on downer calves in the meat supply; HSUS hopes the rule will be finalized soon.

- A number of undercover videos taken inside industrial pig facilities has led to a cascade of corporations announcing they will no longer sell pork raised in gestation crates.

In fact, the increase in major HSUS investigations over the past few years — as well as undercover investigations by other organizations such as Mercy for Animals and Compassion Over Killing — has coincided with an increase in proposed “ag-gag” bills in various state legislatures. These bills, supported by large-scale agriculture, seek to make the photographing or videotaping of agricultural facilities a misdemeanor, or in some cases a felony. They have already passed in three states (Iowa, Missouri, and Utah) and more are expected to come up for a vote in 2013.

Although these bills may be a sign of HSUS’s success in undercover operations, the organization opposes them strongly because they could make it harder to recruit people to work undercover. Applicants would face the threat of significant fines or prison time, on top of all the other hardships that come with an undercover job. As Matt Dominguez, the HSUS public policy manager for farm animals, puts it, referring to Sweetland, “These bills could potentially make her job obsolete.”

***

Grainy video clips of the dank and hidden places where most American meat is raised may appear on our Facebook feeds or television screens. We may watch them, we may not. But one person who never has a choice is Sweetland. Every day, she or her assistant must review the raw video footage and written log notes sent in by her investigators via postal mail or email. She then selects video clips and notes that she thinks HSUS could build a legal case around and forwards them to lawyers and senior staff at HSUS’s Washington, D.C., headquarters.

When material is coming to her steadily, Sweetland can spend half her workday or more peering into the most wretched corners of factory farms. Of course, not all industrial farms harbor employees who could be brought up on animal cruelty charges, but Sweetland reviews footage from places that potentially do. She often wrestles with when to pull an investigator out of a facility because the cruelty has gotten so bad. (She prefers that they stay as long as it takes to get adequate evidence for a case.)

At age 58, she has five dogs who comfort her when the footage is searingly sad, but she has no other coping mechanism except the will to continue.

“I still cry after all these years,” she says. “I can’t help it. But it doesn’t make me want to give up. It makes me want to put someone into the next place.”

Her investigators rarely cry. Sweetland says they’re thick-skinned individuals who are willing to take the physical risk of working with aggressive, highly stressed animals, and the psychological risk of being busted by their employer. Some of them do it for their love of animals or commitment to the animal protection movement, others do it because they’re adventurers, while others do it because it’s a paid job. All of them apply for their farm jobs using their real name, and HSUS makes sure that everything about their employment is above board.

The investigators tend to be solitary folks, too, people who can live in the middle of nowhere (where factory farms tend to be) and who can tolerate being unable to chat with fellow workers about who they really are. Sidling up to the local dive bar may be the only thing investigators can do for companionship. Sweetland tries to talk with them every day.

Yet since she was put in charge of investigations four years ago, she says none of her investigators have taken up the HSUS on its offer of free counseling.

“Overall they are different breed of person,” Sweetland says. “I look at them as not having a missing compassion gene but just able to see it, document it, and move on.”

The real workers in factory farms often can’t move on. Like most low-wage employees in rural areas, they may not have the means to leave a job, as demoralizing and disturbing as it may be. Sweetland has learned from her investigators that workers sometimes take out their personal frustration and anger on the animals they handle. Though not excusable, Sweetland says it’s understandable. She and her investigators often feel compassion for the very people who may face criminal charges as a result of their investigation.

“They have to be prosecuted,” Sweetland says. “There’s a law, they broke the law, and without prosecution there’s no deterrent.” But, she says, “Can you imagine the day-in and day-out hardships of their lives? Hearing about some of their histories, you can tell the really bad apples from those who are just caught in a never-ending cycle of despair.”

Beyond animals and workers, there’s another victim of factory farms — the environment. Sweetland foresees expanding investigations by instructing her investigators to capture environmental crimes, in addition to animal abuses. “Traditionally this issue has been approached separately by environmental and animal welfare advocates,” she says. But if a facility begins illegally pumping its waste products into nearby ditches or streams, or feathers and dust begin falling from ventilation fans like snow, her investigators will be there to capture it.

A longtime vegan, Sweetland — who speaks in a compassionate, measured tone and prefers to deflect attention from herself onto her investigators — came to the HSUS after working for 18 years at People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals. For much of that time she was head of their investigations unit. Before that, she didn’t want to watch undercover videos of factory farms, but when she finally did, she decided to give up meat once and for all. She realizes that some people who watch undercover videos respond by switching to humanely raised meat instead, and she believes they are an integral part of the factory farm movement.

What would she say to that large swath of the American public who prefers to change the channel or click to a different website whenever a difficult factory farm video comes into view?

“I’d say that if they consider themselves a humane and compassionate person, they must force themselves to look, not just satisfy themselves with self-assurance that they know what it’s like. They don’t know what it’s like, until they see it with their own eyes.”