Dennis Derryck, founder of Corbin Hill Farm.

The same week I interviewed an author who dismissed local food as nothing but “a niche product for upper-crust consumers,” I learned about a project in New York City that directly challenges that assumption. The folks behind Harlem-based Corbin Hill Farm don’t see sustainably grown local produce as a passing craze for the foodie elite; on the contrary, they’re figuring out a way to make it accessible to low-income communities on a large scale.

Founder and longtime Harlem resident Dennis Derryck has long been aware that people in his community and the nearby South Bronx don’t have much access to good, fresh food. But when it came to solutions, as he saw it, “all these small and beautiful things had very little impact. School gardens, rooftop gardens, educational programs — at the end of the program, where was the parent or the kid supposed to go?”

Derryck saw promise of more lasting change in the community-supported agriculture (CSA) model. But a traditional CSA design — in which members essentially invest in a local farm by paying a large share at the beginning of the season — wouldn’t work for neighborhoods where many residents live on food stamps and struggle to make rent on time. So Derryck tweaked the model to make sense for low-income consumers: Corbin Hill shareholders pay only a week in advance, can put their shares on hold at any time, and can use any form of payment — including food stamps. The program caters to neighborhood cultural tastes by including items like cilantro, tomatillos, and collard greens whenever possible, and every box comes with recipes written in both Spanish and English.

The actual Corbin Hill Farm sits on 95 acres Derryck owns in Schoharie County, N.Y. Eleven initial investors provided the start-up funds, and 75 percent of that money, Derryck notes proudly, came from African Americans and Latinos; 51 percent from women. “The investors should look like the community,” he says.

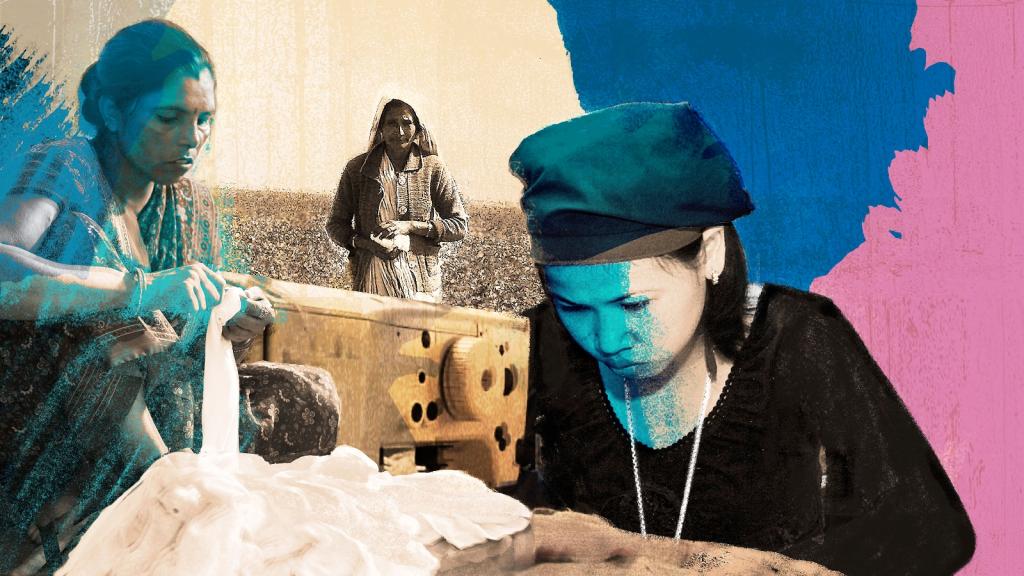

A typical medium-sized farm share.

Originally, the plan was for that farm to provide the bulk of the food for urban shareholders, but Derryck soon realized the operation would scale up much faster by sourcing from a network of producers in the area. Now the food delivered to the city comes from a cooperative of 15 farmers — many of them young — who meet every January to devise a harvest plan for the season. Just as Derryck takes seriously the needs of the urban population Corbin Hill serves, he also stresses his commitment to the farmers: They’re paid equally and on time, and when mapping out the harvest plan, crops are allocated first to the smallest farms, which are most vulnerable.

The first year the farm share was up and running, the goal was to reach 175 shareholders. It had 195 the first week. The second year saw an average 450 shareholders (because people can opt in or out at any time, the numbers fluctuate a bit throughout the season). This, the third year, Derryck says they’re averaging 750 shareholders so far. Clearly, he says, “it has struck a chord.”

Shareholders pick up their farm shares at one of 21 sites in Harlem and the Bronx. “Our goal is 150 sites, so nobody has to walk more than three or four blocks,” Derryck says, pointing out that having to pay upwards of $5 to ride a bus or train to pick up the food would negate its affordability. (And it really is affordable, as CSAs go: $15 for a medium box or $25 for a large.) Most of the sites are in schools, churches, and social organizations — institutions already primed for community outreach, which could help explain the farm shares’ rapid growth.

“Why are we succeeding? It’s very straightforward,” Derryck says. “We provide quality. And it’s affordable. And accessible.”

How, I wanted to know, was Corbin Hill Farm able to make this work, when an oft-discussed drawback to supporting small, local farmers is the premium eaters must pay for quality and transparency? Not so fast, Derryck cautions: Corbin Hill Farm is not a profitable operation yet. It will need at least 1,200 shareholders to break even. But at the rate the program has been growing, that doesn’t sound out of reach.

Shareholders at last year’s annual trip to the farm upstate.

If it works, Corbin Hill Farm could be a great example of the real impact investment in local food can have when both growers and eaters find power in numbers. Farmers working together upstate benefit from a streamlined distribution process and a guaranteed market; and the more city people buy in, the easier it is to keep prices affordable. And the program also creates a connection between urban and rural communities that are otherwise worlds apart. Shareholders have taken trips to the farms (the program provides transportation), and Derryck said they hope to start having farmers come down to visit city distribution sites, too. Last year, when Hurricane Irene wiped out the two largest farms’ crops, shareholders pitched in with donations.

Derryck doesn’t plan to stop at the 1,200 people he needs to make it profitable. “I believe we can grow this to 5,000 people. Once you get to that scale, people in the community begin to take notice,” he says.

And people outside the community notice, too. Corbin Hill Farm can serve as a model for other neighborhoods to adapt to fit their needs. In the end, it might just show local-food skeptics that good food is only exclusive if you refuse to change the paradigm that keeps it that way.