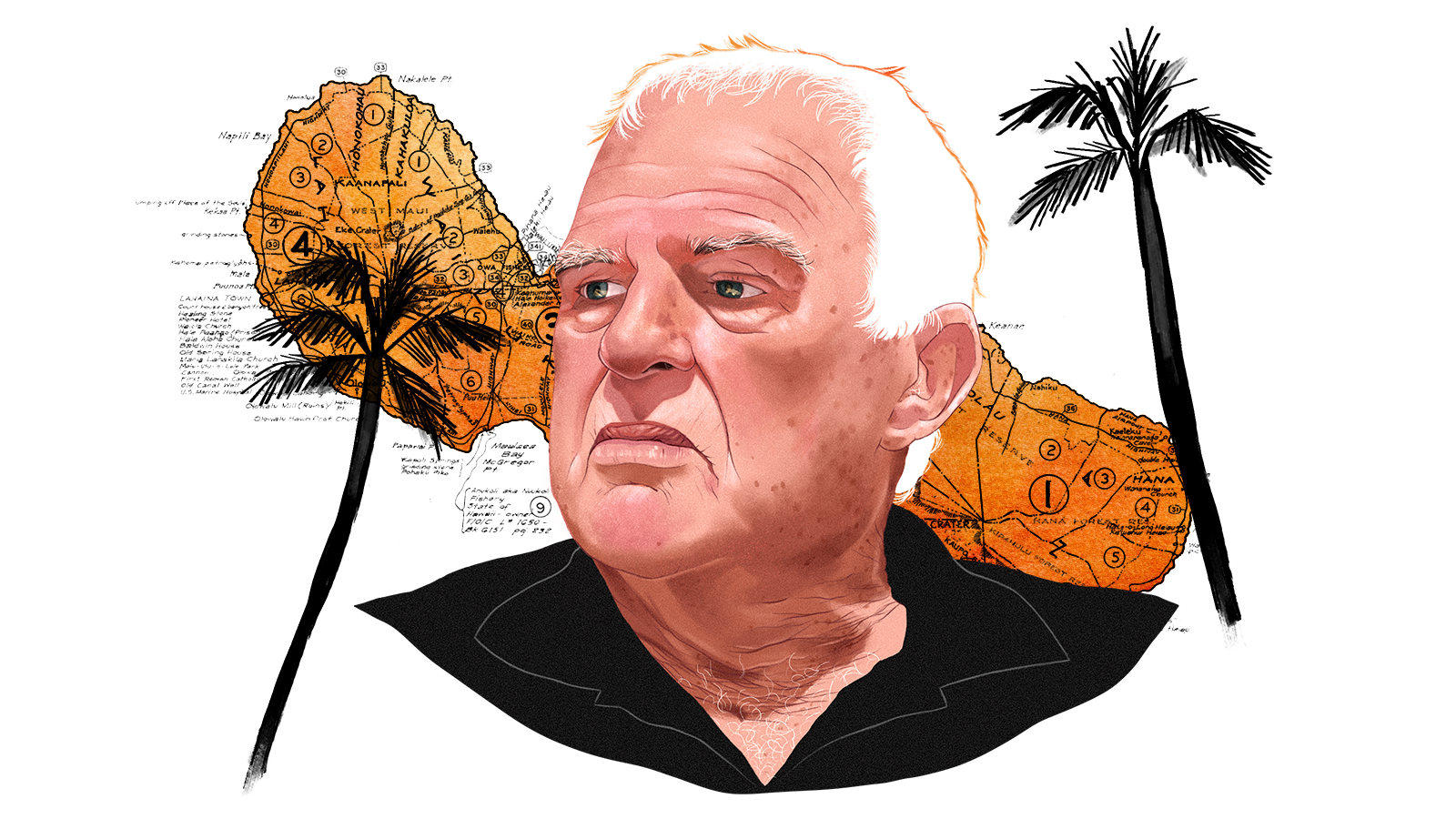

On the evening of August 8, hours after a wildfire ravaged West Maui, Maui County’s top emergency management official, Herman Andaya, texted his secretary to ask about the status of other fires across the island.

“Still burning,” she replied.

“Wow … Lol,” Andaya texted back.

The messages were released in mid-April as part of a new state report analyzing the government’s response to the fire that ripped through Lāhainā killing more than 100 people, making it the deadliest wildfire in modern U.S. history. Documents, text messages and interviews reveal slow, poor communication between government agencies, causing hours of delay for leaders, like Andaya, to realize the gravity and extent of the crisis.

Andaya, who resigned soon after the wildfire due to broad criticism for his lack of qualifications and his agency’s decision not to sound any sirens as the fire spread, was at a training in Honolulu the day it happened. The texts show that hours after the inferno engulfed the town, Andaya didn’t know if any homes had been lost and thought only a single business had been leveled. The fire burned more than 2,000 buildings, displacing thousands of people.

To Alyssa Purcell, a Native Hawaiian archivist from Oʻahu, the lack of urgency in top officials’ response to the community’s struggles feels familiar.

“It’s a pattern,” she said. “This is not new. And I think the text messages show that there’s such a desensitization on their part to our needs that there’s nothing else that we can do at this point except go to the highest possible platforms and stages that we possibly can.”

Two days before the report came out, Purcell flew to the United Nations headquarters in New York City to speak at the U.N. Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, urging those present to support the self-determination of Native Hawaiians like herself.

“The 2023 Lāhainā wildfires exposed a systemic disregard for Indigenous rights,” said Purcell, who is a member of the Ka Lahui Hawaiʻi delegation, a group working to advance Native Hawaiian sovereignty. “Hawaiian families are struggling with disaster capitalism, where corporations and developers are using the aftermath of the fires to acquire land, develop properties, and initiate projects that are not in line with the needs of Indigenous communities or sustainable practices.”

The wildfire’s unprecedented destruction underscored the stakes of the group’s decades-old appeal for international support for Native Hawaiian self-determination. In her remarks this year, Purcell called for the U.N. to relist Hawaiʻi as a non-self-governing territory. That list includes more than a dozen territories — Guam, French Polynesia, and New Caledonia, to name a few — whose people still haven’t yet achieved self-government, either by obtaining independence or choosing to join another country.

The Hawaiian Islands were removed from the United Nations list of colonies after Hawaiʻi residents voted to become a state in 1959. But Hawai’i had only been given the option of statehood over their previous status as a U.S. territory. Unlike other island nations like Palau, Vanuatu, and Fiji, the Indigenous peoples of Hawaiʻi were never given the option of independence after the United States overthrew the Hawaiian monarchy in 1893.

“If you go back to the root of all these seemingly disparate problems, you’ll find very, very quickly that the root of all of it is the lack of self-determination,” Purcell said.

Take Lāhainā. In the decades prior to the overthrow, the coastal community was the capital of the Hawaiian Kingdom. Hawaiian royalty lived on a sandbar in the midst of an expansive fishpond along Maui’s leeward coast. But sugarcane owners in the 19th century diverted water from the wetlands to their fields, forcing many locals to abandon subsistence farming of crops like taro and breadfruit. Eventually, the fishpond was paved over for a parking lot and baseball field, and when last year’s wildfire came, the former wetland was arid and primed to burn.

The new state report on the Lāhainā wildfires found that as tourism and real estate have replaced large-scale agriculture as main economic drivers in Hawaiʻi in recent decades, landowners have left large tracts of land fallow and filled with highly flammable invasive grasses.

“The removal of active agriculture and the subsequent accumulation of highly combustible standing dead fuel on unmanaged lands is leading to more and larger fires,” the report said.

These destructive wildfires are modern and 99 percent human-caused, the report said.

“Unlike Indigenous uses of fire in continental fire-adapted ecosystems — where systemic and regular burns were used for millennia as a tool for forest health, regeneration, and swidden agriculture — the intentional use of fire in Hawaiʻi was largely limited to the clearing of lowland agricultural fields, cooking, the burning of waste, and small ceremonial practices,” the report said. “Since Hawaiian forests are less adapted to fire and are often destroyed when burned, the cultural ramifications of increased wildfires in Hawaiʻi are significant.”

Brandi Ahlo, another member of the Ka Lahui Hawaiʻi delegation to the U.N. who attended the Permanent Forum with Purcell for the first time this year, sees the Lāhainā wildfire as the inevitable consequence of Indigenous land dispossession.

“It goes back into history and the loss of water and the fact that us as Kanaka, who live on the land, aren’t able to steward our own resources,” Ahlo said. “I think bringing awareness to an international arena and forum is really important for people to see and to spotlight, because if it can happen here in Hawaiʻi, who is to say that it can’t happen to anywhere else?”

Extreme weather events like the wildfire are expected to grow more frequent as climate change accelerates. State leaders in Hawaiʻi are still trying to figure out exactly what happened in Lāhainā last year and plan to release two more reports analyzing officials’ decisions and how similar tragedies could be avoided.

The state is also trying to figure out housing options for families rendered homeless by the disaster and has cut down on the amount of food they’re giving to more than 2,200 displaced families staying in hotels. People whose homes in Lāhainā were spared still can’t drink the water that was contaminated when the fire melted pipes.

A continuing concern is the potential for private interests to capitalize on the disaster’s aftermath by seizing more water and land, both highly contested limited resources on Maui long before the fires.

In the days following the fire, the state temporarily suspended water regulations in West Maui, benefiting a major local developer who had spent years fighting with Indigenous taro farmers over access to water. On the other side of the island, the state urged a court to allow corporations to divert more water from East Maui streams. The Board of Land and Natural Resources argued that limits on water diversion — limits imposed by the court after lawsuits from Native Hawaiian taro farmers asserting their right to the water — meant that there wasn’t enough water to fight fire in central Maui.

In April, the state Supreme Court issued a ruling saying the state’s arguments were based on zero evidence and made in bad faith.

“It seems the BLNR tried to leverage the most horrific event in state history to advance its interests,” the Hawaiʻi Supreme Court ruling said.

Meanwhile, the community is still reeling emotionally from the grief of the fire’s destruction.

“When I look at the Lāhainā fires, I see cultural destruction, degradation. I see people dying. I see their homes — homes that they’ve lived on for generations — perished in a minute,” Purcell said. “And when foreigners look at the situation, when business owners look at the situation, they see opportunity.”